How a Professional Editor Can Improve Your Writing

By Jim Dempsey | August 20, 2017 |

Please welcome Jim Dempsey to Writer Unboxed today! Jim is a professional member of the Society for Editors and Proofreaders and works as a book editor at a site called Novel Gazing. In his own words:

Please welcome Jim Dempsey to Writer Unboxed today! Jim is a professional member of the Society for Editors and Proofreaders and works as a book editor at a site called Novel Gazing. In his own words:

“I began my professional career as a journalist, working mostly in radio, and then, in the late 1990s, I adapted radio stories for the web. This meant editing my colleagues’ work to be read rather than heard. That took a lot of on-the-job training, courses, and a close attention to detail since radio journalists don’t need to have great grammar or spelling skills. Stories – pretty much all stories, fiction or non-fiction – have always been my passion. I studied them to get a Master’s degree in creative writing, and have always helped friends with their stories as they wrote novels. That gradually expanded to friends of friends and kept going until I was editing novels full time. I started Novel Gazing with two fellow editors in 2012, but that journalist in me still likes to get out now and then to write articles about editing, writing and, of course, stories.”

You can learn more about Jim and his services on his website, and by following him on Twitter (@jimdempsey and @novel_gazing).

How a Professional Editor Can Improve Your Writing

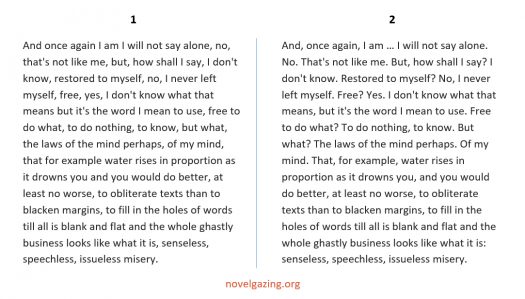

Editors do more than correct errors and rearrange sentences, they also develop a deep understanding of your book so that your readers will understand it too. Take a look at the two samples below. Which one is easier to read?

Most people would say that 2 is an easier read (note that I asked ‘easier,’ not ‘better’ – I’ll come to that in a moment).

And all it took to make the text clearer was some straightforward copy-editing. That means more than simply adding some commas and periods – the editor also has to understand what the author is trying to say.

Unfortunately, that isn’t always clear from just reading the text. Where there are doubts about the author’s intention, the editor has to ask for clarification.

This time I wasn’t able to ask the author. Samuel Beckett, most famous for writing Waiting for Godot, died in 1989.

This extract is from Molloy, and Beckett knew what he was doing when he wrote it. In the context of the novel, his style works perfectly. It emphasizes the sense of confusion. The wandering sentence is as lost as the character expressing it.

So, my revision of Molloy would be to miss the point of what Beckett was trying to say.

The understanding editor

And that’s why it’s important for an editor to understand not only what you, the author, is trying to say with each and every sentence but also understands what you want to say with your entire manuscript and how you want to say it.

To get that understanding, the editor has to read your work closely and appreciate why you have chosen those particular words and expressed them in that particular way. The editor has to know what you are trying to tell the reader.

To do that, the editor also has to see your book as the readers would see it – ideally as your target audience would see it. The editor has to spot any ambiguities, anywhere the readers could misinterpret the text or where their understanding might not match your intention.

That could mean revising something as simple as a mention of floppy disks in a YA novel set in contemporary times. Or it could be a European author writing, ‘It was 38 degrees outside,’ in a book intended for a U.S. audience – the author is imagining sunstroke conditions while the readers see the characters shivering.

Those are details, easily solved, but bigger-picture issues can be more difficult to overcome.

A clear message

This point became clear to me in a novel I edited recently (which inspired me to write this article). It was about a woman who enjoyed her life; she made the best of every day, but felt she had done everything she had ever wanted to do. She had, at 50, finished her bucket list and felt that her life was finished.

This character, to put it very simply, enjoyed the act of living but not her life.

That can be a difficult concept to grasp. In fact, it’s the kind of concept that needs a whole book to explain adequately (rather than my oversimplification above).

And, as you might imagine, there are moments in the novel when other characters don’t understand the protagonist’s point. In a way, the story is a reflection of how readers can misunderstand an author’s intention.

For that to work, the main character (and therefore also the author) has to be clear when she explains what she wants. Some characters might still misunderstand the words (as some readers will), but the author has to make sure that character expresses her intentions well.

In this case, as I read through the manuscript, I highlighted any lines that could confuse the reader, anywhere the reader could misinterpret what the character (and the author) was trying to say. I pointed out the different ways readers could interpret these lines and then suggested how the author could revise them to make the point clear.

And that’s how it works for any book, not just this one. The novel’s message doesn’t have to be precisely defined or expressed ‘out loud,’ and it might not even be immediately clear to many readers, but they at least shouldn’t be led to believe it’s something other than what the author intended.

Converging ideas

The editor acts as an intermediary between the you and your readers. The distance between your intention and the readers’ interpretation shouldn’t be too great. Where there is a gap, the editor will try to close that space by explaining to the author where any ambiguity arises and offer some revision suggestions.

A professional editor, therefore, can add the commas and periods, and even tidy Samuel Beckett’ sentences to make the text easier to read, but the real craft of an editor lies in being able to understand your novel. That’s why it’s so important to find an editor that you are personally comfortable with, someone you can be honest and open with.

But how do you find that person?

- Look in the directories of the major professional editing societies, such as the Society for Editors and Proofreaders (U.K.) or the Editorial Freelancers Association (U.S.). Editors have to achieve certain standards to become members, and the society can often provide objective mediation in any disputes you might have with the editor.

- Once you have a shortlist, have a look at the editors’ websites and their portfolios so you can see some of their previous work. Search for them on the web and social media, especially LinkedIn. Many employers make these kinds of checks these days, and you are looking to employ someone after all.

- Ask the editor to work on a sample of your work. This is the best way to see if you have that ‘click,’ if the editor understands and appreciates your work, and does a good job. And it works both ways – a sample lets the editor see if they want to work with you. Note that not all editors will provide a sample edit, and some who do may ask for payment.

The editor you eventually choose should be someone who can see your novel from both sides: yours and the readers’. That person should understand what you want to say and will work to make sure your readers understand the story in the way you want them to understand it.

Maybe you want the readers to feel certain emotions at certain times, to give them something to think about, make a moral point, put across your side of an argument. Whatever it is, a professional editor, one who understands what you want to achieve, can help you succeed.

Has a professional editor helped you to overcome issues in your manuscript? What, if anything, did the experience teach you?

Your tips for finding an editor are spot on, Jim, especially the search and asking for a little work on the editor’s end. I’ve turned away prospective clients (who I could have signed up) on the basis of the no-charge edit I did of their work because they just weren’t ready yet and it would not have been honest to take their money. I suspect searching and websites and a sample edit may give writers more to go on than a listing in an organization. I’ve been a member of two a couple of times, including the Editorial Freelancers Association, but decided I couldn’t because of the membership fees. Thanks.

Exactly, Ray.

Editing is definitely a joint process between writer and editor, and both need to know they can work together effectively. I find the free sample edit perfect for that – for both sides. Some editors complain that it’s a lot of work for no money, but, like you, it has saved me – and the writers – a lot of time and effort in the long run.

Finally! An article that speaks of editing in the way I approach editing! For once, someone is focusing on the importance of an editor viewing a novel manuscript beyond and deeper than ‘correcting’ text.

Thank you, Jim, for a wonderful, thoughtful, insightful article.

Editors are not your English teacher, grading your work. As Jim says, we are the bridge between you and your readers. Your translator, your interpreter.

Thanks for that, Maria. Interpreter is a good word for what we do. A good interpreter, or translator, has to understand the content to be able to do a good job. That describes it much better than the term I used: intermediary. I should have run this by you first.

Jim

Your post offers useful info for those in need of an editor–which (in my view) would be anyone who doesn’t have one. I especially appreciate the way you begin, by showing how an editor might actually go wrong, by not having a clear idea of what’s going on in the writer’s (Beckett’s) story.

“The real craft of an editor lies in being able to understand your novel.” Assuming the editor is smart, has read with care, and has a clear understanding of the manuscript, this makes very good sense to me. It means the editor can also reveal to the writer what’s missing, or shouldn’t be there.

But editors are like other readers, in that they have likes and dislikes. Since the editor is in business, only the most hopeless cases of manuscripts unsuited to editing are likely to be turned down. Even so, the editor won’t think about all genres or voices in the same way. Finding an editor who is truly compatible and sympathetic with one’s kind of novel–there’s the rub. The only way to gain confidence in this regard is to find an editor who has worked on books similar to yours. Unless the editor’s website identifies the books he/she has edited (yours does), I don’t really know how to go about that. Membership in professional societies won’t help there.

You’re right, Barry. It is crucial to find the right editor. I still think the sample edit is the best way to do that. If the editor is also a member of an recognized professional editing organization AND has worked on similar books before, then there’s an even better chance of getting a good job done.

Thanks for your thoughts.

Jim

I like what you said about how an editor “. . . will work to make sure your readers understand the story in the way you want them to understand it.”

I have spent almost a year trying to find an editor. The EFA is a good place to look, but going to the websites of these editors and I find discrepancies in what was posted. Most do not provide sample edits, which I can somewhat understand, but they also want a signed contract for full payment without allowing me to know their true skills.

Many writers I’ve talked to provide horror stories about editors they’ve worked with. It is a frustrating endeavor, I think almost as hard as finding an agent. Your post was certainly encouraging.

It’s those horror stories that drive me to write these kinds of articles, Stanley, to try to explain exactly what we do and what authors can – and should – expect.

There are a lot of good, professional editors out there who feel the same, and the editing associations do what they can too.

This shouldn’t be a frustrating process for writers. It should be easy and straightforward because all the good editors are in the job to help writers, to give readers great books. Writer Unboxed goes a long way to make it easier for us all too, by providing this platform for anyone interested in the craft of writing to exchange ideas and useful information to help writers avoid those horrors and frustration.

All the best,

Jim

Even though I am an editor, I do hire others for my books, and I shy away from any who ask for full payment up front and a signed contract. I will pay half up front – which is what I ask of my clients – but I have never signed a contract for editing services and I don’t ask clients to sign one.

I do provide a sample edit of the first ten pages of a prospective client’s work, so he or she can get an idea of how I work, and I think any writer deserves to see that kind of sample.

I read as far as “what you, the author, is trying to say . . .” and was stopped cold. Isn’t the subject there “you,” not “the author”? In which case, shouldn’t it read “are” trying to say?

Take away “the author” and you have “what you is trying to say.”

Good point, Jean, and well spotted. It just goes to show that all writers – even editors – need an editor.

On reflection, parenthetical dashes would’ve been better:

“what you – the author – are trying to say . . .”

Thanks for pointing that out Jean.

Kind regards,

Jim

Thanks for mentioning Linkedin Always room for one more resource.

I know a lot of people don’t like the idea of someone researching the internet for their background details, Gretchen, and I don’t think we have to go too far, to the point of looking into someone’s private life if you only have a working relationship, but I think it’s good to look at as many sources as possible to make sure you’re dealing with the right person to avoid – as Stanley mentioned above – those horror stories.

Thanks for your feedback, Gretchen.

All the best,

Jim

“That means more than simply adding some commas and periods – the editor also has to understand what the author is trying to say.

Unfortunately, that isn’t always clear from just reading the text. Where there are doubts about the author’s intention, the editor has to ask for clarification.”

That is so true, Jim. One of my editing clients is a writer from Nigeria. When I edited her first book there were some phrases that sounded awkward to the American ear, but I suspected were natural for Nigerian readers. The characters also sometimes did things that didn’t seem right for an American person, but I suspected those might also be what a Nigerian person would do. So I would e-mail her for clarification, and she was glad that I did. Now I am editing her second book.

Great article! I believe the right-fit developmental editor can be a great investment in a writer’s career. It was for me!

I learned so much from the one I hired. It was like getting a mini MFA. I learned things I had no knowledge about before like premise, voice, inciting incident, head hopping, dramatic imperative, expectations of genre, emotional moments, and more. I basically learned the structure of a story and filled my writer’s toolbox. This made me a stronger writer, and led to getting an agent and publisher – AND enabled me to know how to work with my assigned editor within the publisher. When she had comments, revisions, or concerns, I knew how to address them.

And I highly recommend my former editor, Kathryn Craft and WU contributor! https://www.kathryncraft.com/editing-services.html

But how to find a good fit? Asking your peers, doing research, reading reviews and testimonials, and asking to contact references. These can all help you find a best-fit editor.

This article is an answer to prayer. I am writing my first book and I have used an editor I met at a Christian conference & who developed a writing program at a university near my home. I have spent over $800 for him to put commas and other punctuation in, but absolutely no help for anything else. I’ve been wondering if this was the right thing to do and after reading your article, I now have the answer that I need. Thank you very, very much.