Tips for Complex Historical Research

By Guest | March 7, 2019 |

Please welcome back Alma Katsu to Writer Unboxed today! Alma is the award-winning author of THE HUNGER, a reimagining of the story of the Donner Party and one that Stephen King has called “Deeply, deeply disturbing.”

Additionally, THE HUNGER was on NPR’s list of 100 favorite horror stories, was named one of the best books of 2018 by Barnes & Noble and Amazon, and was just named a Bram Stoker Award finalist! It released in paperback two days ago, on March 5th.

Her debut novel, THE TAKER, was one of Booklist’s Top Ten Debut Novels of 2011.

Learn more about Alma on her website and by following her on Twitter.

Tips for Complex Historical Research

Is America afraid of doing research?

That’s the question I had to ask after touring for release of The Hunger, a reimagining of the story of the Donner Party with a horror twist. The question I was asked the most at events, hands down, was how did I manage the research for the book?

Why this horrified fascination for research? Were we all scarred writing research papers in high school?

I admit that the amount of research required for The Hunger was pretty daunting, but that’s because it wasn’t merely set in a historic period, it was about a specific and well-known historical event. It had to follow the actual route and timeline, and it also had to cover a huge cast of characters (there were roughly one hundred people in the wagon party, including children). I joke that there are, easily, ten thousand facts tucked throughout the book and that might be a conservative estimate.

Luckily, I was prepared: I’ve been a professional researcher for over 30 years. I’ve found it’s well-suited for historical fiction, maybe even more so than historians. The difference between historians and researchers is that researchers are trained to sift through information surrounding a subject quickly and efficiently in order to make logical sense of it and reduce it to its essential elements, while retaining integrity of all the facts.

Based on questions I’ve been asked, the two main problem areas for most writers seem to be: (1) How do you know when to stop gathering information (“help me, I can’t stop researching”) and (2) How do you organize and manage your notes? I firmly believe you don’t have to read everything that was ever written on your subject before you can start writing. However, you do need to have a sense of what you need to know and the discipline to trust your judgment.

A few tips to bear in mind:

1. Limit yourself to two primary reference works. There are dozens of books, non-fiction and fiction, about the Donner Party. It would be easy to become bogged down (if not paralyzed) trying to consult them all, but that would result in a lot of redundancy. Do a quick look into which are the best references for your purposes (skim reviews, see which ones other researchers recommend), are readily available, and then ignore the siren song of those spurned volumes. You can always do spot research on specific problems as you write.

2. Read through those two books and take copious notes, but the main thing I’ve found that adds magic to a book, at this stage, is to look out for quirky details on which you can build a character or sub-plot. This may not seem like a mind-blowing tip, and of course what makes for great material is subjective, but it surprises me how many opportunities other writers seem to have passed up. Almost all the really bizarre moments in The Hunger are based on things that actually happened and, I think, give the novel the feeling of genuineness.One example: early in The Hunger, we hear of Ash Hollow, an abandoned hut that is used by settlers on the Oregon Trail to leave letters for east-bound travelers to carry back to civilization. This actually happened in real life, almost inconceivable to us today. As soon as I read it, I knew I wanted to use it in the book, and it ended up giving me an opportunity to introduce something unexpected and eerie by marrying something supernatural to this weird but true fact.

3. Use estimative probability when evaluating online sources. Reputable sources are easy to identify; it’s the ones that look home-grown that can give you trouble. While researching The Hunger, I’d find the occasional tantalizing fact, something I couldn’t find anywhere else, buried in an amateur historian/genealogist’s blog. Do you use the fact or not? In my day job, we assign an estimate of probability: is it probable, possible, or unlikely to be true? Probable, if everything else is in keeping with the established record; unlikely if little else tracks; and possible for all points in between. Work up your own metrics for those three values and then apply them whenever the question arises.

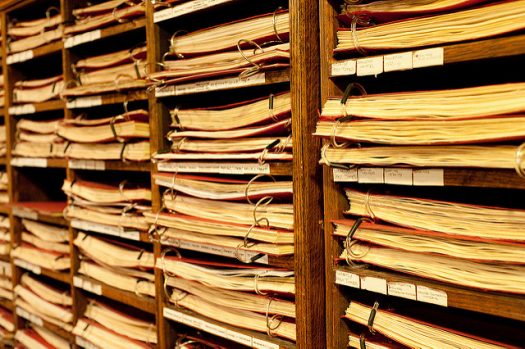

4. Don’t keep notes on paper or index cards. I realize this is going to going to be controversial, but I believe you should keep all your notes electronically. That way, you can easily search on them and move stuff around if you find some great tidbit that needs to be squeezed between existing notes. No more post-it notes or loose pages stuffed into notebooks, or losing ideas you wanted to work into the story.

Excel is my preference for note taking: You can keep separate sheets in one workbook for characters (saving multiple aspects of the character, such as hair and eye color, pertinent background, etc., in the columns), background notes, and as many timelines as you need to keep track of. It’s better suited to juggling a complex assortment of facts than notebooks, which tend to force you to think linearly.

Excel can also make it easier to keep track of revisions. I create a worksheet each time the manuscript goes through a major revision. There were multiple substantial revisions for The Hunger, with lots of action cut or replaced, and I used a spreadsheet to keep track, per chapter, of main plot points, POV, date, and location.

Though far from exhaustive, I hope these few tips inspire you to roll up your sleeves and dive into that research chore you’ve been putting off.

If you have a favorite research tip, please add it in the comments and share your knowledge and experience.

Great advice. I particularly like the idea of two main resources. I also write historical fiction and can get lost in details!

Thanks!

I just told her the same thing on Twitter. Now there’s less of a chance they’ll find my body under a fallen stack of paperwork.

Tip number two is actually my favorite part of writing. I love finding the odd but true historical fact or bizarre coincidence that perfectly aligns with my plot and characters. It hits my brain’s reward center like nothing else when I’m writing. Great tips!

Thank you so much! Glad to hear this is helpful.

I write historical/historical fantasy and some of my favorite sources are contemporary ones. Once I’ve got those main sources lined up, I often go digging into primary sources: trail diaries, reports–even contemporary novels–because those often reveal details of the era that history books miss. I also keep electronic notes, though I use word with the headings function for different topics.

All great tips! I admit, I usually avoid novels for the regular fears, but you’re right, we shouldn’t rule them out, out of hand.

Terrific advice, Alma. The Hunger was unputdownable for me I think because you made the entire experience come alive in a way that felt absolutely authentic. Wonderful column.

Thanks so much for the kind words.

Two main sources are great advice. In my present research, I’m trying to find justification for a sequence stating, not hinting, that FDR KNEW that the Japanese Imperial Navy would be attacking Pearl Harbor. (My own opinion, after a lifetime of reading and thought is that he did.) In looking for such information, I’m waaayyy beyond two sources. But I’m glad for your advice about sticking to two main sources.

Yes, there are going to be those instances where you have to chase that rabbit down that hole, aren’t there? Mine are usually far more mundane. Good luck!

I worked as a professional research historian at Cal State University for many years, and I strongly disagree with only using 2 main resources. I’ve published several nonfiction history books and recently published a historical novel set during WW1. Many of the older books I used as research sources conflicted with recently researched and published nonfiction books, and there are many different opinions woven into those books. One of the basic tenets of historical research is using primary sources when possible, and then comparing the biases of those who wrote them. As such, I had to use numerous books, taking copious notes, and then evaluating the writers and their sources to research my novel. It’s a difficult task, but I want my books to be based on the best research possible. Two books simply isn’t enough in many instances.

Colleen, I couldn’t agree more. As a history major now working on a narrative nonfiction piece firmly grounded in research (the fiction will have to wait, but some of it is also based in earlier times), I am committed to the principle of distinguishing between the opinions of different historians, and of using primary sources (actual documents, not interpretations) as much as possible. Two sources, as you say, are not early enough. The historians I know are all meticulous researchers.

I think you both have hit on the main difference between a historian’s approach and a researcher’s approach. I advocate against people going overboard on research when, in most cases, it’s not justified. It depends entirely on the project, of course, but I’ve found too many times writers experience research paralysis and then have a tough time figuring out which facts should go in the book, etc. Or worse, you end up with this mess of exposition and facts crammed in that end of bogging down the story, or derailing it entirely. For fiction, the research should serve the story, not the other way around. I realized going in that this would be an unpopular opinion with some, but 35 years of researching for government and think tanks, and four books later with lots of historical content, and I stand by my experience.

Nonfiction, obviously, is an entirely different situation from fiction.

And, as someone who has led teams of researchers, I’ve had plenty of times when I’ve had to kick someone’s *ss to get them out of research paralysis. To each their own but recognizing when you have a problem is half the battle. I’m not saying you have a problem, but plenty of people tell me they do. This is permission not to wrap yourself around the axel.

I love research! Probably as much (possibly more) than the writing. The big issue is time. The types of stuff I like to write are very research intensive. But because it IS so research intensive I do get paralyzed. So one of the tips you mention is one I need to work on–learning to do research in a more efficient manner. That’s hard to learn to do when you LOVE disappearing down a rabbit hole for hours on end. Too little time for the fun stuff. 8-)

Thank you for the advice on research. But, really, I just want to read the book.

I hope you enjoy it!

Great ideas about using Excel. OneStopforWRiters also has great resources for that too. Thanks for sharing!

My research period is early 20th century, so historical photographs can be time-saving and invaluable in establishing details of setting, dress, dining, transportation, and communication.

I’m not afraid of research– I’m terrified!

I have an idea for a historical novel that I’ve been kicking around for a couple of years now, but it’s so much easier to knock out a contemporary novel with imaginary characters. Maybe one day I will get over this fear and get this book out of my head and onto the page!

Thanks for the excellent reminder that there can be too much research. I discovered that with my first historical novel (it’ll debut in 2020!). One of the big revision passes for my agent was making the novel less dense as far as historical detail went. I simply knew too much and couldn’t see the forest for the trees anymore. And that in a book where none of the characters were real, all fictional, but in a real historical context.

One of the biggest challenges for me is knowing what I need to know for the book. So I research wide at first just to find those tidbits that spark excitement in me. Then I narrow down to the details I think I’ll need. Since I do 20th century history, I lean heavily on photos, documentary film and oral histories. If there are people still alive who experienced the period I’m writing about, I talk to some to get private impressions that haven’t been printed anywhere else.