A Conversation with Rachel Howzell Hall

By David Corbett | April 12, 2019 |

I heard of Rachel Howzell Hall long before we actually met. I had been told by friends about her Elouise “Lou” Norton novels based in South Central Los Angeles, and found them every bit as smart, grounded, and compelling as advertised. Then I read her now famous 2015 essay, “Colored and Invisible,” where she discussed being one of the few black writers at annual mystery conferences. (This was the inspiration for a six-writer roundtable in Writer’s Digest on the issue of being a writer of color in the crime genre.)

Finally, Rachel and I met face-to-face in 2017 at the Writer’s Digest Novel Writing Conference in Pasadena, and were on a panel together where her self-effacing humor, gracious charm, and [insert superlative adjective] intelligence were impossible to ignore. I got on my knees and begged her to be my friend. (Not literally, but close.)

I also began working to get her to join us at the Book Passage Mystery Writer’s Conference in northern California, where she appeared in 2018 and was so popular with the participants we’d like her to be a permanent fixture—ahem, I mean tenured faculty member—if she’ll have us.

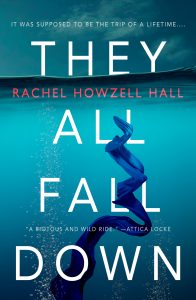

That may be hard, because she’s going to be in high demand now. Her latest novel, They All Fall Down, a standalone thriller that came out three days ago—based loosely on Agatha Chriustie’s iconic And Then There Were None—has been getting sensational reviews (“”[A] master class in strong, first-person voice”–New York Journal of Books), and it just may be that her twenty-year slog to Overnight Success may finally have paid off.

Here–let her tell you about it.

You didn’t start out as a crime-mystery writer at all. What were your first efforts in fiction, and how did that turn out for you?

No, I didn’t start out as a crime writer, but my stories always included elements of the genre—people doing bad things to each other and someone trying to understand motives. I always wrote worlds that were ‘off,’ but back then, I didn’t know to label it as ‘crime.’

In my first published novel A Quiet Storm, there’s drama, psychological suspense and a disappearance. The question that threaded the story was, ‘What happened to Matt?’ And, of course, if I wrote that story now, it would probably have the point-of-view of the detectives who, as it stands, make relatively minor appearances in the story.

But I liked the crime and mystery part of the story the most, I just didn’t know how to pull it off while also figuring out my voice. This led to a period in my career where I couldn’t sell a thing because I liked darker material, with black characters, with my odd sense of humor. Editors didn’t like it, couldn’t figure me out. Some were offended by my humor and some didn’t think my stories were ‘urban’ enough.

Rejection became as common as pigeons to me but while I flirted with the idea of quitting, I didn’t. I let those hours of dejection and depression pass and I went back to it. In the meantime, two of my rejected novels were self-published on Amazon. While they weren’t perfect, the stories are solid and should’ve sold.

But they weren’t urban enough. Heh.

When and why did you decide to turn to crime fiction?

I always wanted to write crime fiction, but I didn’t know if I could. It wasn’t until I went through some life drama of my own that I said, Why not? I decided to attempt a police procedural. If I failed, I failed.

My first intentional dip into the genre was my second self-published novel No One Knows You’re Here. And that’s where we meet Syeeda McKay, who is the best friend of Eloise “Lou” Norton, the detective protagonist of my series. Syeeda is a reporter who is following the story of a serial killer murdering women he finds along Western Avenue in Los Angeles. In real life, that serial murderer was nicknamed the Grim Sleeper. After writing that novel, I was hooked, and I began work on the first book in the Lou Norton series, Land of Shadows.

No One Knows You’re Here is where I found my voice and learned that procedurals required a different type of learning, a different type of writing. I’m still learning—and still fine-tuning my voice. And I’m still being rejected. It’s almost like Groundhog Day with having a writing career. ‘Next book’ is not a sure deal when you’re a midlist writer.

It’s a natural fit for me—I’m always drawn to figuring out why and what led to that Bad Thing. Crime scares me like it scares most people—but I need to know. Crime also has structure—and I like structure. There’s a body—that person got there, someone needs to figure out how and why that body is there and what the repercussions are now that this Bad Thing has happened. Crime stories have romance, suspense, fantasy, sci-fi… There is freedom in crime fiction, and I didn’t want to be pigeonholed in my creativity—there are so many stories to tell.

What inspired you to write an iconic African-American woman detective protagonist? What did you see as the unique challenges from a writing perspective on bringing her to life on the page?

I wanted a new perspective. When I made a determination to write crime, I read everything I could. None of those books talked about the part of Los Angeles where I lived or featured a young black woman like me. I wanted to write those stories, and I wanted to tell readers about events that happened to my friends and me in our part of the city. I wanted a character who was accessible, someone who understood the city and knew its history.

All writers face obstacles, but African-American women writers face unique ones. What were the biggest hurdles you had to overcome as your career advanced?

The biggest obstacle is that we don’t see ourselves. Everyone learns from example. For the longest time, there were no leading black characters in mystery and crime. Alice and Toni and Zora—they wrote important stories, but not the ones I wanted to write. Octavia was close but she was horror science-fiction. This field was white and male or female and cozy with accidental detectives solving crimes in between knitting circles or baking cupcakes.

I came to crime fiction as a first-hand observer, as someone directly affected by the results. Less than six degrees of separation lay between me and those who were either victims or perpetrators.

Really, we are now in a world where for some, weed is okay–Miley Cyrus’s mom was photographed standing before an open safe filled with bags of weed. How many black and brown men are in jail for the same thing?

So. The culture surrounding this genre was an obstacle. Even now, I hold my tongue and roll my eyes as I listen to people joke sometimes about murder—being punny about death (and I’m not saying that you can’t be humorous especially since editors didn’t get my humor. No, I mean, I have issues with treating the dead disrespectfully). There is gallows humor and there’s disregard and making light of the worst thing that can happen.

And!

There are only so many stories in the world but it’s how you tell them and who your leads are. There were editors who saw nothing special about Lou Norton. Oh, just another detective story. That may be true for that story, but I think overall, I think Lou’s story is different. Her relationships with her colleagues, with her family and friends, even with the victims and perps are different because of who she is, what she grew up with. Yes, the detective story may be a trope but when it’s a person of color, they bring different backgrounds, different ways of interaction with the community. My experience as a black woman in Los Angeles is totally different than Michael Connelly’s, and as a result Lou Norton is not Harry Bosch. And that’s a wonderful thing.

What prompted your decision to move away from a hard-boiled detective series and write not just a standalone, but a standalone inspired by perhaps one of the least hard-boiled—and most revered—writers in the genre, Agatha Christie?

After writing two Lou Norton novels, I just wanted to do something a little different. The story has been on my mind for a long time and after I had a set of four Lou Norton novels under my belt the moment arrived when I could actually write it. The idea of sin, especially as a crime writer, is always on my mind. Agatha Christie’s story And Then There Were None is one of the greatest stories about sin and punishment.

Did you feel any particular need to demonstrate your range as a writer, i.e., to prove you could not be easily pigeonholed? Or were you simply hoping something totally different would lift your profile?

Just like I read almost everything, I want to write those stories that appeal to me. This one story, a thriller, just happened to be that. I couldn’t fit this story into the Lou Norton universe—it would’ve been too much like the movie Se7en. I wrote They All Fall Down because I wanted to tell the story—whether it sold or not, I didn’t care. It was just in me and needed to come out. I was blessed that my editor also loved it and wanted to publish it. Sometimes, that’s when your best work comes out—when you are writing it for you and no one else. I wanted to see a black woman leading a story that is always thought of as a very white, very European story.

We taught a class on character together at last year’s Book Passage Mystery Conference, and you had an amazing exercise that used random prompts to get students to think outside the box. Could you let our readers know about that exercise, and explain why you find it so useful?

I learned this exercise from author Jo Scott-Coe who was teaching about the power of juxtaposition. It challenges writers to take one random thing and another random thing and write a story that ties these two random things together. Ultimately, the exercise trains the writer’s brain to make connections when there is no obvious connection. I found it useful when Jo first shared it and I’ve been spreading the word ever since. That is our superpower as writers, especially mystery and crime writers—making connections. Also, a superpower: taking something mundane and making it special, making it ours, making it unexpected. This exercise helps you create ideas that readers haven’t seen.

You also had students tell the class their story ideas, after which you grilled them on: Why does it matter? Why should I care? What’s the value of that exercise, and how did you come about creating it?

Yes, this exercise is one that I do all the time with my own writing. It wasn’t until last year when I started teaching writing that it actually became an exercise to share with other writers. I think every writer should ask these questions when striking out to write something. It takes a lot of effort to write stories and if you don’t care about it, why should anyone else? If you are not the expert on this story’s subject, why should you write it? This exercise saves time. There was a story I was writing earlier this year, and after putting a decent amount of time into it I began to realize I didn’t care about the characters or what was happening to them. And so I asked myself, why am I writing this? I stopped writing at that point and went back to figure out how to make this a story something that I cared about with characters that fascinated me.

With the understanding that Rachel is now on her promotional tour for the new novel, and may not be able to respond promptly, is there anything you’d like to ask her? I imagine a great many of you have struggled or are struggling in a way that resonates with Rachel’s story. Does her success offer promise?

Learn more about Rachel and her books on her website, and by following her on Twitter and Facebook.

Whoa. This is interview offers the I-trifecta: Illumination, Instruction, and (most of all) Inspiration!

Thank you, David and Rachel, for the perfect fuel for my writing weekend.

And thank YOU for reading!

Best,

Rachel HH

I identify with her having flirted with the idea of quitting and her later (liberating, I imagine) sense of wanting to tell a story, whether it sold or not. And yes, her success offers promise!

Can’t wait to read the book! Thanks, David, for the interview.

Hey, Mary.

It gets soooo hard and there are soooo many things to do on that list that can distract you, that are finite and you’re DONE. Writing is not like that. Hope my story helps!

Cheers,

Rachel HH

What a wonderful interview. I love the Groundhog Day analogy to getting it right. All the best as you go forward Rachel.

Thanks so much, Vijaya!

One day, we’ll ALL get it right, right?

RHH

“…her twenty-year slog to Overnight Success” — oh, so inspiring! The time is worth it! Congratulations, Rachel. I look forward to reading They All Fall Down.

Thanks so much, Anna!

Sometimes, it’s hard to believe that so much time has passed! But time, like spaghetti, makes writer richer and more interesting.

Best,

Rachel

There seems to be a mini spate of these And Then There Were None updates coming out right now. The Hunting Party by Lucy Foley appears to be another.

You’re right, David!

Dame Christie’s story still resonates after all this time.

It’s how we all interpret that story is the kicker!

Hope you give They All Fall Down a try!

Best,

Rachel HH

A thriller-mystery with strong first person voice? Yes! I have to read that.

Yes, please! Thanks, Augustina!

RHH

Hello Rachel.

Any writer David Corbett admires is someone I will have to read. But I have a question. We all know how many writers have published variations on the theme of this or that Jane Austen book. Do you worry that some will see what you’re doing as driven as much by marketing as by creative inspiration? Linking your thriller to a well-known Agatha Christie title has to please your publisher’s marketing department. I ask this question of someone I’m convinced has been through the twenty-year school of hard knocks, and who fully deserves her “overnight success.” I’m sincerely interested in your thoughts on this.