Shakespeare in Space – with Lasers!

By Keith Cronin | February 13, 2018 |

I recently stumbled onto an online discussion about animated films, where somebody referred to The Lion King as having been inspired by Shakespeare’s classic play Hamlet. That was news to me, and it made me think about other films that I had belatedly learned were inspired by Shakespeare plays, such as 10 Things I Hate About You (The Taming of the Shrew) or My Own Private Idaho (Henry IV and Henry V).

I recently stumbled onto an online discussion about animated films, where somebody referred to The Lion King as having been inspired by Shakespeare’s classic play Hamlet. That was news to me, and it made me think about other films that I had belatedly learned were inspired by Shakespeare plays, such as 10 Things I Hate About You (The Taming of the Shrew) or My Own Private Idaho (Henry IV and Henry V).

This in turn got me thinking about how little I actually knew about Shakespeare. True confession: until about four months ago, my Shakespearian awareness was largely limited to a 1966 episode from season 3 of Gilligan’s Island, where the castaways perform a musical adaptation of Hamlet for a famous movie producer currently stranded on their island (hey, it could happen). Behold, in all its glory:

Boning up on the Bard

While I’ll admit that episode is fondly etched into my cultural DNA (yes, I’m deep), I realized I needed something more. After all, now that I am supposed to be a Serious Writer (said with the appropriately furrowed brow, and the sincere intent to someday purchase a tweed blazer with leather elbow patches), this scarcity of SSC (Shakespearian Street Cred) seemed inexcusable. So I took advantage of some recent time off from the DDG (dreaded day gig) to remedy this gap in my cultural literacy, and went off to my local library to load up on books and DVDs. I tend to be a total-immersion kind of guy when I develop a new interest, so the next several weeks were all Shakespeare, all the time. The results were illuminating. First, there was the fundamental question:

Just how big a deal is this guy?

Pretty darn big, as I was soon to learn. As literary critic and expert on all things Shakespearian Harold Bloom observes in the forward of Susannah Carson‘s book, Living with Shakespeare: Essays by Writers, Actors, and Directors, Shakespeare is “the most widely read author in English; his Complete Works are second in popularity only to the Bible.” (Take that, James Patterson! Suck it, Clive Cussler! But I digress…)

Okay, so the guy’s a best-seller. But Shakespeare’s impact is broader and more profound than the sheer size of his readership, as Bloom elaborates:

We live in Shakespeare’s world, which is to say that we live in a literary, theatrical, cultural, and even psychological world fine-tuned for us by Shakespeare. Had he never lived, we would have bumbled along well enough, but he did live, and he did write, and those works were printed, and read, and performed, and passed on, and read some more, and performed some more, and emulated, and assimilated, and quoted, and so on. So that now, four hundred years later, we continue to read and perform and emulate his work so thoroughly and passionately that it’s difficult to conceive who we would be – as a culture, as ourselves – had Shakespeare never existed.”

Those are some powerful claims, and worthy of further examination. Let’s first consider Shakespeare’s impact on the English language itself, which is considerable. This site postulates that Shakespeare contributed over 1,700 words to the English language. How? By “changing nouns into verbs, changing verbs into adjectives, connecting words never before used together, adding prefixes and suffixes, and devising words wholly original.” Some examples include frugal, moonbeam, zany, and puking.

Take a moment to absorb that: The dude gave us puking.

I mean, he could have quit right there and still made his mark on society, but no – he still had another 1,699 words left to regurgitate!

Probably even more memorable are the phrases and figures of speech that can be traced back to Shakespeare. This article in The Independent lists 50 of them, but I’m sure there are far more. Some of his greatest hits include the following:

- Wild goose chase

- Heart of gold

- With bated breath

- Knock knock! Who’s there?

Hang on – make sure you take this in: Not only did he give us puking; the dude gave us knock-knock jokes. As Keanu Reeves would say: Whoa.

In Isaac Asimov’s excellent book on the Bard, the author observes:

Shakespeare has said so many things so supremely well that we are forever finding ourselves thinking in his terms.”

You can quote me.

If, like me, your direct exposure to Shakespeare has been limited, when you first sit down to watch or read one of his plays, you may be surprised by just how familiar you already are with his language. So pervasive are so many of his phrases that they seem like they must simply be linguistic chestnuts the Bard borrowed from somebody else.

To illustrate that point, Asimov describes a woman who reads Hamlet for the first time and then complains, “I don’t see why people admire that play so. It is nothing but a bunch of quotations strung together.” I’ll confess to having a similar reaction the first time I watched one of the many excellent film versions of Hamlet. At first I thought something was rotten in Denmark (see what I did there?); then I realized I was hearing the source from which so many of these famous quotes and figures of speech came. Whoa indeed.

Not-so-old English

The first time you read or listen to Shakespeare, some words or phrases may seem old-fashioned and not very conversational, making his work feel somewhat inaccessible. If so, give it some time. Particularly as a listener, the rhythm and the logic of his language soon start feeling more and more familiar, and in my experience you’ll soon find yourself engrossed in the story, not just the language (although the language continues to thrill and delight).

When you think how much the language has evolved just within your own lifetime (OMG, like, for realz!), you have to wonder: why does this guy’s stuff still work so well, some four hundred years later? Author Ben Crystal takes a hard look at the supposed inaccessibility of Shakespeare’s language in his book, Shakespeare on Toast: Getting a Taste for the Bard. Crystal maintains that 95% of Shakespeare’s words are perfectly understandable to a modern audience.

95% is pretty darn good, if you ask me. I mean, I’ve got an MBA, yet I’ve sat in corporate meetings where I understood FAR less than 95% of what was being said. Well done, Bardster. Well done.

Okay, so the guy had some serious game when it comes to the languagey stuff (hey, it might be a word). But let’s take a look at some of the techniques Shakespeare used as a storyteller, starting with something I’ve noticed in every Shakespeare play I’ve studied so far:

High stakes

In particular, the Shakespearian oeuvre (a word I have serious plans to learn how to pronounce correctly someday – but today is not that day) demonstrates a willingness – you could perhaps go so far as to call it a flat-out eagerness – to kill even the most major characters. Long before there was George R.R. Martin and his highly successful “Who’s Gonna Die Next?” book and TV series (also known as “Game of Thrones”), there was Billy “The Reaper” Shakespeare. Seriously, this guy will kill anybody.

I can just see the Bard pitching his latest play to investors. “It’s called Romeo and Juliet. It’s a love story for the ages. Oh, but here’s the thing. Um, they both die. But seriously, it’s a love story for the ages – trust me! Wait – I’ve got another one you’ll love – it’s called Hamlet. Um, but here’s the thing. He dies, too. Oh, and so does his mom. And – okay, also his girlfriend. Aaaaaaaannnnnd his girlfriend’s dad. And his best friend. And a couple of other friends. And his dad, but that happens before the play starts, and it gives us an awesome ghost-story angle. Oh, and his stepfather, but that guy was a major jerk – he totally had it coming. But wait – there’s also a guy talking to a skull, and this really cool sword fight…”

The body count in a Shakespeare play can get pretty high, as illustrated in this handy infographic. But I think the lesson here is not that the Bard was into making thinly disguised snuff plays, but rather that actions have consequences – sometimes life-changing (or life-ending) ones. That’s a lesson that I think we can all use to inform and enrich our work. Got a story that’s light on conflict? Take a lesson from Shakespeare, and kill somebody.

A mixture of tragic and comic

Shakespeare’s plays are often divided into three main categories: tragedies (not surprisingly, Hamlet falls here), comedies (A Midsummer Night’s Dream is an example), and histories (basically all the ones named after dead kings). Yet you will find elements of comedy in his tragedies, and vice versa. For example, there’s the wonderfully bumbling (and eminently quotable) blowhard Polonius, who brings some comedic touches to the otherwise angst-ridden bloodbath that is Hamlet.

The light-hearted Much Ado About Nothing features a mean and manipulative twist when an act of infidelity is faked in order to sour the groom on his bride-to-be, who reacts to this humiliation by faking her own death, thus putting a bit of a damper on the planned wedding festivities. Bottom line: a Shakespeare play is going to give you some serious highs and lows. You know, kind of like real life.

The not-so-foolish fool

Many of Shakespeare’s plays feature some sort of “fool” character. In the case of the delightful As You Like It (I’m a big fan of this live version filmed in the reconstruction of the Globe Theatre where Shakespeare’s plays were originally performed), the fool is an actual professional fool – i.e., a court jester – named Touchstone.

Can’t touch this.

Although Touchstone is one of the funniest characters in the play, he’s also probably the smartest, as demonstrated by the way he casually dispenses incisive and irreverent insights and observations. A fast-thinking, nimble-tongued trickster who jokes and riffs like some 16th-century Robin Williams, this joker is clearly nobody’s fool.

It’s interesting that Shakespeare sometimes likes to give the clearest, most insightful perspectives to characters who outwardly might not elicit much respect – people who likely would be dismissed as fools. One suspects the playwright might have walked some miles in those curly-toed shoes himself, and perhaps this also helped his work resonate with the less privileged – and the less educated – among his audiences. This leads me to my next observation about El Bardo:

Shakespeare didn’t dumb things down – nor did he need to.

The second part of this statement is key: He gives the audience credit for being able to follow his plot and his language. And he shows characters of various levels of intellect, and lets the audience figure out who’s smart and who’s not – and this is often NOT related to that character’s social class or profession. Again, kinda like real life.

Caveat! (Pro tip: Try singing “caveat” to the melody of “Camelot.” Okay, now try to get that out of your head. You’re welcome.)

Okay, back to the actual caveat, which is this: Sadly, I worry that this lesson may not be as applicable to modern writers – particularly those writing for a U.S. audience. I know I’m not alone in noticing a growing trend of anti-intellectualism here in ‘Murica, and there’s a sizable segment of the U.S. population that seems to be alienated and/or turned off by overt displays of logic, wit or intellectual prowess. And when I think about the never-ending wave of dumb-and-dumber movies that keep getting made (I’m looking at you, Hot Tub Time Machine 2 and Hangover Part III), it makes me wonder whether the Bardinator could even score a development deal in Tinseltown these days.

Truly timeless stories

With all the books, plays and movies that have been inspired by the works of Shakespeare, four centuries later it’s safe to say his work has stood the test of time, with stories that are equally at home in the 16th or 21st centuries – or beyond. That’s why many of his plays have successfully been adapted nearly verbatim to a wide range of times and settings. For example, I’ve watched versions of Hamlet set in its original time, in war-torn Denmark during World War II, and in present-day Manhattan. Each time, it has definitely worked – sometimes surprisingly effectively.

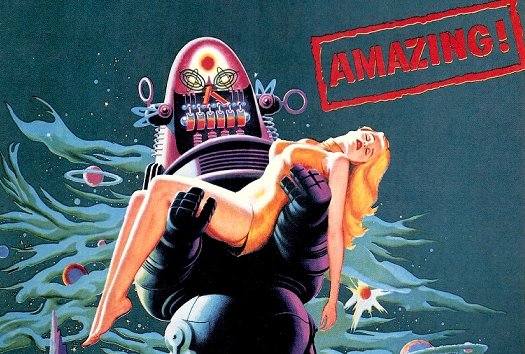

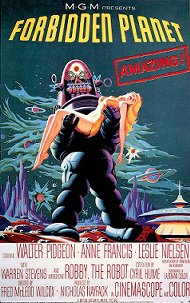

And when you get into the “inspired by” stories that do not adhere to the original text of Shakespeare’s plays, the opportunities can take you as far as outer space (with killer robots and lasers!), as with the classic 1956 film Forbidden Planet, a story based on The Tempest, which features what is possibly the Best. Movie. Poster. Ever.

And when you get into the “inspired by” stories that do not adhere to the original text of Shakespeare’s plays, the opportunities can take you as far as outer space (with killer robots and lasers!), as with the classic 1956 film Forbidden Planet, a story based on The Tempest, which features what is possibly the Best. Movie. Poster. Ever.

With or without killer robots, for me the biggest takeaway from my study of Shakespeare is this: he truly was a universal storyteller. And that’s something I think we all can learn from.

How about you?

Are you a fan of the Bard? Or does Shakespeare intimidate you (or simply leave you cold)? What lessons have you taken away from his work? How do you think his stories have stood up – or not – to the test of time? Please chime in, and as always, thanks for reading!

Forbidden Planet posters available here.

[coffee]

Nice column, one of the things I have enjoyed recently is a series of books that takes the Star Wars movies and recasts them as Shakespearean plays, complete with asides and soliloquies and the whole bit. They are quite entertaining.

Thanks, David.

Whoa – Shakespeare and Star Wars together? Talk about geek heaven! I gotta check that out.

Is this what you’re referring to?

https://www.amazon.com/dp/B00BE24WT8/

It’s brilliant, and all in iambic pentameter!

Ooh, my local library carries these!

Verily, I must hasten there!

One of my peak experiences in college (a state agricultural college, yet–also known as a cow college) was an intensive study of King Lear, in which, after we had become familiar with the play, the professor had us do two written exercises: go through the play to summarize each scene, and go through it again to trace the changes in Lear’s sanity. (I produced both of these multi-page documents on my portable typewriter, erasing and whiting out as I went along.) The lessons in structure and character development have stayed with me after all these years (ahem, decades), along with a sturdy appreciation of the Bard’s language.

Thanks for chiming in, Anna. You bring up a GREAT point, which I should have included among my lessons from the Bard:

The guy DEFINITELY knows how to capture a character who is insane – or who is losing his or her sanity.

Ophelia is a great example in Hamlet (one could argue that so is Hamlet himself), but there are many more examples throughout his oeuvre (however the hell you pronounce that word).

This was brilliant, Keith. I have a falling-apart copy of “Shakespeare’s Complete Works,” dated 1925. It belonged to my grandfather and it’s has embossed gold lettering on the leather cover. I have yet to read it all. You make a convincing argument that I should! Well done, my man.

Thanks, Densie!

I’ve got a massive collection of his works, too – I think it was on sale at Costco – but the darn thing is physically so big that reading it qualifies as a CrossFit activity.

“Danish pastry for two,

For me, for you!”

Gilligan as Hamlet. Brilliant! How did I miss that episode? Or maybe I did see it as a kid and failed to appreciate the humor? Of course I didn’t. I didn’t yet know Shakespeare. Parody depends on the audience’s familiarity with the subject.

(Have you ever seen the Reduced Shakespeare Company’s summary takes on Shakespeare plays? Their compression of the histories into one football game, with commentary, is a model of economy. Their one-minute “Hamlet” is hilarious.)

There are too many story craft lessons in Shakespeare, and in your post, to hit them all, so to your excellent observations I’ll add only this:

Shakespeare used soliloquies, passages of self-reflection in which characters take the measure of themselves, others, their situations, history, existence or even time itself. (“Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow…”)

Soliloquies do not advance the plot, but they do open up characters–even that tedious over-thinker Hamlet–in ways that allow the audience to connect to them. We connect because Shakespeare’s characters think, feel, angst and wonder as we do…or would, if we valued ourselves as much as they value themselves.

For fiction writers, what this means is that the interior life of characters is as important, even necessary, as what is happening to them. Handled as questions or declarations of the highest insights humans can have, exposition can have greater power than action.

And now to the big question: How did the shipwrecked tourists on Gilligan’s Island obtain cheesy costume crowns and gowns? But I doth protest too much, methinks. Great post, Keith. Your Hollywood pitch for “Hamlet” had me laughing out loud.

Thanks, Donald.

I’ve learned there are many questions regarding Gilligan’s Island that are best not to think too much about. :)

I haven’t seen the Reduced Shakespeare Company’s productions (although I’ll be watching your link shortly) but one of the books I found very helpful in my studies was authored by its founders:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/1401302203/

Great point about self-reflection (and it sounds like I’m not the only one who found the character of Hamlet to be a bit of a brooding drama queen). Shakespeare really takes you INSIDE his characters’ minds, in a way few authors do as vividly. Good stuff!

Ah, the Bard! In a former life I was a high school English teacher, so I can quote story-and-verse about Romeo and Juliet, Julius Caesar, and my favorite, MacBeth.

Right now, the Yale annotated copy of the Complete Works serves as a base under my laptop.

I figure it can’t hurt…

Lakota, that massive tome has got to elevate your laptop by at least 4-5 inches, right? :)

Here it is: the one-minute Hamlet…

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H2Jzkop04P4

…and backwards too!

LOL – backwards for the win!!!

Thanks for this interesting post Keith! My first traditionally published novel, The Medievalist, is about Richard III, whom I am convinced would be an obscure monarch (he reigned less than two years) if Shakespeare hadn’t made him into the consummate villain. Then I’d have had to find someone else to write about…

Anne-Marie, I’m glad the Bard’s interest in writing about history helped support your own interest in writing about history!

Keith, I really enjoyed your piece today. I was terribly intimidated by Shakespeare until my kids were in middle school. One of the highlights was the kids making up their own modern play based upon what they had read in class. Great fun. I realized then how timeless his stories were and like you began to read his plays. What helped was to read Charles and Mary Lambs first. Over the years, I’ve discovered Shakespeare insults which have made their way into my stories. I am thankful that the principal of that middle school was a “failed actress.” We are that much richer.

Thanks for commenting, Vijaya. And I’m glad you – and your family – have found the fun in Shakespeare!

Great article. I have found pleasure in Shakespeare later in my life. Maybe when his wisdom could be fully appreciated. I had not realized so much about him, so thank you for the background and knowledge. Now you have wet my appetite and I want to learn more.

Thanks, Elizabeth – I’m glad to see I’m not the only “late bloomer” when it comes to appreciating Shakespeare!

OMG! Gag me with a spoon! A post about Shakespeare. This is so cool. And… that Gilligan’s Island episode rocked, I know, because my siblings and I reenacted it at home in the backyard.

I was exposed to Shakespeare at an early age. My eccentric English mother made us read classics ’round the breakfast table (yeah, a breakfast table complete with a silver teapot, and eggs in eggcups–try living that down with your Wheaties eating friends) and my mother would do (I now realize not half bad) impersonations of Laurence Olivier in Shakespeare and the Greek classics from stage plays she’d seen in her mysterious-stone-age-life-before-kids-in-London. Thanks for the memories, I miss my mom everyday. And, I think I’m going to take a leaf out of your book and have a Shakespeare immersion. It’s time. Again.

Great post, Keith! In a world where top agents are advising writers that you can’t claim to be inspired by any book older than five years, it’s good to think about this guy that’s work has lasted over four-hundred.

Enjoy your immersion, Bernadette – I certainly enjoyed mine!

“In a world where top agents are advising writers that you can’t claim to be inspired by any book older than five years, it’s good to think about this guy that’s work has lasted over four-hundred.”

Amen to the above!

Thank you, Keith. I loved this post. If I were still teaching high school English, I might use it as a handout to introduce the kids to the joys of reading Shakespeare (and why we do it).

You said: “I know I’m not alone in noticing a growing trend of anti-intellectualism here in ‘Murica, and there’s a sizable segment of the U.S. population that seems to be alienated and/or turned off by overt displays of logic, wit or intellectual prowess.” Yes! I think that’s why we need Shakespeare and the study of the humanities more than ever these days. It’s hard to fathom why anyone would disdain the incredible gift of human language in all its complexity, nuance, and richness, considering what language has done for the species.

I’m glad you enjoyed my post, S.K. And that you share my love for how language can enrich our lives, particularly in the hands of a master like that Shakespeare guy.

Keith, I’m with Don in bafflement about not remembering the Gilligan Hamlet work, since I pored over the island doings with deep attention. I love that Willie the Shake guy: I got to play Cassius (an honorable man) in a 7th-grade Julius Caesar, and I put a lot of pork in the production.

I had a marvelous Shakespeare instructor in college, who was Indian, and his accent when he would read the lines was the mellowest of fine tobaccos. Here in Santa Cruz, CA, we’ve had a fine Shakespeare troupe for years; King Lear always kills me: “Blow, winds, and crack your cheeks!” Lear’s fool is an astute figure as well.

You probably already know this, but it wasn’t Francis Bacon who turned out to be the mystery writer of some of Shakespeare’s plays, it was Kevin Bacon. Who knew?

Tom, I’m pretty sure Kevin Bacon invented bacon, too. Which makes you wonder why he hasn’t been sainted yet.

Or if someone insists on a short version of how much Shakespeare gave us, imagine:

1) William Goldman writing another hundred *Princess Bride*s.

2) His fans running the world for a few centuries.

3) Now, imagine the stories were even better–

Wait, don’t have to imagine the last part.

Then there’s the Hamlet song, here performed by John Roberts. My son sang it before a college production of Rosecrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead to remind the audience of the events in the previous year’s production of Hamlet.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WCVikUK8XYA

Great post, Keith!

Thanks, Barbara – and that song is brilliant!

Hi Keith,

Sorry to come so late to the party, especially because I’ve loved Shakespeare since I read the Charles and Mary Lamb truncated version in school.

My first deeply emotional experience of Shakespeare was the Franco Zeffirelli ROMEO & JULIET in 1968. I was in 7th grade, made two of my friends memorize parts of it with me so we could do lines on the playground, and listened to the complete soundtrack (the whole movie on albums!) so much my mother probably had it memorized. To this day, I can’t watch it without tears. Even the small parts were brilliantly cast – Robert Stephens as the Prince, John McEnery as Mercutio, Milo O’Shea as Friar Laurence – oh, I could go on and on.

HAMLET for me will always be Richard Burton. I listened to it in high school, and then found it on DVD at a library. Did you know William Gibson (MIRACLE WORKER) wrote a book called SHAKESPEARE’S GAME in which he claims HAMLET was published as copied down by someone sitting in the theatre, and in the wrong order! So according to him, if you move some of the scenes around it becomes a tight, taut storyline and Hamlet a much more understandable and credible character. I actually cut a script apart and repasted it together to see if I agreed, though that was many years ago. His arguments made sense, but I’d like to take a look at it again.

My work-in-progress has its title taken from TWELFTH NIGHT, which is my favorite Shakespeare play, and the play is rehearsed and performed as part of the novel (it’s set in a classical repertory theatre). It’s one of the plays I’ve seen the most – one wonderful year I saw five different productions: one in Canada (Stratford Festival), one in England (Royal Shakespeare Company), one on television, and two on stage in Pittsburgh. My favorite version is the Trevor Nunn film (1996) with Imogen Stubbs, Helena Bonham Carter, and Ben Kingsley. It’s the only version I’ve ever seen that gives a real feel for the love between the twins, so that the ending becomes quite moving.

I was tremendously lucky to spend many weekends and weeks at the Stratford Festival in Canada, beginning when Robin Phillips was artistic director and bringing in Maggie Smith, Brian Bedford, Peter Ustinov, Jessica Tandy, and Hume Cronyn. Incredible work – I’ll never forget Maggie Smith as Beatrice and as Rosalind.

The unexpected result of a week of Shakespeare performances daily, sometimes twice in a day, was that I found myself thinking in Shakespearean language. It didn’t last, of course.

Good luck to you in your explorations, Keith! I hope you enjoy it as much as I have. If you ever get the chance to go to Stratford and see it on stage, you might enjoy it. There’s nothing quite like seeing it in person…