How to Keep Readers Happy When Your Character’s Unlikeable

By Guest | January 22, 2017 |

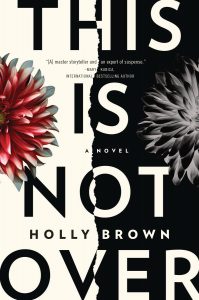

FUMIGRAPHIK_Photographist, Flickr’s Creative Commons

Please welcome Holly Brown as our guest today. Holly is the author of Don’t Try to Find Me, A Necessary End, and—just this month!—This is Not Over. In addition to being a novelist, she is also (in no particular order): a wife, mother, marriage and family therapist, poker enthusiast, resident of the San Francisco Bay Area, member of the SF Writers Grotto, lover of some incredibly shameful reality TV, devotee of NPR (she owes a debt of gratitude for inspiring more than one novel), and a believer that people should always be willing to make mistakes and always be the first to apologize for them. As a writer, she tends to be inspired by contemporary events and phenomena. She likes to take an emotionally charged situation and then imagine the people within it. That’s where her background in human dynamics comes into play, and where the fun begins.

I like unlikable characters, dammit! Always have, even before I was writing them myself, and they can always use a champion.

Connect with Holly on her blog, Bonding Time on Psych Central, and on Facebook.

How to Keep Readers Happy When Your Character’s Unlikeable

Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl broke the glass ceiling by allowing female characters to be as unlikeable as males have often been in fiction. For too long, women writers in particular were hamstrung by the need for relatability, which could lead to muted characters, dulled at the edges, your stereotypical women in jeopardy, more acted upon than acting. Here are some ideas on how to build vivid, complex characters who are as satisfying to read as they are to write.

First, a disclaimer: I like unlikeable characters. Generally, I like them better than likeable ones. That’s because I enjoy the challenge. With the most charming characters, it’s like, everyone can get into this person; there are no sharp edges for the reader to cut themselves on. But with the thornier characters, I feel just a little bit special for being able to get them. Or if I don’t get them, for being willing to engage in the quest to get them. And even if I never do, I was noble—well, entertained—in the attempt.

But not all unlikeable characters are created equal. There are some you want to pursue, and some you want to close the book and leave behind. While there are no hard and fast rules for characterization, and you don’t want to fall into tropes, I do notice some commonalities in the most compelling unlikeable characters. You might notice that your favorite unlikable characters possess one or more of these:

- They display intelligence or mastery, perhaps not to the world at large but only to the reader. We know what others in their universe do not, so it’s like we’re keeping a secret. Everyone’s attracted to people who are good at things, in fiction and in real life.

- They have a well-developed interior life. Again, what’s not visible to the other characters but only to us draws us in, and forward. Also, the dichotomy between what we know and what they show can be irresistible. It creates tension in every scene: Will they be unmasked?

- They have some elements in their backstory that provoke sympathy, empathy, or at least understanding, something that makes the reader think that similar circumstances could produce a similar outcome. “If I’d grown up the way they did, or lived through what they did, then maybe I, too…” It’s not exactly relatability, but it’s a kissing cousin.

They have charisma, perhaps of an unsettling type. It’s a quality that says don’t look away or you’ll miss something. As a reader, you want to know what they’re going to do next, and even if it would be implausible for the average person, it’s not implausible given that particular character’s psychological makeup and history. Every over-the-top action is grounded in that character. So they might be a train wreck, but they’re a very distinctive and unpredictable train wreck. We all like to be surprised, right? But best of all is when that surprise actually winds up feeling inevitable, like it couldn’t have gone any other way than it did, because of what the author so expertly created and set in motion.

They have charisma, perhaps of an unsettling type. It’s a quality that says don’t look away or you’ll miss something. As a reader, you want to know what they’re going to do next, and even if it would be implausible for the average person, it’s not implausible given that particular character’s psychological makeup and history. Every over-the-top action is grounded in that character. So they might be a train wreck, but they’re a very distinctive and unpredictable train wreck. We all like to be surprised, right? But best of all is when that surprise actually winds up feeling inevitable, like it couldn’t have gone any other way than it did, because of what the author so expertly created and set in motion.

I’m a therapist as well as a novelist, so I’m used to engaging with folks of all stripes. Some are incredibly endearing, right off the bat, and some are most emphatically not. I’m always honing my empathy skills, which is crucial for a writer. I’m also used to listening for emotional truth rather than literal truth, and that’s something that I think is especially important when it comes to writing an unlikeable character. Make them truthful, in their way. Make them consistent, in their way.

I write psychological thrillers, and if you do also, then one (or more) of your characters might be an unreliable narrator. The unreliable narrator can veer into unlikeability, running the risk of exasperating the reader. If he or she can’t be trusted, then it’s threatening to the relationship with the reader. The reader may, reasonably, ask: Why should I care about you, if I can’t believe you?

That goes to the heart of why I, personally, like unlikeable characters. Because I’m engaged even if I don’t necessarily believe. Because I’m interested in emotional truth, rather than literal truth. Because sometimes I think that emotional truth is all there is, in a given situation.

Now it’s about giving your reader that situation, and creating the corresponding character, an integration so well-rendered that like them or hate them, no one can stop turning the pages. With an unlikable character (the involving kind, that is), the character has to drive the plot; they’re inextricably bound. The things they do have to be connected to who they are. They’re not just stand-ins or surrogates; they’re richer and more complicated than that. That’s why when they’re done well, I love them the most—the ones I’ve written, and the ones I wish I’d written.

What do you like (or dislike) about “unlikeable” characters? Have you written an unlikeable character?

Thanks for the post, I love it! It seems that all I do is write about unlikable characters – no, let me rephrase that, not all my characters are unlikable but the ones I like best are decidedly unlikable and, yes, you’re right, they do drive the plot.

But I have found something amazing when I published in America (previously I had published in Italian and in Italy, a very different market). Many of my readers wrote saying they disliked my characters, on Amazon they gave me 4 stars instead of 5 (and some even less) because they disliked my characters – this happened again and again with one book in particular (Crimson Clouds) where they said the women in it were all nasty and the man (the central character and object of their attentions) was a…jerk – true, he was in fact the plaything of these nasty women. Of course, that was deliberate on my part, indeed, it was the whole point of the book!

But it didn’t go down well with my American readers, I could see that. So how does one get around this? I imagine you have the answers! I had called my book a “romance” but I guess it wasn’t, I must have drawn the wrong kind of readership. Should I have called it “literary”? But then, the book didn’t have the kind of literary veneer one associates with the literary genre. Can we call that un-romanced romance? Alas, there is no such sub-genre…So I guess I’m scr***d. Any advice?

That’s interesting–the cultural tolerance/acceptance of the unlikable character. Hmm, I do think that for romances, the readers are more insistent upon likability. Domestic suspense, which I write, is friendlier to it (largely because of “Gone Girl” and “Girl on a Train” and all the other girl books.) I also think that emphasizing the literary aspect can help, because readers are often comfortable with someone unlikable as long as they’re interesting.

How you label is so crucial to marketing, because it shapes the readers’ expectations. I’m not a marketing expert, of course, but those are my thoughts. Good luck!

Yes, genre and audience absolutely affect whether an “unlikeable” protagonist will fly.

My first book was a coming-of-age novel for young adults, and the heroine started out as a bit of a brat. She didn’t do anything wrong, but her personality was selfish, arrogant, and snarky. My teenage readers had an extremely negative reaction to her. They ranted at length about how much they hated her, and she was “the worst character ever in literature,” and her parents should’ve shipped her off to military school years ago.

Adults who read the book, on the other hand, praised the heroine’s characterization. They said the characters felt “real” and they chuckled to think about themselves when they were that age. But the book wasn’t written for these adults who liked it; it was supposed to be for the kids who hated it.

At first I pouted about the need to make my heroes likeable to please readers. Then I thought about it, and I understood why my readers hate unlikeable characters so much–they’re trying to live vicariously through them, and they can’t do that if they can’t identify with them. Now if I have a “point” to convey about the flaws of humanity, I do it through the side characters and villains. I can make side characters and villains as unlikeable as I want.

Holly, I too have had readers, primarily in the U.S. “complain” about the unlikable character in my novel. He is a narcissistic sociopath who is a yoga master and healer. He is brilliant, a gifted healer and can be exceedingly charming until he ensnares his victims – the women who are his clients. I agree with what you wrote above – This is not romance, which by literary definition has a happily ever after and the conversion of the “troubled man”. I do categorize my story as psychological dramatic fiction and I love your term domestic suspense! I also find UK and AU and other countries to be more welcoming – but then again Gone Girl and Big Little Lies did very well here. The first being called a Thriller and the latter I’d call Women’s Fiction due to the bonding experience of the women. Thank you for this brilliant article.

I agree. When dark protagonists appeal it is because they show strength, self-awareness and/or signal a longing for change. We will make allowances, and even enjoy, a bad protagonist when we have reason to hope that they somehow, eventually, will become good.

It’s a trick, and one that for me also explains the villains we love. For instance, and speaking of psychotherapists, Hannibal Lechter is one such. His goal is to plumb the depths of Clarice Startling, knowing her deepest emotional truth, and indeed he discovers her deepest wound and the meaning of “the silence of the lambs”. Upon escaping he assures Clarice that she is safe from him.

Sociopath? Yes, but buried in there (however unrealistically) is a heart. Deep down, unlikeable protagonists have about them something we can love.

Looking forward to This Is Not Over. Have a feeling I’m going to love it.

“We will make allowances, and even enjoy…”

I think your words are true for both ‘bad’ protagonists and well-wrought antagonists (Is there a more deliciously engaging villain than the uber-brilliant Hannibal?)

You mention sociopathy which I think is key. Among the dark characters that work best for me I find revelation of the individuals mental health pathology – both organic and experiential- as contributing to the “allowances” I make. It allows me to “understand” their damaged/twisted perspective and allows me greater engagement.

One character I had not thought of for a while jumped to mind – Lisbeth Salander. Not a Girl Scout by any means, but tremendously effective protgonist imo.

Thank you for the very interesting post and comments.

I do think that in real life, the vast majority of people doing bad things have some sort of underlying damage that drives them. So I agree–I like that in my books, too!

Hope you do enjoy it, Donald!

I agree that if you’re going to use a sociopath, they should have a heart (though I know some incredibly successful books haven’t bothered with the heart part. Honestly, those don’t tend to be my favorites, but I won’t name names because I don’t want to spoil the reveal for anyone else.)

Hi, Holly, Don & Tom:

So sorry I couldn’t respond until today.

First, Holly, I think this is an excellent checklist, and I’ve included it among my own files for teaching character. (I’m writing a piece for Writers Digest right now on the “Character of Crime,” and your post speaks succinctly and insightfully on several points I hoped to make.)

Specifically, the “well-developed inner life” element is something often overlooked. Readers do indeed enjoy being “in on a secret,” especially a dark secret. I emphasize secrets in my teaching on character because they automatically create depth — give a character a secret, there is now a difference between inside and outside, revealed and hidden.

One technique often used to enhance the sense of complicity — from Iago and Richard III to Frank Underwood — is to permit the unlikable character to speak directly to the reader/audience. For whatever reason, when the character speaks directly to us, even if he’s dishonest with everyone else (and ultimately even with us), we connect.

In fact, two books I read recently pushed this to the limit, one far more than the other.

Simenon’s DIRTY SNOW has perhaps the most unlikable protagonist I’ve ever encountered, and yet I couldn’t help but keep reading, precisely for the reason Don notes: There is the hope of change produced by insight. (He ends up not having the transformative insight — he explains his consequences in the same warped way he justified his wrongdoing, but the reader has the insight instead, a kind of “if only …” sense of reckoning.

The other was Jo Nesbo’s BLOOD ON SNOW (note the wintry theme here–it may be an homage to Simenon’s title/book), which has a hired killer protagonist. His appeal lies in several key elements: (1) again, we have access to his inner life, and get the sense he had a moral code; (2) he shows real compassion (and some longing) for the sister of one of his victims; (3) he demonstrates kindness, selflessness, and love. Because this is Scandinavian noir, the love is misplaced, but that only enhances the empathy. (And yes, his backstory reveals a truly relatable wound — but also a crime.)

I will take issue with the sociopath issue, however — this is a bit of a thing with me, so my apologizes if I seem to be mounting a soapbox.

I’m a firm believer in “Justify, don’t judge” your characters, and attaching a label to a character is a form of judgment. (Every woman writer I teach in LA inevitably as a “male narcissist” character, and I have the same issue with that.)

Giving the character an organic problem that creates their beahvior is a bit of a cop-out.

The character justifies what he does on his own terms — he is, as the cliche goes, “the hero of his own narrative.” Unless part of that narrative is an acceptance or even embrace of a condition that controls him, I see the “sociopath” tag as kind of lazy.

The key to making such a character compelling again resides in the realm of inner life — how does his worldview and sense of self serve to justify, legitimize, even normalize what he does in his own mind. Absent that, he’s just a robot with an organic disorder manning the controls. (And is he any more the product of his unconscious than anyone else?)

Wonderful post. Thanks so much.

David – just saw this reply so hope not too late.

Semantics are in play makingme unsure of the distinction you are making regards sociopathy and lazy. “Giving the character an organic problem is a bit of a cop-out.”

Indeed the essential aim is to reveal how the unlikable/villainous character sees their cruel/criminal actions as rational (in their reference) and justified. They are not cartoonish evil but pathologic in make-up via illness or what they have suffered (a great bar discussion of the fundamental nature of evil would be great fun).

I believe A knowledge of psychopathology can help the author create/reveal characters whose actions are “evil” but whose inner life supports their actions as justified/legitimized/normalized.

I certainly agree that Introducing a character, hanging a psychopath or sociopath descriptor on them, then revealing bad actions without any inner viewis not effective or emotionally engaging.

Creating a character where their thoughts and history reveal/support their uniquely disordered thoughts and world view can make the unlikable character understandable and compelling.

Sociopathy exists and is revealed via the character’s thoughts/actions. It need not be “tagged” though identifying a diagnosis is not necessarily lazy(eg Hannibal is labelled criminally insane yet it is our exposure to his thinking via dialog and interactions with Clarice that give us a glimpse of his complexity and somehow appeals.

What an interesting topic! I love the bad guys/gals – fascinating. Would love to discuss over cocktails.

Thank you for your post Holly.

It’s rare to see a post about unlikable characters and why we enjoy them as readers.

For me, the narrator of Jay McInerney’s Bright Lights, Big City is a good example of an unlikable character because they spend most of the story in a drug-fueled aftermath of a relationship. As Don said, it’s all a signal for wanting change in their life that doesn’t come until the last pages with the character realizing how superficial their ex really is. I understand (after reading your post) that what kept me going in that book was the intelligence and interior life of the character.

I’ll be adding your books to my TBR list for sure.

interesting post. Yes, I’ve written unlikeable characters and yes, they’re fun to write. But they weren’t main characters. I did not enjoy ‘Gone Girl’ and its bleak ending. Unlikeable main characters, for me, must change for the better, even if only slightly. I don’t care how well drawn the protagonist is, when at the end of the novel I’m left with a deepening sense of gloom and no hope, I’m dissatisfied.

The Bible has a verse in Proverbs – “Hope deferred makes the heart sick: but when the desire comes, it is a tree of life.” For me, that’s true. A life without hope is no life at all. I can be fascinated by a protagonist who I kind of hate, but at the back of my mind I’m always waiting, expecting that before the novel ends there will be at least a glimmer of hope that they will change for the better. I guess I’m an optimist and can’t help approaching all novels with this mindset.

That said, a good antagonist is equally important and you’ve given me plenty of food for thought in developing them so thank you!

Yes, there’s not a ton to redeem the characters in “Gone Girl” but for me, the quality of the writing is so high and the ride was so enjoyable that I was good with that. But I totally get when other readers aren’t. Charisma is important in your protagonists and your antagonists.

Great post, Holly. I, too, am very partial to unlikeable yet captivating and indelible characters, especially when they are the protagonist. It’s why I’m a big fan of such masters of transgressive fiction as Chuck Palahniuk, Bret Easton Ellis, Irvine Welsh, Hubert Selby Jr., and Craig Clevenger (who was kind enough to provide a testimonial for the back cover of my latest novel.)

Appreciating characters of questionable character, you might enjoy a recent tweet of mine:

“I’ve considered creating an utterly lovable protagonist, but I just know I’d hate him.”

Thanks for the nice Sunday read about not so nice characters.

Best of luck to you and your writing.

Regards,

GL

I do love that tweet, thanks!

I have a protagonist who’s a hypochondriac. He’s definitely not charismatic. His wife leaves him, he gets fired from his job, and he discovers a suspicious mark on his back in the shape of New Jersey. On the advice of a cab driver, he decides to behave as if none of it happened, which causes all manner of mayhem. I like him, but my beta readers don’t. I was told to give him a dog. Hmm.

After reading your post, I see how giving him mastery over something, or a richer inner life, could make him more appealing. Thanks!

I’m so glad that I could help solve one of your writing problems! We’ve all got those; it’s just figuring out the best way to counteract. Good luck!

Diane, your post made me laugh. “I was told to give him a dog.” As if owning an animal solves all ills! (Well, sometimes it does, but I cant imagine giving this advice unless pertinent to the story.) Write on!

Very interesting post, Holly – I especially liked the insight about the reader enjoying some sort of privileged understanding of the unlikeable character. I can’t help thinking of certain great Elizabethan villains, such a Marlowe’s Jew of Malta or Shakespeare’s Richard III, sharing their thoughts with the audience through asides, almost winking at us – so charismatic and captivating in their villainy.

That said, I once tried a historical novel with an unlikeable protagonist – an extremely intelligent young man, raised on resentment, and trying his hand at conquest with a good deal of success – and it was turned down consistently because of the protagonist. Perhaps mastery alone is not enough, and some charisma would help? You gave me food for thought – and a hope that that old story might be salvaged yet. Thank you.

Yes, definitely try to salvage! Nothing like scavenging from your own work and turning it into something new!

A provocative post timely for me right now. After receiving feedback to write out a nasty antagonist, I’m at a crossroads. Wondering if I should indeed do that, or scale her back. I am not afraid to admit it’s been fun as hell to get inside her lascvicious mind…BUT. It just may be she has to go to serve my story. I literally bought an adult coloring book, in hopes that a solution comes to mind as I wield the pencil. Wish me luck! And thanks for a great post!

Was the feedback to write her out entirely, or just maybe minimize her role? Hope you at least get to keep the juiciest bits! Definitely wishing you luck!

Darned if I don’t like my unlikable characters better, and sometimes even villains! Horrible, I know, but I do. It’s the same way in music; my favorite bands are damned big time.