The Complex Power of Mapping the World of Your Novel

By Barbara O'Neal | April 26, 2017 |

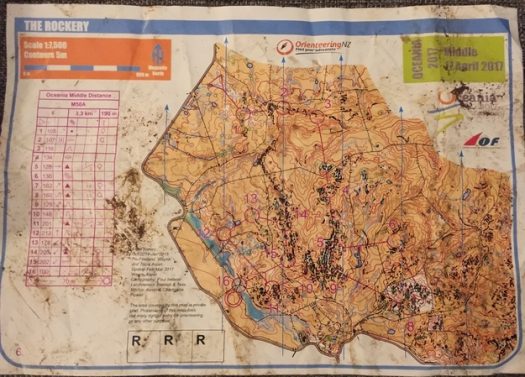

An orienteering map, covered with mud.

I’ve spent the past two days deeply engrossed in the mapping of my book world. First was a map of the landscape and town, complete with directional arrows so that I know which way the light falls. This morning, I’ve spent several hours making a very detailed map of a house and all the problems in it.

When I said something about those maps on Loreth Anne White’s Facebook page, she said she’d drawn her maps the day before. Alison Kent joined the map-crew by commenting, “I researched the police dept in the city I’m basing my fictional dept on, the number of patrol officers and detectives, authority ranks, etc., then drew the squad room and various offices and holding/interview rooms, and assigned cubicles to all my characters, naming all the new ones for going forward.”

I found it fascinating that we were all drawing maps in one way or another, that we needed that physical representation of the world of our imaginations.

My life the past five weeks has been deeply map-centric. I am in New Zealand with my partner, who is competing in the World Master’s games as an orienteer. It is the sport of using a paper map and compass to find a series of flags as fast as possible. The long courses are expected to take the elite of the group about 40-50 minutes, which means a lot of people spend much longer running around a forest, off-trail, getting scratched by hostile plants and tumbling down hills for the pleasure of getting all 15 or 20 controls, in order, faster than everyone else.

I’ve tried it. It’s really hard. Christopher Robin is a very, very good orienteer, a US champ. As you might imagine, he loves maps, and he loves setting up courses almost as much as running them.

The other map aspect of my life these past weeks is the fact that we’re navigating unfamiliar terrain. We have an apartment in the middle of the CBD, and over the course of weeks have learned where the supermarket is, and our favorite pie-and-pint shop, and the waterfront. We know how to walk all over the CBD now, but it took a week or two. We’ve also been walking and hiking, close by and farther afield, and because ferries are omnipresent in Auckland, I’ve been able to mentally map the various bays and gulfs and islands around. Not all of them, but some. Each time I pass Devonport now, I check in with it, and then Rangitoto, the volcano we hiked, which has a pale green, velvety little island right across from it.

Little by little, the map in my mind grows. You’ve had this experience, too, learning to navigate your neighborhood, your city, the area around a hotel you stayed in for a few days.

When Loreth, Alison, and I all posted about drawing maps of our book worlds, I suddenly wondered why do we do this? Is there something about the mapping itself that makes the work easier, stronger, better? Is there something in the human brain that needs this exercise?

Turns out, the answer is an emphatic yes.

The research on mapping and brains is very recent. According to Emily Badger in The Atlantic:

About 40 years ago, researchers first began to suspect that we have neurons in our brains called “place cells.” They’re responsible for helping us (rats and humans alike) find our way in the world, navigating the environment with some internal sense of where we are, how far we’ve come, and how to find our way back home. All of this sounds like the work of maps. But our brains do impressively sophisticated mapping work, too, and in ways we never actively notice.

Every time you walk out your front door and past the mailbox, for instance, a neuron in your hippocampus fires as you move through that exact location – next to the mailbox – with a real-world precision down to as little as 30 centimeters. When you come home from work and pass the same spot at night, the neuron fires again, just as it will the next morning. “Each neuron cares for one place,” says Mayank Mehta, a neurophysicist at UCLA. “And it doesn’t care for any other place in the world.” (https://www.citylab.com/tech/2013/05/were-only-beginning-understand-how-our-brains-make-maps/5678/)

One neuron, one place. One very specific place. Isn’t that incredible?

So, when I loop around the bays in Auckland, noting where Rangitoto is from the CBD and then from Devonport and then from Half Moon Bay, I’m actually building neurons that remember the locations for me, keeping me oriented in space. All those neurons continue to exist, even as others develop. When scientists at University College of London studied taxi drivers, they discovered that the section of the brain called the hippocampus was larger in the drivers, and the longer they’d been driving, the larger the hippocampi.

As with much of our knowledge of the actual working of the brain, these discoveries are very recent, most of it coming together only in the past ten years or so. Until this spatial function was uncovered, the hippocampus was mainly known as the center for memory. It is a portion of the limbic system, which regulates emotion.

This is where I found another intriguing connection—

Scientists now know that the hippocampus is both a map and a memory system. For some reason, nature long ago decided that a map was a handy way to organise life’s experiences. This makes a lot of sense, since knowing where things happened is a critical part of knowing how to act in the world. (https://aeon.co/essays/how-cognitive-maps-help-animals-navigate-the-world)

Why do we map the fictional worlds we are writing? I think we have a biological need to see the world we are creating, to create the markers over a landscape through which we can actually move. It’s more than needing to keep details in order. As I make a map of my imaginary world, I make it less imaginary and much more real by walking through it over and over, crossing the street to the bakery, walking around the medieval church (uphill, here, past the churchyard, where stones are worn smooth by time) and to the viewpoint where the open fields, soon to be planted with rapeseed, await full spring. On the horizon is the house, looking as it must have before it was a ruin. I create new neurons, real neurons, even if the map is of an imaginary world.

And because I’m creating neurons, I’m also connecting emotions to this landscape, to the place of my novel, both for myself and for the reader.

All of this underlines my long-held belief that sense of place is one of the most powerful parts of writing. Our brains are hardwired to be oriented, very intricately, to place, time, and thus, emotion.

Do you have experience with maps or have a ritual you follow when you land in a new place? Do you make maps of your landscapes?

And c’mon, isn’t this all just astonishing?

[coffee]

Great blog. I found the brain stuff particularly interesting — one neuron, one place? Wow. Makes me think of those people who wow those instant memory tests, where they have 2 minutes to memorize 100 things (or whatever.) One guy I read about said he remembers things by mentally placing them in a room in his house — in other words, a map.

I’ve always loved maps, and I also make maps of places in my books. When I was a kid, we moved often — 6 towns by the time I’d finished primary/elementary school (aged 11), and the first thing I did in each new town was walk all over it. I knew those towns better than my parents, who tended to stick to regular routes.

My mother moved a lot just as you did, Anne. I’ll have to find out how she feels about maps, and discover how she found her bearings.

One neuron, one place. This is potent and fascinating, and it explains our emotional connection to place in such a beautiful way. I’ve been making maps since I started my series of novels, at first to orient myself physically in a scene and choreograph action. Now I have a file full of place maps and diagrams of rooms, houses and even a schoolyard, and these maps have brought my world to life for me. In my story, there’s a concept put forth by one of the characters who comes from Ireland. The word, ‘ionndrain’, is actually Scots Gaelic, and refers to a longing and a deep connection to ones place of birth, and the feeling of loss when separated from it. This word, this meaning, hit me in a deep place, because not only is it beautiful, but I think it’s important, in out disconnected world, for people to have this feeling. If we, as writers, can help that to happen, then we are doing good work. Thank you for an enlightening and beautiful post. Enjoy NZ!!

Yes, One neuron, one place. One gobsmacking idea. I always make maps of my locations. big ones, little ones. Wall maps and notebook maps, maps of place and drawings of settings, distances between places. For me, it helps me stay lost in my story without getting lost by my story.

I know–it’s shivery. One neuron, one place. The brain is an amazing organ.

Fascinating stuff! I love maps, and I was tempted to connect my love of maps in relation to story back to Tolkien (an old refrain for me, I know). I loved referring to Tolkien’s maps of Middle Earth as I read (he drew them himself).

But my love of maps long predates my first reading of Tolkien. And I can clearly see the connection between map-making and emotion in my lifelong love of history. The house I grew up in was chock full of history texts and picture books, and I used to pore over the maps in them. I’ve always been drawn to old maps, too. I have a framed one of Michigan, draw in the 1600’s by a French cartographer who must’ve traveled the shores of the Great Lakes with the Voyageurs. It’s misshapen and the place-names have been varied or changed, but those things are central to its magic. The thought of charting an unknown, and often hostile, new world like that has always fired my imagination.

One of the first things I did when I started was draw maps, and now there is no way to know the extent of the impact that’s had on what I’ve produced. But I’m certain it’s profound. Thanks for connecting the dots in such a special way today, Barbara!

I love those old maps, Vaughn. One day, I’d like to take all the maps I’ve collected on my travels, and a bunch of Neal’s orienteering maps, along with some old and ancient maps, and cover a wall with them.

We travel a lot. When we built our home, I took any map that I had a duplicate of, pour coffee grounds or black tea on parts of them, set matches to corners, etc. – then I used wallpaper glue to put them all over the walls of a bathroom. Sometimes the light hits just right and a rainbow appears over Dublin.

When I travel, as I often do for work, I always bring or obtain a map of the place. Even more, though, once on the ground I want to know which way is north.

There are other kinds of maps, as well. The people I meet have maps of their lives, maps to happiness. The one map none of us has is the map to meaning.

For that we must start running with our topographical maps and compasses, never knowing where we’ll find the flags, but guided by the inner compass that can always orient us to north.

Love this post.

Lyrical as ever, Mr. Brinks. The maps to happiness, indeed.

I love maps and am sorry for people who claim not to be able to read them. Maps covered our living-room walls when I was a child. This news about the neuroscience of our sensitivity to space and maps is wonderful–thank you, Barbara! (And that is some rugged terrain on the orienteering map up top.)

Oh, yes, writing: if we use maps for our narratives, then our readers will always know where our characters are, what they can see from there, and what direction they are headed in.

I think that in most cases, people who can’t read maps simply haven’t been given the tools to do it. There are a few who just can’t process that information, but I’d bet that’s a relatively low number.

And yes, isn’t that rugged? I find it so intimidating.

Fascinating! I’ve been studying maps of story settings to orient myself and to help me add texture and dimension to my WIP. But this is so helpful in understanding the road (!) to adding emotion and a sense of place to the work.

As always, you bring such useful information to the table. Hope you’re enjoying your trip :)

Wow, Barbara! Fascinating stuff. Thanks so much for the post.

I love maps, both the real (especially the old) and the imaginary ones I draw, like the one on my wall of the city my current novel takes place in. How else would we (me and my characters) find our way? Nice to know I’m in good company :)

“I’ve spent the past two days deeply engrossed in the mapping of my book world. ”

Bang-on description of how I too experience drawing my book world or my garden landscaping. I experience working on maps or drawings to be a meditative state, a dropping into where things are in relation to each other. Which mountain ranges characters must traverse, the placement of rivers, creeks, or townships. The process is deeply satisfying. A bringing to life our imaginary worlds.

I believe in the importance of learning to map-read. Your fascinating post, Barbara, helps explain the sense of how we orient ourselves in our worlds.

Thank you!

I map my garden, too. Over and over, every spring, using the maps of the previous years to help me figure out what works and what doesn’t (dear Barbara, do not ever plant mint directly in the ground. Ever ever ever.)

I’ve seen alot of blog posts over the years about setting scenes, world-building, time stamps, etc. — all speaking to orienting the people and places in your writing. But your approach to this incredibly important aspect has topped them all!

Great work in tying everything together with science and common sense! I have been fascinated with maps since grade school, moving beyond road maps to topographical, and then to maps of rivers, oceans, bays, etc. — to maps denoting fault zones, volcano lines, and mountain ranges. The more we ‘map’, the more solid our view of the world we live in. Perhaps graphs and pie-charts showing statistics are an extension of our mapping urges?

Your partner’s contest doings sound exciting — must jump on the Google train and find out more now!

Thanks for sharing this fresh perspective.

Wow, this is a fascinating post! I haven’t *made* maps for my writing, but I definitely study existing ones, because so far I’ve only used actual existing locations in my fiction.

But I do love me some maps. While I’m starting to rely more and more on my phone for directions, I still like to get a “lay of the land” by studying an actual map. And I definitely use actual maps when planning long trips across multiple states.

When I first moved to Miami in the mid-80s, it was the largest city I’d lived in, and I was frankly rather intimidated, and wanted to know my way around. So I’d go for long drives when I had free time, armed with a map, and each day I methodically worked my way out further from my neighborhood. I don’t know where I got that idea, but it paid off: I got a good sense of my surroundings within a couple weeks of arriving.

When I moved to Los Angeles, my concept of what a map was got totally blown up. The LA metro area is so big that it’s impossible to capture in any detail on even a large fold-up map. So a friend of mine hipped me to the almighty Thomas Guide, a map that sliced LA into hundreds of grids, each of which had its own individual page in this spiral-bound book. During lean times, I took work as a courier, and drove all over LA County, and that book was a lifesaver.

I recently bought one of those big vinyl bound Rand McNally US road atlases, when planning a couple of long car trips. While during the actual driving we relied mostly on phone navigation, that atlas was still invaluable to me in conceptualizing our route during the planning stages.

Back to your post: The neuron stuff is REALLY interesting. That’s definitely making me think – I’d never consciously tied emotion to place the way you’re describing, yet much of my work seems to focus on characters trying to find their way home – or find their place in the world – either emotionally or physically. This is some marvelous food for thought – THANK YOU!

The research out there on this is pretty fascinating, Keith. I finally had to stop myself after a couple of hours and get to writing. SO INTERESTING!

Those paper atlases are great. I like paper maps in general, even though I do rely on my phone a lot more these days.

Creating maps of physical places can be very useful for us “backstage” when planning out stories, but I try to be cautious about referencing them too much when writing. Reading about a place is a very different experience from visiting it in person; relative positions and directions aren’t as important as they are in real life.

When a reader reads about a house, I doubt they construct detailed maps in their heads of where the living room is in relation to the kitchen, and whether the laundry room is by the garage or in the upstairs hall. They don’t memorize which minor character sits in which cubicle or whether the protagonist’s filing cabinets are to the right or to the left of her desk.

Yet I’ve read many boring descriptions cluttered with these minutiae, and many paragraphs of characters walking from the front door through the living room into the kitchen, up the back stairs and thence to the laundry room. Readers honestly don’t care. It’s enough to say, “When Bob arrived home, he found his wife in the laundry room.”

Yes. As with most research, what shows in the book is only the very tip of the iceberg. The reader will be oriented because we are oriented, and will draw a mental map of her own.

Thank you for writing this post and for including the research links.

Before I became a freelance writer, I worked as a cartographer. Computer software allowed me to map the locations of specific areas-such as taxing disricts, property boundaries, or agricultual lands. The digital maps were actually layers of information used for analysis. A map could be changed instantly by isolating specfic data. For instance, I could make a map of lakes by turning on a specfic data set and turning off others. It was a magical process. I could quickly change the fonts, colors, etc.

Mapping is a profession I absolutely miss. But I love writing more.

So mapping my novel’s world is something I did.

Being a cartographer would be enjoyable and creative, too. I did wander down one rabbit hole while writing this article that led to apps that allow you to use real life maps to create fictional maps. I had to stop after about an hour–some things would lead me to waste too much time.

Thank you for the interesting post Barbara.

I spent 5 years as a cartographer and land surveyor in the Marine Corps. These skills are being used in my SciFi stories now. I have a huge poster of a solar system I designed hanging next to my writing desk.

Maps are based on a mathematical model of the planet (like WGS 84) to account for the curvature of the earth. What I did in my story was to change that model in a drastic way in order to create a warped reality. My characters discover the worlds they live on are not what they appear to be.

Love that you knew enough to shift the mathematics to create new worlds. That’s amazing.

Oh how I love to learn new things. Thanks for the great post, Barbara.

I began mapping my story world out of necessity. In real life I’m ‘directionally challenged’. I don’t think my hippo is firing on all cylinders. I never know where I am and get turned around or lost easily.

Mapping the world of my novel was essential. Right now I have 4 different maps of ancient Babylon – one on street layout, one on canal and wall systems, one on building locations and one on topography. I’m so immersed in ancient Babylon that if it were around today I could walk you through it, show you where everyone lived, worshipped and worked, and take you to those secret places where all the bodies are buried, literally and figuratively.

To learn the brain science behind this need to orient myself in my story world is fascinating, as is the emotional tie-in you’ve emphasized. Perfect start to my writing session.

My brain maps many things. I reflected on this once when considering the days of the week. They form a ring in my brain and when it is Wednesday, I picture where that day is on the ring. I have a bigger one for the months of the year. I mentioned this once to someone–they thought I was a little crazy. Each to her own. Great post.

I have a similar calendar, Beth, and I see numbers like that, too. It’s a form of synesthesia, according to our writer Mama, Therese.

It’s true, it’s true! Here’s a little more info on ‘calendar synesthesia’ from New Scientist and Bustle.

I’ve loved maps since I was a child when I’d sit behind my grandparent’s couch and flip through old books. I’d study the maps within and imagine the places they represented, right down to traveling the roads. As a writer I make maps, lots of maps. I’ve made huge, complex maps of an entire continent, but also the seating arrangement around a dinner table. It’s important to know who can easily see who, who has to lean forward to make eye contact, and who can eavesdrop with ease.

Thanks for this post. And for sharing your current location. Sounds fascinating. Based on the science, I guess it’s no accident that so many of us put maps and nautical charts or “night sky” posters on our walls. The fascination with place and creating a story place never ends.

fascinating about the “place cells” and neurons! when I set my story world, I go to Google maps and find a town / location i like and “borrow” it. same with the houses or places they frequent (some not all). i’m an interior designer so i go all out and sketch a floor plan! and yeah, i know which windows get light and which ones not so much!

I love maps and doodling and I need to be grounded in a place before I can write but I had no idea why, so thank you for this wonderful post. Our brains are definitely amazing.

I can’t remember where I read this now, but research shows that doodling while listening also makes neural connections, so you don’t necessarily have to be taking notes per se. Typing doesn’t make those same connections. It’s as if we are transcribing while typing, whereas when we write or draw, we are synthesizing. So this whole map-making makes sense to me.

Wonderful post, Barbara. Like everyone else, I love maps. I kept thinking of the old ones that said “Here Be Dragons” at the edges. I think that not only expresses the terror we all feel at what lies beyond what we know, but the irresistible urge to explore it in our work, whatever that work is.

Fascinating. When writing my memoir, I drew a map of my childhood home and it unlocked a lot of memories so the hippocampus being both a map and memory system makes perfect sense to me.