The Gang’s All Here

By Guest | September 11, 2017 |

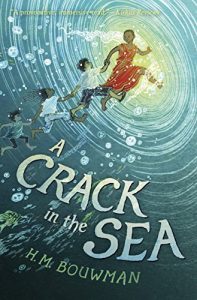

Please welcome back H.M. Bouwman H.M. (Heather) Bouwman as our guest today. Heather is the author of two middle grade children’s fantasy novels—most recently, A Crack in the Sea (Putnam/PRH, 2017). She lives in St. Paul, Minnesota, with her two kids, and she teaches early American literature and creative writing at the University of St. Thomas.

Please welcome back H.M. Bouwman H.M. (Heather) Bouwman as our guest today. Heather is the author of two middle grade children’s fantasy novels—most recently, A Crack in the Sea (Putnam/PRH, 2017). She lives in St. Paul, Minnesota, with her two kids, and she teaches early American literature and creative writing at the University of St. Thomas.

Connect with Heather on Facebook and on Twitter.

The Gang’s All Here

When I wrote and revised my recent middle-grade novel, A Crack in the Sea, I spent a lot of time thinking about ensemble casts and how they work. Crack (as my editor and agent often called it; I always worried that somehow our emails were going to get tagged for illegal activity) was a multiplotted novel in which several of the plots—and their respective protagonists—eventually came together; and there wasn’t a clear “winner” in the protagonist category. They were all important to me and, I hoped, to the reader. But how does an ensemble cast work in a novel, and how can authors keep readers engaged when there isn’t one main character for them to bond with?

The Ensemble Novel: Defined

There are several kinds of novels that we generally think of as having ensemble casts. There’s an almost-ensemble cast, in which many characters are working together on a particular project, and the reader often moves from a focus on one character to another as the project progresses. Heist books (and movies) often fit in this category, and in children’s novels, Varian Johnson’s excellent Great Greene Heist and its sequel come to mind. Often in these books, however, there are one or two characters who emerge as the key players (which is why I would call them almost ensemble casts); in Johnson’s book it’s the Jackson Greene of the title. All the other characters agree that this person is their leader, and although the action of the book might be equally shared, the thematic interest and character development is more focused on the lead character.

In children’s literature we can also find an ensemble type known as the family story, an old-fashioned novel that focuses equally on all the siblings in a family. (Think of books by classic storytellers like E. Nesbit, Edward Eager, Sydney Taylor and Elizabeth Enright.) There aren’t many of these kinds of novels today—maybe in part because families are often smaller?—but Jeanne Birdsall’s The Penderwicks series is a good example. Various chapters will focus on different siblings as they each get their own adventures; plots are generally episodic; all characters have some moments of growth and change. An adult analogy might be a friends’ reunion story, like the movie The Big Chill.

Something (Or Somethings) Shared: The Anchor

But the type of ensemble story that interests me the most contains a varied group cast—pulled together for reasons they may not even know about or understand—and multiple story lines, and often contains multiples of other things, too: settings, time periods. But somehow it all pulls together. (Think of Jennifer Egan’s A Visit from the Goon Squad, for example.) Without a single protagonist, single plot, sometimes without even a single setting or time period, we might ask how the book manages to hold together at all?

The answer is fairly simple, really: there needs to be something (or somethings) that is shared, and you as the author need to know what that is and focus on it. In Goon Squad the connecting threads are the exploring of various aspects of the music industry; the periodic musings on the passing of time; the reader’s own interest in how characters’ lives briefly intersect; and the many characters’ inexorable movement toward a unifying event at the end of the novel—a shared concert. Kekla Magoon’s How It Went Down opens with a shooting; the rest of the book, though it moves among seventeen or so (I lost count…!) viewpoint characters and follows their stories, keeps returning to the question of what happened at that shooting—and how the community is affected by it. That’s not only a plot moment but an important thematic consideration, and it makes for a gripping read. Goon Squad moves toward a key scene; How it Went Down moves away from its instigating scene. But in both cases there is a moment where the ensemble characters thematically come together (though in neither book are they all actually present together—there’s no group hug moment).

The answer is fairly simple, really: there needs to be something (or somethings) that is shared, and you as the author need to know what that is and focus on it. In Goon Squad the connecting threads are the exploring of various aspects of the music industry; the periodic musings on the passing of time; the reader’s own interest in how characters’ lives briefly intersect; and the many characters’ inexorable movement toward a unifying event at the end of the novel—a shared concert. Kekla Magoon’s How It Went Down opens with a shooting; the rest of the book, though it moves among seventeen or so (I lost count…!) viewpoint characters and follows their stories, keeps returning to the question of what happened at that shooting—and how the community is affected by it. That’s not only a plot moment but an important thematic consideration, and it makes for a gripping read. Goon Squad moves toward a key scene; How it Went Down moves away from its instigating scene. But in both cases there is a moment where the ensemble characters thematically come together (though in neither book are they all actually present together—there’s no group hug moment).

It seems to me that a key scene probably isn’t necessary in an ensemble novel, but it sure helps. Without that key moment, the author needs to draw stronger thematic connections. In my own novel, the thematic connections have to do with setting: the characters are all forced immigrants, and they are all as a result looking for a new home. Setting, therefore, becomes key in this book, and I spent more time developing the ocean setting of the second world than I might otherwise have done.

At the same time, I worried that my readers might be looking for a protagonist; but it was important to me that that wish didn’t get filled. It’s important to the story that there are many immigrants and refugees (and some kids who are neither), and they are all important. Several key characters come together in the final quarter or so of the novel—the storylines merge—but I didn’t want one character to rise from that pile as the hero. When many of the characters were working together at the end of the book, I moved point of view with each chapter as a way of keeping the protagonist position in flux; and with the one plot that couldn’t merge with the others (it was in a different time period), I tried to show the causal connection between it and the other story, and I ended with that protagonist so that she wouldn’t feel like simply “background” to the rest of the book.

Juggling an ensemble cast is tricky. My big piece of advice, after trying it myself, is to think of the ensemble cast as something that needs an anchor: a shared activity that drives the plot, a strong thematic through-line, a particular moment in time or a particular group dynamic that the book is exploring. And you may find that you need to write this “anchor” more fully—you might need to underscore those connecting lines with a thicker Sharpie—than you would in a novel with a single protagonist.

I’ve talked mostly about ensemble casts in novels for young people. What are some great ensemble cast novels written for adults? And are there other craft considerations you’d want to add to the discussion as you think about these adult books?

I just finished Tigana by Guy Gavriel Kay and it had a ensemble cast. All of the protags were united in the same cause, freeing their homeland from a tyrant. Most of the ensembles I have seen/read/played have this common cause that binds them.

David, I LOVE Tigana! I can’t believe I didn’t think of Kay when I was writing this post. Yes, uniting the characters around a cause is what pulls this book together. Thanks for bringing up such an excellent book.

A timely post. My WIP falls into your ‘almost ensemble’ category with story lines for the protagonist, the antagonist, and a third major character. I’ve checked the boxes for an anchor, nodes of contact between the story lines, and merging paths for the plots.

I know to stay in one point of view for each scene, but in some of my workshops, some readers still have trouble with the multiples, especially in the early chapters. Any thoughts?

Fredric, My readers also tend to get confused when I switch POV characters a lot–which often happens in ensemble cast novels. Maybe it’s a matter of being more explicit when you switch POV characters? I try to only switch between chapters, and then to clearly start the new chapter with a reference to the POV in the opening sentence (something like, “When Bob put the book down, he thought…”–which moves us really clearly into Bob’s head). I also put headings on chapters: the POV character’s name and the date/place if that has also switched. I’m writing for kids, so it’s even easier to lose my readers with a complicated story line, but I’ve seen headings in adult novels too. Maybe something to try?

What works for me as a reader is if there are going to be POV switches, is to set up each point of view with a long section focused devoted to it. Then as you get established then you can be more frequent with your changes in POV. Also Ensemble novels tend to be longer because you need the extra room. I read a book where the author tried to do the whole epic, multi-POV thing in a 300-page trade paperback siized book. I got about 50 pages in before putting the book down because she kept jumping around to characters I didn’t have time to care about.

Thanks for the post Heather, it’s something I hadn’t considered.

The Expanse series by the writing duo known as James S.A. Corey comes to mind. The anchor in that series affects different groups for different reasons, but everyone is changed by it.

Thanks, James. I’ll have to check this series out! Is the anchor in this book an event of some kind?

It’s Sci-Fi, and the anchor is a seemingly alien contagion coming to humanity as they are spreading into the solar system. It’s also a SyFy TV series.

Example of ensemble cast: my nomination goes to Little Women.

My WIP-in-waiting has four live characters and one dead one, each with his/her own desire, obstacle, narrative arc, and moment of truth. All have equal weight in my mind. So much for the notion that a piece of fiction may have only one protagonist. I am not willing to sacrifice any of my characters to this dictum. For now I am getting around this problem by making the POV clear in each scene. Not sure how long I can keep this herd of cats organized, but it’s fascinating to try. I do have one character whose moment of truth induces him to take the decisive action, but he’s not the protagonist–if indeed this story has one. I don’t think I’m hopelessly confused, however.

Anna, I love the image of the ensemble cast as a herd of cats! It certainly feels like that sometimes while you’re writing.

I think of LW as an almost-ensemble book, because even though each girl has her own story line and her own chapters devoted to her, Jo is still (I would argue) the acknowledged center of the story. Does that make sense?

I love how you work through the ensemble model here, Heather…it really makes sense. I can see I have a few new books to check out, as well, based on the comments. :-) And I enjoyed how the characters and storylines came together in CRACK–one of my favorite parts of the book!

As for ensemble examples, I’ll nominate Virginia Woolf’s THE WAVES. There are six POV characters, and they get differently weighted as one reads, but no one is really the protagonist. (Some may argue for Bernard, but I think he’s just inclined to philosophize the most. His role isn’t bigger.) One central element that holds them together is a seventh character, Percival, who never speaks directly–he’s more notable by his absence. In fact, I think the structure is a more complex version of what Woolf does in JACOB’S ROOM, where the central/missing element is Jacob himself.

I also found myself thinking of Dickens, as I read your essay–particularly something like A TALE OF TWO CITIES or BLEAK HOUSE.

I managed to get through grad school without reading THE WAVES, Alicia, but I can see it needs to go on my list. :) (Also, hi, friend!)

Alisha–JUST REALIZED I SPELLED YOUR NAME WRONG. So sorry!

Steven Erikson’s “Malazan Book of the Fallen” series deals with ensemble casts. I’m reading the fifth book in the series now, and I’ve noticed a few things about the structure he uses.

The characters in one book aren’t necessarily the same characters in the later books. A couple of characters might reappear, but readers have to be willing to learn a whole new group of people, places, and events. These are not books for readers who dislike challenging reading material. He makes me work for the payoff.

While some kind of “anchor scene” might be present, the characters often are in opposition to one another in that scene. For example, it might be a big battle scene near the end of the novel, and the bulk of the book follows several people from the opposing armies as they move toward that conflict. By using that technique, Erikson makes it harder for the reader to root for one group over the other. We’ve come to know many of them as individuals, and our understanding of their motivations makes choosing sides a lot harder. He deals a lot with shades of gray rather than good vs. evil.

The chapters are really long and feature a lot of POV shifts throughout. Again, not books for readers who don’t want to work hard. I spent the first 250 pages of the first novel wondering what was happening and who all those people were. I was confused a lot, but his abiliy to tell the story kept me reading.

I haven’t ever considered writing an ensemble cast until reading your post and Erikson’s novels. Seems like it would be quite a interesting challenge.

Ruth, I hadn’t even been thinking about how ensemble might work from book to book–you’ve given me a lot to consider here. And yes, an anchor scene could well be one of conflict–it sounds like these books contain great examples of that. Thanks!

What works for me as a reader is if there are going to be POV switches, is to set up each point of view with a long section focused devoted to it. Then as you get established then you can be more frequent with your changes in POV. Also Ensemble novels tend to be longer because you need the extra room. I read a book where the author tried to do the whole epic, multi-POV thing in a 300-page trade paperback siized book. I got about 50 pages in before putting the book down because she kept jumping around to characters I didn’t have time to care about.

David, I hadn’t given novel length explicit thought but found myself nodding as I read your comment: yes, it does seem like these types of books need to be longer. Now I’m trying to think of successful ensemble short stories–just to see what an exception to the rule might look like. :)

Just want to point out “Big Trouble” by Dave Barry and several books by his friend Carl Hiaasen. Very complicated and very funny. Elmore Leonard also gets high mileage out of ensemble casts in (what seem like) simple situations.

I’d like to try it, but I’m daunted by the Rubik’s cube aspect of those plots.

But Rubik’s cubes are fun….right? (Says someone who never figured out how to solve one.)

I’ve read Barry and Hiaasen before–but it was a long time ago, and I wasn’t thinking about ensemble casts when I read them. I need to go back and reread! and yes to Leonard–another one I can’t believe I didn’t think of earlier. Thank you!