Sinking Into The Bog

By David Corbett | March 8, 2019 |

In my last post (“Inspired to Emulation—or Preparing to Jump“), I talked about The Rule of No Rules, and how reading other writers you admire will provide the best writing advice you will ever receive.

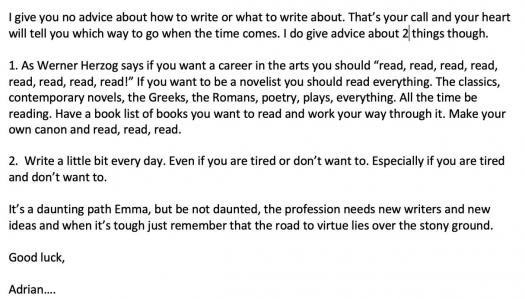

Not long after the post went up, one of my favorite novelists, Adrian McKinty—who writes brilliantly about Northern Ireland during the Troubles from the perspective of a Catholic detective serving in the overwhelmingly Protestant Royal Ulster Constabulary—posted the following letter on Twitter. He composed it to an aspiring author who had asked his advice on this whole writing business. This is what Adrian wrote in response (the recipient’s name has been removed for the sake of privacy ):

I’m tempted to end this blog post here, because I couldn’t possibly say anything as perfect, but that would be cheating, or lazy, or both. So instead, I’m going to talk a little about my writing process, and in so doing I ironically intend to prove that Adrian is absolutely right—there are no rules. (Incidentally — for more on Adrian and his truly wonderful books, visit his blog The Psychopathology of Everyday Life.)

I’m currently writing a new novel, and for the sake of this post have been taking note of my revision process, which otherwise would go largely unanalyzed. I make no assertions that my way is the right way—in fact, I would like to begin with a contrarian point, that my way actually is slow, laborious, and not suitable for “mainstream” writers obliged to crank out one or more books a year. I will leave guidance on that front to those entitled to provide it. My way is simply my way, and I hope by discussing it I might help you shed light on your own, for better and/or worse.

Searching for a phrase that might describe my way of revising, I first came up with “descending into the text,” but that seemed so utterly hokey, so sniffily pompous, I discarded it immediately.

Instead, deferring to my recent research on all-things-Ireland, and hoping for a bit of ironic wit to cut through the humbug, I settled on the title above. It’s suggestive of a process of discovering something already there on the page, buried beneath some obscuring element, waiting to be unearthed. Although that does indeed resonate with some of what I mean here, something very different is at play as well. Creation, not just discovery, figures in.

What I discover as I’m writing a given scene or chapter is that the first couple of drafts only descend so far into the emotional, dramatic, and experiential truth of the situation. I sometimes describe the precess as working out a preliminary sketch then gradually, slowly, layering on the color.

Or think of it this way: I get the furniture arranged, I invite everyone in, and listen to the first things that pop into their minds (and out of their mouths) given my initial sense of where things need to go.

This will usually occupy me for a day or two. Often I will tinker with this or that, tightening the prose, trimming away the excess, eliminating repetition, correcting mistakes. Fiddling. Mucking about. Getting acquainted with the material.

Then I descend a little further. I often need time off—overnight will do, usually—to let my unconscious prowl around the situation I’ve invented, to notice what my conscious writer self has overlooked due to being preoccupied with word choice, sentence structure, punctuation, and so on. (William James was referring to this back and forth between conscious and unconscious effort with his bon mot: “We learn to ski in the summer, and learn to swim in the winter.”)

I notice that my characters are, as yet, largely functional—they’re playing their roles, not acting like real people in the situation with quirks, tics, contradictions, dual agendas, bad habits, emotional blind spots, and so on. I need to liberate them from what I want them to do and simply let them behave.

Step one, I imagine their appearance and physical nature more specifically, and look for what I missed so far—the torn pocket on a shirt, mustard stain on a tie, worn heels on the shoes, hair dye, a hand tremor, cologne or perfume. This almost always brings me closer to the character’s emotional and psychological specficity as well.

Step Two, I remind myself of each character’s Objective, Obstacle, and Action: what she wants in the scene, what stands in her way, what she does to overcome the obstacle to achieve her goal. I clarify and intensify the tension, and make sure I’m revealing through conflict, not straight narration.

Due to Donald “Master Don” Maass’s expert advice, I now also ask myself how each character hopes to feel by the end of the scene, and what happens to that hope, that feeling, given what happens. This helps me not only understand each character better, but to distinguish among them—for example, if I have friends or siblings or co-workers in the scene, this is usually where I begin to separate them more clearly in my mind.

Once I have that in hand, if the scene still feels unfinished, I take each character’s perspective and run through the scene from their point of view, then do so with each of the other characters. I listen for what each character would really say given what just happened. each character’s distinct rhythms, their idiosyncratic word choice (more on that below)—most importantly, I imagine more deeply what they would feel and what they would do, letting the dialogue, if any, arise from that.

On the issue of word choice specific to each character: One of the greatest techniques I ever learned in this regard I gernered from Joshua Mohr, another wonderful writer. He suggested setting up a dialogue grid, with each character’s specific or idiosyncratic verbal expressions, from certain words they “hit” particular hard or often, to regional dialect, to favorite curse words, to syntactical peculiarities—e.g., the subjectless sentence (“Going to the dance tongiht?”), the serial interrogatory (“Mrs. Hornby? You know the report you wanted me to write? About Chaucer?”)

If I’m still feeling like I’m not quite there, I remind myself how this scene fits into each character’s general Yearning—their dream of life: the kind of person they want to be, the way of life they hope to live. This scene is a moment in that pursuit—where does that moment fit in the general outline provided by the story, and the story within their lives. If I’ve associated the Yearning with an image, a symbol, or a piece of music, how does that get reflected here?

Similarly, what is holding them back from fulfilling their Yearning—what wounds, weaknesses, limitations, moral flaws are undermining their pursuit of their dream of life. How is all that reflected here?

Sometimes this takes deliberate effort, other times it’s an intuitive plunge into the scene. It may take one day, it may take three—but if I’m not getting it right by then, it’s time to move on.

As I continue into the story, my unconscious will continue providing me little insights—a change in an action, a line of dialogue, a description—and I’ll jot them down and slip them in where they fit, or make notes to myself to return to the scene and write the change in.

This sort of revising-as-I-go is contrary to the advice of many writers, who save this sort of revision for a second pass after they “have the story down.” But I don’t feel I’ve truly got the story down until I do this sort of sinking into each scene. Until then I’m just skimming the surface of events—and is that really the story?

This deeper exploration of each scene often feels like discovery, as though I’m finding what was already there but wasn’t yet aware of. And yet it is also creation, obviously, because I am inventng new details, adding touches I come up with on the fly. The test of truth to any created bit, however, is if it serves the story, rather than feeling jammed in or slapped on for effect. So in truth it is more of a back and forth between creation and discovery, and the bog I’m sinking into is my imagination.

Regardless, this effort typically also prompts me to go to my outline and make changes in the overall story—usually to upcoming scenes, but on occasion for already written scenes as well.

I know this all sounds laborious, and as already noted, it’s time-consuming. I can’t say I recommend it, and I envy those who can work well more rapidly. I’ve tried just plowing ahead, however, hoping to get a “lousy first draft.” Sooner or later it just feels wrong, like I’ve taken a wrong step, or have sold short the real possibilities in the story. I’ve ultimately had to accept that this is simply my process, and as I often tell my students, one of the most important things you will learn as a writer is how you work and coming to trust that.

Now, of course, we all develop bad habits, and shouldn’t allow them to undermine our work in the name of “owning our process.” But in the inevitable calculation of what is the best use of your time, you need to gauge for yourself whether that time is better spent moving ahead with your current way of doing things or better spent breaking down those bad habits, learning new ones, and suffering the inevitable struggles any such change in methods will entail. (Those who have taken the plunge into Scrivener have no doubt insights to share on this trade-off.)

Regardless, we once again return to The Rule of No Rules. You have to find your own way into and out of the bog, as both Adrian and I have advised. Sadly, there are no guarantees—or, as Adrian advised his fledling writer, “It’s just the nature of the beast.” There are simply the stories only you can tell, and that will have to suffice, as it always has.

What parts of your writing process would you change if you knew how, or could risk the readjustment time required? What do you think of Adrian’s advice to his fledgling writer—do you agree? Disagree? Something in between?

Thanks for this. Sadly, my method is much the same as yours. When my nearest and dearest ask me what chapter I’m on, I mumble, “four”. Surely I should be farther along. But I can’t rush it. If I know a word, a sentence, a scene, isn’t right or I can’t feel or see it then it’s impossible for me to move on.

I’ve tried other methods to speed up the writing process but end right back in the same place, using the method that works for me. The novel will be done when it’s done.

I agree with Adrian’s advice. My bedside table is groaning with books to be read. With a busy home business, I write as little or as much as I can every day. This morning I was up at 5:00 am for a bit of quiet writing time before the household begins to hum.

Thanks again, David. You’ve given me an encouraging start to my day.

Few things make me happier than to know I’ve lent encouragement to someone hoping to write. Thanks, Linnea, and good luck.

Hope you don’t mind my sharing this with my women’s fiction writer pals on their Facebook group. So much wisdom here, I couldn’t keep it to myself. I’m in the middle of final revisions to my first novel and doing much of the type of deep examination you’ve described. Your columns are always excellent and insightful- this one particularly so.

Mind? Christ, Maggie, I’m flattered. Share at will. So glad you found it useful.

Hey David, Since you’re all, “Come on in—the bog mud is fine!” I’ll dive in, head-first and heedless.

First, having ancient Germanic tribespeople for characters, I love the metaphor. I think I’ve told you before that my primary characters are based on the Goths at the time of their initial contact with the Romans. But living among my Goths is a warrior sect, the Skolani (they’re an all-female warrior sect—yep, I haz Amazons… Don’t judge).

Since the Skolani are mostly untethered from actual history, I had a lot of fun creating their culture. A long time ago I decided that they were secretive about their dead. They never leave their dead on the battlefield. But no one else in my story-world knows what they do with them. Turns out they devote the bodies to a hidden bog, at the fringes of the realm. Their primary deities (both female) are an Artemis-esque moon goddess and an earth mother (sort of Nerthus-like, minus the wagon thing). Though the Skolani prize “heirloom swords,” particularly brave warriors who’ve died particularly valiant deaths are devoted with their weapons (sort of like retiring a great player’s number).

In contrast, my Gothic characters have a sort of cemeterial tradition, taking their dead to an “Isle of the Valiant Dead” that keeps a semi-embalmed corpse around undisturbed, with their weapons and personal futharks, for future visitation and reverence. As if a rotting corpse might offer “bragging rights” to future generations.

Sorry for the long setup. Anyway, I had a lot of time since I decided this stuff (over a decade ago) to consider it. It’s become part of “my truth.” In the process of making my work saleable, I often feel like I’ve taken my original story and dragged it to a publishing version of an “Isle for the Valiant Dead.” I’m arranging a corpse, laying the sword and shield out, positioning the futhark stick under the chin like a processing number on a mug-shot, and inviting future generations to *please row out and have a look—see? It’s not so foul-smelling!*

What I’ve since decided is that my process is more scribe than mortician. I’ve got to give it over to mother earth—to say a prayer and gladly devote what was given to my sacred bog; to let it be subsumed, where it can provide fertility to those who follow (rather than a monument to what’s naturally decrepit).

The work I’m doing right now is a “refashioning” of a story that was originally set down by a very unskilled aspirant about seven years ago (guess who!). Just this week I came to a pivotal scene, and I was so tempted to go back and reread the original text—maybe even swipe a bit of it. “It wasn’t so bad,” I tell myself. And wouldn’t the reminder be helpful? But no. It would be rearranging the corpse. Which, for me, is synonymous with writing to the market.

I remind myself that I am but a scribe. I need to disappear to the sacred bog, and wade in, to seek the green shoots and tendrils, to listen to the stories of those given over, whispering in the boughs overhead. And if it’s meant to be, yes, I may find a sturdy bone, or once-precious piece of jewelry, maybe even a treasured blade (a retired jersey). And these things will guide and inspire me, but they are for me. No one else. They would never even make a future buyer pause in the marketplace.

In other words, let it go and sink in. Tell the story. I’m on fertile, and sacred, ground. No one else will know or care… Until they do. But that’s got nothing to do with me.

And, yep, I’m full-on crackers—lost in a bog. Thanks for your wonderful piece. It makes me feel a bit less so (no indictment on you!).

“I remind myself that I am but a scribe. I need to disappear to the sacred bog, and wade in, to seek the green shoots and tendrils, to listen to the stories of those given over, whispering in the boughs overhead. And if it’s meant to be, yes, I may find a sturdy bone, or once-precious piece of jewelry, maybe even a treasured blade (a retired jersey). And these things will guide and inspire me, but they are for me. No one else. They would never even make a future buyer pause in the marketplace.”

What a wonderful way to put that, Vaughn! It seems to me that it is better to relinquish control and trust that something will emerge eventually. And let the spirit of imagination (or whatever it is) take over as you sink into the bog. After five novels and 25 years, I finally realized that trying to control the final product too rigidly as I’m writing is a way to make me hate the whole process. That’s just another form of madness, and I think I prefer yours.

HI, Vaughn:

Why would I judge you about having Amazons? I have a book on their appearance in ancient myths and hsitories that I’m enjoying right now.

Sometimes I feel like a scribe, other times I realize I’m actually adding to the message. But there is a definite sense of immersion. And yeah, once you’re done, there’a distinct feeling of returning from the Otherworld.

Onward!

Excellent addition! In my scribe scenario, I envision that I am being asked to interpret or even “enhance” the message. Definitely a calling to add my ephemeral self to the narrative. Or, as they say on all of those singing shows to the contestants: “Make it your own, Dawg.”

Sorry about the knee-jerk defensive parenthetical regarding Amazons. I’m not sure which book you’re enjoying, but Adrienne Mayor has a wonderful one (Amazons–the Lives and Legends of Warrior Women Across the Ancient World).

Great post, Dawg! Thanks again. Wishing you happy immersion.

I LOVE this post! I don’t think I’ve ever read such a profound and thorough description of the writing process. In particular, I appreciated your point about the recursive, nonlinear relationship between discovery and creation: as we become aware of what is already there, something else reveals itself that we never imagined till then. Thank you for this!

You’re more than welcome, Barbara. Thanks for the kind words.

David, after reading your excellent dive-to-the-bottom-of-the-river (and then further) cold-water plunge into writing, it’s clear: you should write my next book. I will supply plenty of Irish whiskey and massage your shoulders when you weary.

Great stuff, reminding me of the sift, gather, sift, gather nature of the process. And the Adrian letter—that covers the bases, backwards, forwards, under the surface and in the air. Sweet.

Thanks, Tom. I like that: sift, gather, sift, gather. Exactly.

David, this is a fantastic explanation of the inexplicable process we call writing. I found two particular gems that hit home, and I may have to borrow them the next time a reader asks, “where do your ideas come from?” The first describes how I feel about getting to know characters: “I need to liberate them from what I want them to do and simply let them behave.”

The second gem describes the joyous process of turning that initial spark into a story: “This deeper exploration of each scene often feels like discovery, as though I’m finding what was already there but wasn’t yet aware of.” I have never yet found a way to adequately explain that sense that I’m “learning” what happens next as I write.

I love the image of imagination as bog. Thicker than water, but still porous, if only we can find the tools to dig deep.

The only piece that doesn’t ring true for me is that quiet reference to an outline, but I’ll leave that for another day!

Thanks for writing this. When I’m pining for a more efficient workflow, it helps to remember others slogging away, digging down into their own stories.

Outline? Who said outline?

Oops. Busted.

But I think, as my remarks indicate, the outline is as much a work in progress as the book itself. Has to be, if you’re going to write honestly.

Thanks for the kind remarks, Carol.

Brilliant!! I love this post! and I totally agree with you and Adrian: Read, read, read! I too am “slow, laborious, and not suitable for “mainstream” writers obliged to crank out one or more books a year.” But I am happy about that and have no need to amend my behavioral style; same with the William James point of back and forth between conscious and unconscious effort — revising as I go “back and forth between creation and discovery.” For whatever reason I am happy all the way through the process. Thank you so much for this wonderful post and sharing your style.

Thank you, Luna. here’s hoping your happiness survives publication! (It doesn’t always turn out the way one had hoped–though you’re probably already aware of that.)

I am not unhappy with the sales, and critical acclaim of the first novel, The Sleeping Serpent. But I also don’t have any attachment to the outcome. I love to write, don’t like to market and spend my time between reading and writing with a daily break of vigorous exercise and the enjoyment of nature when possible. So, second book has benefited from a good learning curve from the first. I have been reading Rachel Cusk, Virginia Woolfe, James Salter, Paul Auster, George Saunders, more Murakami and McEwan (of course) and Elizabeth Strout who I just met this week! What a delight! I always enjoy your insightful posts

David, this may be one of my favorite Writer Unboxed posts ever. Thank you! You have described my writing process with almost eerie accuracy. Sometimes I’ve thought I was doing it wrong or that I somehow lacked enough imagination to envision a scene fully the first time around. But the slow layering on of detail as the scene emerges from the mist (or the bog, which is a better metaphor) is really quite magical though, as you point out, very time consuming and laborious. I often find the first attempts painful and disheartening because I am so aware of everything that isn’t right and everything I don’t know yet. Patience may be the writer’s most essential quality.

Hi, S.K.:

Yeah, the first attempts are painfully inadequate, but writing is rewriting, and you can’t revise what you haven’t written. Sometimes I feel like I’m etching every word in granite with my fingernails, but I have to get something down so I can return to it and make it better.

Ah, beloeved madness!

Make that “beloved.” Oops.

Master Don weighing in here. (Master Don? Really?) I like your notion of revision as descending–by layers, using different crowbars–into a given scene. It’s accurate. It’s how I revise, too.

What you’re describing, though, and what I experience is a process that’s necessary because the first draft is written in a state of resistance. Of safety. Of caution. First drafts are too careful.

Characters (I write fiction as well, under other names) do not at first reveal themselves; or, more to the point, I am afraid to let them be real. Initially, they do what I–not they–think they should do, serving not only the plot but my sense of what good fiction reads like.

However, plot is a dictator not a liberator and while I am in no way against strong story events, I also know that novels feel real and become compelling when characters act as spontaneously and surprisingly as actual people do. You have written often, Sir David, of “plot puppets” and I find in first drafts that is something like what I create.

At this stage of my career, with twenty books authored, fourteen of them novels, I ought to know better. I know perfectly well that playing it safe doesn’t work. And yet that is what I do–at first. Revision is the process not of refining the text but of clearing away my own timidity.

It’s like those home-flipping shows on TV where sledgehammers are taken to the ugly wallpapered walls and cheap bathrooms to strip the house back to its bones and make space to imagine the stunning, open-plan beauty that is really there.

In revision, I’m not so much delving as ripping out the ready-made junk I installed from Home Depot. I’m clearing away my own fears to see the human beings that are really there, and for that awareness I have you to thank. Your book, posts and comments push me to be sure that my characters are authentic.

First round’s on me.

Just for future reference, I prefer Emperor David.

That is a fascinating way of looking at it, Don. And using that analogy of revision as overcoming one’s fear, with each revision we come a little closer to that thing we fear, which is the uncertainty inherent to real creativity. Approaching the unknown but with a sense of what rings true and what doesn’t.

I think that adds an additional element to the process, which is growing increasingly aware of when you’re bullshitting yourself. When you keep a line because you love it like the darling it is, instead of remaining true to what is necessary. When you settle for plot puppets because the story just skates along–and that’s the problem, it’s all on the surface.

In the end, I keep returning to the same three virtues to not only guide my life but guide my writing: honesty, compassion, and courage. Abide by those, you’ve got your hands full–at the dinner table as well as at the desk.

P.S. Your comment also suggests another question to ask upon revisison: What am I, the writer, afraid of addressing or revealing in this scene? How can I bring that up from where it now lies buried into the light?

Yes! Absolutely. Copying that.

Don,

“Revision is the process not of refining the text but of clearing away my own timidity.”

This knowing your process is akin to David’s. He does it by the chapter and you do it, if I hear you correctly, by the book–if you know what I mean. And your humanity in carrying on with your early fearful steps to reach what you are after as a storyteller inspires me. Thanks.

David, thanks for that wonderful letter of Adrian’s. I agree with him wholeheartedly, esp. the write every day part, esp. when you don’t feel like it. Because lots of times when our defenses are down is when the magic happens.

The years of writing nonfiction have spoiled me–I want a nice, little pathway to my destination. But fiction really is cutting through the brambles, facing your fears, the dragon, the stuff of dreams (I picked up Butler’s book upon your recommendation). Holy cow! I’m returning to a more organic way of writing, similar to when I first began, trusting the process more, but now with some serious craft tools for revising. I think I understand better why I’m so good at short stories–they come in a flash and I know how to capture them. Can’t do that with novels; just pieces of them. But I’m learning, learning. Thank you for sharing your process.

I think you make a marvelous point, Vijaya. What we’re really after, beyond the years of struggle, is to return to the freedom of play, of untethered creativity, which we can only do once we trust that we have the revision skills necessary to clean up after ourselves. We know we can make it right. But first, trust the descent into the trance and just go.

Thanks for a brilliant post, David. I love the metaphor of the bog!

That insight about knowing our characters’ hopes in every scene is one I’ll file away for future use. And Adrian McKinty’s advice to write everyday, even when you don’t feel like it, ESPECIALLY when you don’t feel like it.

Perfect advice for my life right now.

David, what a juicy read! I’m one of those Scrivener users and writing my fifth book using the program. Still discovering best Scrivener ways to frame the story’s basic structure, arrange the scenes I envision using, pull in and hold my historical research, and manage all those details, loose ideas, reminders to remember and so on and so on. It’s marvelous! I find if I get too tied up or invested in one scene it’s like I’m trying to force it to ripen before it’s time. So I suppose I’m more of an inbetweener. Using the program I can dip in and out comfortably. Now all that being said, I write a middle-grade mystery series. My books are only 80,000 words. One day I’ll see how a lengthier novel, with more complex characters, shifts my process…but I’m excited about that too!

I’ve only written two novels so far, and I’m still trying to figure out what works for me. The last one I’ve kind of become “mired in the bog.” With the first story I made several passes looking for specific things. When I started trying to do the same with the second novel I kind of stalled–but having multiple passes is so helpful. I think the difference for me is going to be doing the passes, but not letting myself get stuck in the decision making so that all progress halts. I’m looking forward to starting a new novel soon, and I’m going to give it a try.

It also seems like I edit differently when I write short stories, but I’m planning on trying the several quick-decision making passes method with the short story I’ve started. Kind of like a trial run to the full novel. :)

Thanks for sharing your process, because it helps to hear what works for other people and to see what I might be missing in any given story. And I loved the letter, so thanks for sharing it, too!

Great post, David. It explains one of the biggest problems I have with my writing: rushing through a story, fretting that I’m wasting too much time, instead of digging into scenes and characters to decide what I want them to do and where I want them to take the story. It’s the difference between tossing a frozen dinner in the microwave (and being disappointed with what comes out) and taking the time to prepare a meal and appreciate the process — and the results. Thanks!

I happen to love “descending into the text” – !

If I could change something, it would be that I wish I were more structured. I just go with it – follow the character(s) around to see what they will do. Oh, it’s definitely not Mainstream writing! It’s all character-driven. Oh to write more plotty!

I agree about the stop listening to so many rules and so much advice.

Very nice article!

David, your post reassures me, who also feels like I write in such an inefficient way. Why does it take me so long? Why do I write in such a non-linear way? Sinking into the bog is a good image. That’s how to go deeper, but certainly not faster.

David,

This is a wonderful reveal of a writer’s process . . . not to be confused with what should BE another writer’s process. Thank you. Though it is yours, it encourages us to find ours. What strikes me most about the post is the intimacy of it. Letting us see how you have found and built a logical way to use your creativity. As I read, I felt the momentum of the “sinking,” how it was working, knowing that the result would be anything but below ground, anything but mired in a bog. And I’ll bet you do too, with pleasure, as your characters sprout flesh to the bones you provide them, and inject feeling into flesh, and craft independence from feeling. . . with results similar to those of Pinocchio becoming a real boy. Which probably elevates the work into the realm of wordless insight that inspired the story to begin with. In a flash we see our stories. And then the work begins.

I suspect you are able to be disciplined in your writing this way—not too tight, not too loose—because you are not a pantser (you mention working from an outline.) But it seems some of the steps you use draw from the pantser school. Letting your characters speak their minds, for example. I wonder if this hybridization may access the magic whereby wood becomes flesh.

I work in a similar way, though I think of it more as circling, back and back, not charging for the end of the draft, but for authenticity as I go. I know where the story is heading, but it’s not prescribed in minute steps, and I allow for the possibility in the early draft that it may not ultimately end up where I thought it would. The two main characters in my current novel started expressing irritation that there was not a third protagonist to humiliate them properly, to call them out on their narrow way of viewing the world. Down deep, they wanted better for themselves. And voila! He gave the story dimensions of depth I couldn’t have thought my way into.

Glad you are feeling better.

Thank you!!

David, besides getting exposure to books I might not otherwise read, the thing I most appreciate about WU Dissections are the abundance of rule-avoiders among breakout novelists. And the thing is, we’re picking books that are both commercial and critical successes. I find great comfort in the lack of writerly perfection.

Speaking of the Dissection group, there’s still time to prepare for April 11th, when we’ll be analyzing Katherine Arden’s THE BEAR AND THE NIGHTINGALE. You, or anyone other WUers, are more than welcome to join us.

Thanks to one and all for all the kind remarks. It seems I touched a chord, and a rather lovely one at that. I’m glad this community offers us this medium to interact, exchange thoughts, compare methods, and ponder how we might next approach that greatest of all villains, the empty page.