Critiquing for Shades of Gray

By Nancy Johnson | December 4, 2018 |

When Erin Bartels and I agreed to be critique partners, we knew we had similar writing sensibilities and a commitment to telling emotionally resonant stories. Interestingly, both of our debut novels explore race in America. However, as much as we are alike, we approach the world and our characters from vastly different perspectives: She’s white. I’m black.

When Erin Bartels and I agreed to be critique partners, we knew we had similar writing sensibilities and a commitment to telling emotionally resonant stories. Interestingly, both of our debut novels explore race in America. However, as much as we are alike, we approach the world and our characters from vastly different perspectives: She’s white. I’m black.

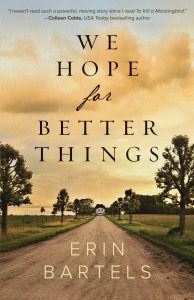

Erin’s novel, We Hope for Better Things, which releases in January, received a starred review from Publishers Weekly. It takes a compelling journey through the intertwined lives of three women—from the volatile streets of 1960s Detroit to the Underground Railroad during the Civil War—to uncover the past, confront the seeds of hatred, and discover where love goes to hide.

I’m revising my first novel, The Kindest Lie, which tells the story of a black woman engineer trying to reconnect with her biological son. She befriends a poor, 11-year-old white boy. Their mutual need for family collides in one fateful night, exposing the fault lines of race and class in a dying Indiana factory town.

In anticipation of the release of Erin’s debut, we talked about the critique process and how we navigated the weighty, and often uncomfortable, topic of race as we provided our feedback.

Nancy Johnson: I had this huge fear all along about how I would tackle my predominantly black cast of characters. You may think that’s absurd since I’m black. But that’s the thing. I desperately wanted to represent the best of my community since we’re often perceived negatively in literature and media. Then I began to worry that I was over-correcting and villainizing my white characters. You flagged my blind spot on how I portrayed white parents.

Erin Bartels: Yes, I did notice when I read that, while black parents in your book were portrayed as fully three-dimensional, with both good qualities and bad, there really didn’t seem to be any “good” white parents. They were neglectful, inept, or abusive and seemed disinterested in their kids. I flagged it more as an observation than a critique. There are a lot of bad parents out there. But I think what I liked about your black parents was that even if at first Mama seemed harsh toward Ruth, as I read I could see why; I could see where she was coming from and how she thought that it was the best thing to do at the time. She was understandable to the reader.

I think it’s natural for us to make those characters we feel we know better more three-dimensional. One of the things I worried about in We Hope for Better Things was that some of my black characters would feel two-dimensional, that they would seem like they were only there to serve the storyline I had set up. Especially characters in the most historical of my three storylines, the 1860s. I just have zero real idea what life was like for them and research can only take you so far.

And though I’d had three black friends read the book before you did, I was worried that they weren’t saying everything that was on their minds as they read it. You mentioned that you struggled to know what to say and what not to say in your critique.

NJ: Yes! As I was writing my critique notes for you, I kept deleting the difficult parts. I agonized over whether to bring up the problematic white savior tropes. Still, it had to be said. In both the Civil War era and the 1960s, black people didn’t have much agency at all. That’s why I was sensitive to the depiction of white folks rescuing hapless blacks. Also, I wanted to see the black characters fleshed out more, fully realized as characters and not just a device to serve the interests of good white people in the narrative. What were your initial thoughts when you read what I had to say?

EB: Honestly, I was so relieved when you pointed out problems. It’s like when someone points out that your fly is down, and you think, “How long has it been like that and no one said anything?!” I knew intrinsically that I hadn’t gotten everything right—I know I still haven’t gotten everything right—but I needed someone to show me exactly what I’d gotten wrong and, more importantly, how I could improve. And if someone who cares about you can’t be honest with you, you know who will? Reviewers. They’ll be brutally honest. So, I’m glad that you said what was on your mind and let me figure out how to improve the story. I’m not sure I was quite as helpful to you because the main white character in your book is a young boy in a lower socioeconomic rung of society, something neither of us has had experience with.

EB: Honestly, I was so relieved when you pointed out problems. It’s like when someone points out that your fly is down, and you think, “How long has it been like that and no one said anything?!” I knew intrinsically that I hadn’t gotten everything right—I know I still haven’t gotten everything right—but I needed someone to show me exactly what I’d gotten wrong and, more importantly, how I could improve. And if someone who cares about you can’t be honest with you, you know who will? Reviewers. They’ll be brutally honest. So, I’m glad that you said what was on your mind and let me figure out how to improve the story. I’m not sure I was quite as helpful to you because the main white character in your book is a young boy in a lower socioeconomic rung of society, something neither of us has had experience with.

NJ: Indeed. One of my point of view characters is an 11-year-old white boy. I’ve been 11, but I’ve never been white or a boy. Often, white writers ask me for advice about writing black characters. They’re terrified of getting it wrong. While I’ve existed in white spaces my entire life, I didn’t know if I could pull off getting inside the head of Midnight, the white boy in my novel.

EB: What I find so funny about that, Nancy, is that when I read your story, I felt that Midnight was so vividly and lovingly drawn. His motivations were clear and comprehensible. His fears were real. His mistakes were felt deeply. He felt more real to me than Ruth, your black adult female protagonist, and I don’t think their races had much of anything to do with it. You and I have talked about how we both feel more comfortable and perhaps even more confident writing male characters than female. I don’t know if it’s because our main female characters are too much like us and therefore we find it hard to see them as fully realized characters at first? What do you think?

NJ: Yes, exactly. Maybe as a black woman writing Ruth’s story, it hit so close to home that I was afraid to “go there.” But in revision I think I did go deep and make it as revelatory as possible. For example, Ruth clicks the automatic locks in her car in a predominantly black neighborhood and feels immensely guilty for internalizing this fear of her own community. Also, when she’s driving with this white kid in her car, she’s worried about their safety in a white area and she’s acutely aware that she could be wrongly perceived as a mammy figure in his life. Those are just a few of the complicated, real moments I want readers to experience.

In your novel, Nora is a white woman who is thrust into this explosive situation of loving a black man during the Detroit riots in the 1960s. We talked about how much you have in common with her because you were raised to mind your own business and not draw attention to yourself in big political moments. But as a woman of faith and principle, there’s this pull to act on your conscience and take a stand. That’s a perfect example of where I thought you could draw upon your own internal struggle to make Nora’s story richer.

EB: One thing I’m looking forward to as our relationship as critique partners develops is getting one another’s unique point of view on things other than issues of race or diversity in our writing. By that I mean, on the next thing you read for me, I’m not going to be looking for your opinion as a black woman, but as a woman. And I felt that much of the time I was reading your book, I wasn’t thinking of myself as a white woman. Sometimes I was reading as a pastor’s wife. Sometimes I was reading as the mother of a young boy. I imagine that it could get irritating or tiring for you to only be approached for your opinion as a black woman and not any of the other things you are.

NJ: Oh yes, you definitely get it. While I’m passionate about race and diversity, that’s not all of who I am. I was bullied as a kid, not for being black, but for being smart and tall with an Afro at a time when the other girls at school wore their hair braided. In addition to being a daughter and a single working woman living in Chicago, I’m also a cancer survivor. I spent many years as a journalist covering everything from the Bush v. Gore presidential recount in 2000 to the Spice Girls concerts. So, like you, I bring a lot of life experience to the page as both a writer and critique partner. As I wrap up revisions on my own book, I’m anxious to dig in to your new novel!

Tell us about your critique partners. How have their perspectives helped you see around corners and improve your books?

What unique backgrounds and experiences do you and your critique partners bring to the relationship?

I love the comment from Erin about how getting feedback can be like someone telling you your fly is down. You may be embarrassed, but you’re really glad someone has pointed that out!

Ha! Yes, I laughed out loud when Erin said that! It’s so true though. We don’t know what we don’t know until someone tells us. It takes equal courage to give and receive that kind of feedback. Thanks, Densie.

“We don’t know what we don’t know until someone tells us. It takes equal courage to give and receive that kind of feedback.”

YES.

Both the giving and receiving is uncomfortable, but I think that not only the writing comes out stronger in the end–the relationship between giver and recipient can come out stronger as well. How many relationships do we really have where we feel we can be 100% honest with each other and still maintain love and respect on both sides? Far too few, I’m afraid.

I was thinking the same thing! It’s so true. It’s always better knowing and having it come from someone who cares about you vs a stranger leaving a snarky review!

Interesting discussion, Erin and Nancy. I’m particularly provoked by the fact that, as Erin put it, you both “feel more comfortable and perhaps even more confident writing” characters of the opposite sex. I’ve long been tagged with having my female protagonists being more relatable and easier to connect with than the male ones, and I’ve struggled to figure it out.

Though I feel I’ve taken steps to rectify the issue during the revision stages, I fear my efforts feel like just that: rectification. And though I’m confident in my storytelling, and I’m certain I’ve strengthened my males during revision, I sometimes worry that, without providing that sort of connectivity for my male protagonists during the creation and initial drafting, I’ve yet to deliver the genuineness for one half of my male/female protagonist combos that is fundamental to taking my work to another (perhaps breakout?) level.

Do either of you identify with that fear (about not being able to “go there” during conception and drafting – in regard to gender or race, or both)? Or do you feel everything can be overcome during revision?

Thanks for a frank and illuminating discussion. Looking forward to reading you both!

Oh how fascinating that we are not alone in our little conundrum writing about men/women. My first thought is that perhaps we feel an innate need to more thoroughly explain or draw out the characterization and motivations behind characters of the opposite sex because we’ve thought more about how they work and function in the world than those of our own sex, which we may take for granted. But maybe it’s more than just that.

When I revise, I have to work much harder on making the women and their actions understandable than I do the men. I don’t know if it’s exactly being afraid to “go there” or not, or if it’s kind of like Nancy being able to write white characters well because she has functioned in white spaces her whole life, whereas I have to work harder to write black characters because I grew up in a town that was 99% white. So when it comes to men and women, if you’ve functioned in a so-called man’s world maybe you have observed it more closely than the world of women. Or vice versa. I do tend to prefer hanging out with men to hanging out with women. I’m never the one in the kitchen doing dishes after a meal talking about raising children; I’m sitting with the guys smoking a cigar and talking politics, theology, books, and movies.

And on the subject of critiquing, I always get at least one early male reader to go through a manuscript and let me know if he thinks “this guy would never say that” because I get SO irritated when men write women who feel like they are just there to further the male character’s agenda or make him look clever. But I definitely hear from early readers more questions of “Why would she do this?” than “Why would he do this?”

Thinking of your writing, I wonder if maybe you’ve often been the only man in a room full of women as I’ve been the only woman in a room full of men. That fly-on-the-wall position is a good one to be in for a writer!

Yup – Raised by a very strong mom, with a fairly soft-spoken dad who always welcomed that strength. I also had two sisters, and the job that took me through college was being the maintenance man at a women’s fashion store (Gantos at Meridian Mall, as my fellow Michigander may recall it), where I was the only male. It was fascinating being in that dynamic, as the lowest on the employee totem pole, with all female management and coworkers (it’s where I met my wife).

I’ve always loved hanging out with my wife’s friends, as well. When they’ve planned all-girl outings and get-togethers, they often joke that, of course I can be included (the joke being that none of them would presume to include their male partners).

I’ve pondered “not wanting to go there, because males represent me.” It’s an interesting notion that I might be taking masculinity for granted. That’s worth consideration, as it still seems like I’m not fully understanding my own lacking. And I still worry about my revision efforts to heal it. Thanks for the insight, Erin.

Thanks, Vaughn, for the question and discussion. I think of masculinity and whiteness as the default in our culture. There’s also enough distance from my own experience that I find it a fun challenge to inhabit “the other.”

When I’m writing a female character, I’m always writing some part of me. That’s scary. There’s a fear of being vulnerable on the page. As I review my revised manuscript, I often wonder “will they think this is about me or think that I feel this way?” I guess it’s a baring of the soul and I tend to sanitize a bit in revision, which probably isn’t the best way to do an honest reckoning in one’s work. Thanks for helping me figure that out. :)

Nancy, I felt that fear every time I had to let a character be racist in their particular way! “Will they think this is what I think?” Yikes.

I have that same fear, Erin. My stories are inhabited by fictionalized characters based on people I have known. In my current WIP, I have to write about both racist whites and black people in the Civil Rights Era South. Very tricky! I need a beta reader who can give me insight but alas I lack anyone at this point.

From the title to the photo to the forthright content of the interview, this was just wonderful, Nancy and Erin. Congratulations for tackling the challenges of writing diverse major characters with such sensitivity. Sounds like you are lucky to have each other!

I have two full manuscript readers that I use on a regular basis. The more commercial writer for teens calls me out on things like show-don’t-tell and what dialogue seems believable. She tends to want to clean up my intentional sentence fragments. But she also goads me into “going there,” as you say. Not unlike her to say, “This is the moment we’ve been waiting for—why did you gloss over it?”

The more literary writer gives me a lot more leeway as concerns style—if I make a case for it, she buys it—which reveals her interest in the psychological through-line. That’s where she calls me out. Not unlike her to say, “Why on earth would she say something like this?”

Together, keeping their individual points of view in mind, they are quite valuable to me!

Great point about having multiple readers for their multiple strengths and perspectives! That also guards against our writing being too influenced by one outside voice.

I’ve worked with several writers as an editor and asked them why they did certain things in the story, to which the answer is, “My crit partner told me to do that.” Many times in the discussion about it they admit that they didn’t feel it was the right thing to do, but they followed the advice anyway, and now after doing that on a number of things, they feel like the story isn’t there’s anymore. That’s always something we have to guard against.

*theirs

Exactly, Kathryn. I have several readers, too, and they’ve all provided such unique insights. Some notice that every character exhales a held breath while others point out inconsistencies in the timeline. Still others can tell me where the story’s momentum flags and the parts where their expectations weren’t met. All of it is a gift as I revise.

After my week-long workshop at Tin House, I was confused and overwhelmed by all the critique. I asked the author Benjamin Percy for advice and he said, “Go where the electricity is.” It’s always about what feels right for me as the writer. Thanks, Kathryn!

Wow! I absolutely love the honesty of this post and the levels you each were willing to reveal and accept as part of your relationship as critique partners. I definitely can appreciate your perspective, Nancy on writing black female characters and sometimes having a better go with writing male characters. And Erin, I remember you talking about this book nearly two years ago when I met you at the WFWA Retreat. I am thrilled about your starred review and am looking forward to reading this story–and I must say, reading this post has piqued my interest in doing just that. Knowing how hard you worked to ‘get it right’ is very important. Excellent post, candid sharing. Well done!

Thanks, Denny! There will still be things I’ve gotten wrong, but it won’t be for lack of trying! :)

Hi, Denny! Yes, I know you can relate on many levels. As a black writer, I’m always thinking about responsibility not only to the story I’m telling, but also to the black community and to my desire to build empathy across racial lines. That’s a lot for any writer to shoulder.

I like what you said about honesty in the critique partner relationship. It will hopefully serve Erin and me well going forward as we have more difficult conversations on other topics in our writing. And yes, Erin’s book is fabulous. I know! :) Thanks for commenting, Denny!

I love this!! Candid conversations like these are so critical. The beautiful honesty between the two of you is rooted in respect and admiration for culture, race, and person and I am grateful for this peek into your behind-the-scenes. As a white girl raised in a white culture in a predominantly white small town, it’s such a privilege to see the perspectives outside my little boxed-in and often unintentionally ignorant world and help bring understanding to a sensitive yet beautiful topic. So thank you both for this pertinent and vulnerably honest post.

Great to see you here, Jaime!

Yes, it has been a long, sometimes embarrassing, always fascinating road from my small-town upbringing to now living in a bigger and busier city that is only a little more than 60% white and filled with people from every culture and continent through domestic migration, a huge international student population, lots of refugee groups and immigrants. I wouldn’t trade having my son grow up in this environment over the monoculture I grew up in for anything. :)

Jaime, hello and thank you for your kind words! As I always say, we don’t know what we don’t know. I appreciate your honesty, too. It is up to us though to broaden our experience and get to know people from other backgrounds. It’s a risk for all of us when we do it, but definitely worth it. It makes our writing and our lives richer. Thanks again!

Thanks for writing so candidly. Frank and open discussion by critique partners is the hallmark of a good critiquing session. It needs to be said factually and the listener/writer needs to understand it is to be helpful. Putting one’s ego aside and investment in our writing can be hard, but always makes for a better end product: a great book. You two are lucky to have each other and I hope for the same for the other readers of this blog.

Thanks, LaDonna! The ego, yes! So hard to control.

Well-said, LaDonna! We’re so emotionally tied to our writing that it can be hard to put aside ego. I know it’s tough for me to do. The nice thing about having a critique partner you trust is knowing all feedback is in service of the story. And it’s all love. :)

I really enjoyed this post. So glad that honesty won out over any potential embarrassment. Good critique partners are gold. I have a couple of trusted partners and they always help me to see my story more objectively. They ask just the right questions.

Thank you, Vijaya! Objectivity is the name of the game, isn’t it? We can never see our own shortcomings as clearly as others can.

Yes, Vijaya! I try to go into every story with questions. This time it was about race and motherhood. Erin did a nice job asking questions that forced me to dig for deeper meaning. I appreciate that push to explore in new ways I hadn’t considered. Thanks!

I loved everything about this post—thank you both for giving us a look behind the curtain at what a great critique partnership looks like.

Two favorite parts were the ‘fly down’ analogy and about looking at work as being so much more than a ‘black woman’ or a ‘white woman.’ We are so many things and bring all of our perspectives with us when we sit down to read a story.

Thank you again for sharing!

Thanks, Alison! For this book I asked a rather large number of people to read it, almost all for specific reasons. Beyond black readers, I asked a historian, a sociology professor, former residents of Detroit, and others to read with an eye toward their own special skill set or background. Even with all of those perspectives, I’m sure I missed something!

Hi, Alison! I must say that you, too, were a most exceptional reader of my manuscript. I can’t even describe how helpful it is to have that outside perspective.

It’s funny that you and Erin asked in the margins what sidity/saditty means. I hadn’t realized until then that it was African-American Vernacular English. It’s a term used to describe someone uppity or superior-acting.

Thanks for commenting!

This is so perfect! I had an elderly black man in my second book, along with a younger female character who was Mulatto (she’s in both books.) I’d thought I did a good job on both characters, especially the elderly man since I based him on a sweet black man I’d befriended years ago.

I was wrong!!!! At one point I had the female’s teen daughter say “Mom’s such a slave driver,” never thinking about it at all. After the book came out, someone mentioned they probably wouldn’t say that and she was right. Also, the wife of the elderly man I’d befriended (who passed away a few years ago) told me no black man of his era would have touched the arm of a young white lady he barely knew (which I had my character do.)

There are so many behavior characteristics that we don’t think about for someone whose skin color is different than ours. I’m glad you two were honest with each other. Your stories will ring true that way!

Hi Jill! Great examples. Sometimes we can miss the boat big time, but in many instances it is the accumulation of tiny details we just wouldn’t see from our own lens without having someone else look at things from another angle.

For me, one of the people who helped me with those little details when it came to life in Detroit in the 1960s was my father. He could say, no, if that guy worked for GM he wouldn’t live in Dearborn, he’d live in Bloomfield Hills. Or while a white man with a white collar job may drive an Impala, the black character who has a blue collar job might drive a Biscayne (which was the exact same body as an Impala, but with far fewer high-end details). He even remembered the names of the drive-in theaters he would go to versus where black kids his age would go. Those little details are important, especially since so many potential readers in the Baby Boomer age bracket used to live in Detroit (it’s been losing population since the 1950s, but all those people are somewhere out there if they’re still alive).

Thanks for those examples, Jill! There are plenty of words and phrases like “slave driver” that people use casually in conversation without thinking about the historical implications. That’s why it is helpful to have others point out our blind spots.

Not to complicate things, but it’s important that we don’t make assumptions though based upon stereotype. You don’t want to put a race of people in a box, limited by your own experience. What I’m trying to say is there’s more than one way to be black in America. We’re not a monolith and the stories we create should reflect that.

Thanks for sharing!

Yes, Nancy! I think you did such a great job showing that in your book, and I tried to do so as well. I really didn’t want to paint all of the black characters in my book as victims, which meant letting some of them show racism or violence as well. And then as the writer I worry about critique of that choice.

Wonderful write-up! My current WIP deals with issues of race, and it’s such a challenge to get it right. Critiques of the kind you describe are definitely essential. Thanks so much for sharing this!

Rebecca, hello! We’re always trying to “get it right” when we write about race outside our own perspective. My advice is to do the research and find a diverse set of readers who can provide perspective. Then, be willing to graciously accept the criticism that WILL come. Learn from it for the next story you tell. Thanks!

Thanks, Rebecca!

Thank you for a particularly insightful post! I’m impressed with your candor and that you put into words what so many of us feel or fear. Well done, Nancy and Erin!

Hi, Michele! You and I have these candid conversations as well. The more we’re willing to talk about the hard stuff, the better our stories will be. I truly believe that. Thanks for commenting!

Thanks, Michele! I think we’re so afraid of saying the wrong thing because of how quickly people get torn limb from limb online, even for honest mistakes that aren’t driven by malice. It’s a blessing when you find people who can talk about difficult things and remain friends while doing so.

I am really late writing to you both today, but admire all that you have done in creating this post and the sharing and analyzing that has gone into your evaluation of each other’s work. So valuable. Erin has read an early version of my WIP. Nancy has evaluated my presentation of the black detective in my novel. Your advice on all fronts has been woven into my rewrites and underlines the value of candid analysis and the necessity for rewriting. Thanks for sharing your journey. Beth

Oh, thank you, Beth!

Beth, I appreciate that and can’t wait to see your gorgeous novel published.

Thank you for letting me “listen in”. This was a very interesting discussion on how to give and receive feedback effectively from a fellow writer.

Thanks so much, Leanne! We were happy to share and have a dialogue about it with all of you.

Thanks for reading, Leanne!

I loved this dialogue between the two of you–open and honest! Thanks for sharing it with us.

I’m glad you enjoyed our conversation, Carol! Thanks for being part of it.

Yes, thank you, Carol!

This discussion was great and made me want to read your books to see how you handled these sometimes thorny issues. I’m interested as a reader in seeing the richness of race, culture, ethnicity, etc depicted without stereotype. As a writer, I want to be able to do the former, LOL. PS I have a mixed race daughter and grandchildren who live in a predominantly white state so am personally invested in positive and truthful representation.

Liz, hello! I like what you said about “positive and truthful representation.” I believe both are important. The beauty of it is that when we create more diverse stories, there will be many rich and varied representations of what it means to be black or immigrant or woman in this world. When we have limited stories, we get limited perspectives.

I can understand why you have a personal investment in this. Thanks so much for commenting!

“Richness” yes. Both Nancy and I are trying to avoid not only poor representation of “the other” in our work, but trying to attain a rich representation. I don’t want any skim milk characters, whatever their color, if I can avoid it. Let’s go for whole, rich characters. Thanks for your comment!

Really late to the party with comments. Still no internet after the hurricane and at the mercy of @#%! cellphone. Great article, guys! Nodding head in agreement with previous comments. I, too, appreciate the candor. You showed not only how to have these conversations, but also that those same conversations can be rich in resources and new understanding. I envy-in-a-nice way your critiquing partnership. Honest, deep, caring CP relationships are priceless! Erin, I’ve preordered your novel. It sounds great! And Nancy, I can’t wait to preorder yours. :) I remember reading small excerpts in a class, and the concept was riveting.

Thanks so much, Kathy! Hang in there. Seems like half the people I know are recovering from something–another reason for us to treat each other with gentleness and understanding. :)

Hi, Kathy! Sorry you’re dealing with the frustrations of the hurricane aftermath. Ugh. Yes, it’s all about new understanding. I see the world through the lens of my lived experience. Erin has helped me broaden my view and bring more complexity to my characters.

I’m glad you enjoyed the excerpt you read from my novel-in-progress. I’m even happier that you’ve preordered Erin’s novel. You’ll love it!

Hope your internet is back up soon. :)