There Is No Safe Place

By Lisa Cron | August 11, 2016 |

Imagery by Guy Billout; photo by Lisa Cron

I used to have this recurring image in my head. I was outside, on a deserted cobblestone street, in a very dim light, hemmed in by thick fog. I couldn’t see anything except gray. There was a strong current in the air – like a riptide. It was scary. I’d wrapped my arms around a thick concrete post, my feet having already lost touch with the ground. I knew with absolute certainty that if I let go, I’d be swept away. Not into darkness, but into . . . the unknown, and what the hell would I do then?

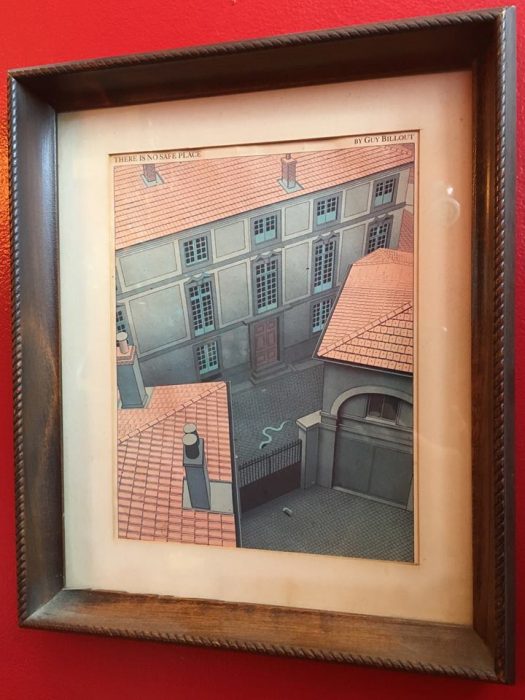

Holding onto that post made me feel safe. Then one day I saw a drawing by Guy Billout in Atlantic Monthly. It was of a cobblestone courtyard surrounded by brick and stone buildings. Fortress like. Impenetrable. Safe.

Except for a lithe green snake that rose and fell through the cobblestones as if they weren’t even there.

The caption was, “There is no safe place.”

For a moment I couldn’t breathe, because I knew it was true. And if there is no safe place, what was I doing standing still? And what, exactly, was standing still keeping me safe from, anyway?

That drawing liberated me. If it’s all a risk, if it’s all a challenge, why not embrace that, instead of a stupid post? I let go. And the amazing thing is that although it was really scary to let go — I’ve stumbled all over the place, and made a major fool of myself more times than I can count — it was scary in a good way.

Change is scary. All change. Even good change. Because it means leaving something familiar behind, and that’s hard, even when that familiar thing isn’t working for us at all. It’s why we stick with the devil we know. It’s not that we’re masochists (I hope), it’s just that we know the drill, and that makes us feel safe — even when we aren’t, even when that familiar drill is the very thing that’s keeping us from getting what we really want. The irony is that our “comfort zone” is often anything but comfortable.

My motto became: if it’s not at least a little bit scary, it’s not worth doing. I’m sharing that thought with you now for three reasons:

- I’m about to do something scary (for me), which is …

- … ask you to venture out of your comfort zone …

- … which might be scary for you.

So here’s the bargain I’d like to make with you: Hear me out. Read to the end. See if the change I’m suggesting is something you’re willing to try out.

What I’m proposing is nothing short of this: that you change how you approach writing, beginning with what, at this moment, you may think of as your innate “writing process.”

That’s a bold statement, I know. But given what a story really is, and what the brain is wired to crave, hunt for and respond to in every story we hear, there’s a good chance your writing process is kind of like the devil you know. Familiar, yes, but ultimately unproductive and given to questionable priorities.

You deserve better. Because you – along with every writer out there – are one of the most powerful people on the planet. Your stories have the power to change how your readers see themselves, the world, and what they go out and do in the world. And right now, let’s face it, the world needs a whole lot of help.

But in order to do that – to wield the power of story – there is one caveat: you have to actually tell a story.

Over the next several months here on Writer Unboxed I am going to take aim at the “writing wisdom” that often inadvertently leads writers so far astray that they can never find their way back to the story they want to tell. And in its place I will offer a clear, concrete and doable method of approaching story based on what actually hooks and holds readers (Hint: it’s not the beautiful writing or the “dramatic” plot).

But before we can talk about your writing process, it’s crucial to talk about what, exactly, rivets readers. To wit:

What Is a Story?

A story is one single unavoidable external problem that grows, escalates and complicates, forcing the protagonist to make a long needed internal change in order to solve it.

What your reader is wired to track, from beginning to end, is that internal change. And not track from the outside, but from within your novel’s command center: your protagonist’s brain. Story isn’t about what we do, it’s about why we do it. It’s not about what we say out loud, it’s about what we’re really thinking when we say it.

That internal battleground is where your novel’s seminal source of conflict stems from. It’s what gives meaning and emotional weight to every single thing that happens in the plot. Because – as I am very fond of saying – the story is not about the plot, the story is about how the plot affects the protagonist. And, in turn, the internal struggle drives the action, which then further provokes the struggle – back and forth – from beginning to end. That is how the external stakes steadily mount, stripping away every internal rationalization in the process, until, at last, the protagonist has no choice but to change (or, of course, not).

But, um, change from what to what, exactly? And while we’re at it, why does she need to change in the first place? As anyone knows who’s ever needed to make any kind of change at all (which is pretty much all of us), we’re aces at avoiding it for as long as humanly possible (sometimes even longer). Especially since the things we most need to change about ourselves, are often the very things we don’t see as problems at all, but as sustaining strengths.

And so – here’s the point – it takes a long time for that kind of defining internal problem to reach critical mass. It’s usually years – if not decades – before, at long last, the world finally forces us to get the hell up and do something about it, or else.

Or, if you’re writing a novel, before the plot kicks in, neatly catapulting your protagonist out of her (oft uncomfortable) comfort zone.

Here’s the skinny: All stories begin in medias res, meaning in the middle of the thing. The first half of the story is what creates both the internal and the external problem that the second half will solve. The second half? That is the novel itself. And here’s the kicker: most of what’s in the first half – the “before,” the “past,” yes, the “backstory” — will be laced into the novel itself, beginning on the first page.

This is why neither Pantsing nor Plotting work. There are myriad problems with both approaches, and they all stem from one seminal misconception: That the story starts on page one of the novel – that is, when the plot first forces the protagonist to take action – rather that when the story actually starts.

Pantsing Yourself into a Corner

We’re talking about the Just Do It! notion of sitting down, snatching up a pen, and writing forward by the seat of your pants. No forethought, no notion of where the story might go, or why. Because, the popular theory goes, if you’re a true writer – an organic writer – all you have to do is unleash your creativity and the story will come to you. In fact, pantsers are often told that knowing too much actually holds you back.

This is the literary equivalent of leaving your house for a year long trip with no idea of where you’re going, or how to get there, or what the point is, or what you’re leaving behind during that year, or even what kind of clothes to pack – which means you’re either going to be wholly unprepared, or are lugging around so many choices that you’re exhausted before you get to the corner.

While the euphoria of boldly launching into a brand new adventure might get you out the door, then what? When you get to that corner, do you turn left, right, plow straight ahead? The euphoria quickly wanes when you realize that since you don’t know where you’re going, it doesn’t really matter what direction you go in. After all, as Seneca the Younger so astutely pointed out a couple of thousand years ago, “If I man does not know to what port he is steering, no wind is favorable to him.”

Even worse, when a story hasn’t somehow appeared on its own after months of pantsing, writers are left to draw one conclusion: It’s my fault. I’m not talented, because if I was, this would be a story instead of a disjointed bunch of things that happen. Geez, guess it proves I’m not a writer. Let me reassure you that it’s not you, it’s the process itself that set you up for failure.

Now, let me say that I know that there are pantsers who do think about backstory, and who do, at times, pause to answer a question or two about their protagonist (or other character). Usually after the fact. Scattershot. In general. In bits and pieces. And that is not at all what I’m talking about here.

What I’m talking about is part of the story itself – the most foundational part, in fact. And it is not general. It is as specific as what you envision in the novel itself, and as fully developed. Without it there would be no problem, no necessary change, nor would the protagonist have an agenda when she steps onto page one (and we all have an agenda, every minute of every day). In other words, the protagonist would have no internal lens through which to view, and make sense of, well, anything.

Point being: We humans are wired to use our subjective past experience to give meaning to the present, and birth to our heartfelt agenda for the future (read: our dreams). The past is our hardwired decoder ring; without it we – and our protagonist — are nothing but a general facsimile of a generic person.

And there’s no story in that.

So if knowing nothing about the story you’re telling before you write it is a bad idea, then isn’t knowing where you’re headed part of the antidote? Indeed it is. And people in the second school of writing — the plotters – know this. The irony is, they then chart the exact wrong thing.

Plotting: How to Lock Yourself Out of Your Story

Like pantsers, plotters tend to begin on page one, and then zero in on developing the surface events of the plot, with no thought to the protagonist’s past, which is precisely what determines what will happen in the plot and why it matters to the protagonist. In other words, plotters put the cart before the horse, which does nothing but confuse the horse.

In this, plotters have made a very natural mistake: they have mistaken the plot for the story. After all, when you read a novel, what can you see? The plot, the things that happen: they’re concrete, clear and visible whether it’s a rip-roaring thriller or a quiet literary novel. So it’s maddeningly easy to tacitly assume that it’s a twofer: by creating a “dramatic” plot, you’ll also have a dramatic story. Not so.

This illusion is further fueled by the plethora of “story structure” manuals out there. Here’s how those well meaning guidebooks inadvertently steer writers wrong: they use very successful movies and novels as examples. Yeah, so? you may be thinking, what’s wrong with that?

It’s this: since we’re already familiar with these books and movies, we already know the inside story that the plot is there to serve. So when we examine the events in the plot, we know what they mean to the protagonist, and what they force him to struggle with internally, and so they have a juice, a power, that they wouldn’t have otherwise. This leaves the reader with the clear implication that by creating a plot that hits all the prescribed external points, in the right order, at the right time, a story will magically appear.

Again, not so. And again, this is not to say that all plotters pay absolutely no attention to the protagonist’s backstory. But – as with most writers – backstory tends to be developed in general, after the fact, in bits and pieces, maybe.

This is very different than actually developing the first half of the story: that is, the very specific, in-depth layers of the protagonist’s backstory that will be relevant to – and a major part of – the novel itself.

The backstory that I refer to is developed in the same way as the novel itself, often in full-fledged scene form. And yes, much of it is done before you get to page one. It’ll be used in the novel itself in the form of flashbacks, memories, thoughts, logic, supplying the real meaning of your protagonist’s fear and desire. These things are already inside your protagonist’s brain when she steps onto page one. They’re how she gets to page one.

I can’t say it strongly enough: This is not pre-writing. This is writing. This is how a novel gets developed.

Novels are not written in the same way they’re read – from beginning to end, all of a piece. Writing a novel is a frustrating, messy business – it takes grit, perseverance, determination, and the courage to go into those dark places inside that we often keep hidden, even from ourselves. It’s not for the faint of heart. But then, nothing worth doing ever is.

So – you may be wondering – how do you do it?

Become a Story Genius: Be a Seeker*

Pantsing and plotting are so ubiquitous that writers often assume it’s a binary choice – you’re either one or the other. Not so! There is another way.

You can be a Seeker, digging down to the seminal “why” behind everything that happens in the story, beginning with the moment long ago when something in the protagonist’s life forced her to embrace a belief that, while it rescued her at the time, has been leading her astray every since.

Because that belief – that thing she holds most true – isn’t. And so it becomes her defining misbelief. The story begins the second she embraces it, and everything else spins off of this one moment. It’s your story’s true north. It’s what will lead you directly to the moment – probably decades later – when the novel begins.

Next month we’ll talk about how to figure out what, exactly, you’re seeking, and then how to dig down to that seminal moment in your protagonist’s life, knocking over a few more writing myths in the bargain.

*Seeker. Hmmm. Not sure if that’s the right name for this new school of writing. Diggers, maybe? Divers? Someone suggested Plumbers, and then Pathfinders, and then Trackers. This is so fun! What do you think? [coffee]

Lisa, this post is so timely because I just started reading Story Genius. I admit I don’t spend enough time figuring out the main character’s internal struggle and goals before I start writing. It has resulted in a lot of angst and re-writing. Writers in general, and I am certainly guilty of this, tend to want to work out the story structure first. Like the reader we want to know what happens and so we figure out that piece of the puzzle first. But, as you say, without focusing on how the story events impact the main character, we just have a string of events without a purpose, or puzzle pieces that don’t make a puzzle. Like most writers, I also don’t write the back story before diving into the story. I have to try that with my current work in progress. Can’t wait to finish your book! Congratulations on publication.

Thank you, Lisa. So much to think about when crafting a story. I’ve done the combination of pantsing and plotting, and crafting backstory, then editing. Because I had the characters, then a plot but then I needed to figure out why it mattered to the main character and her antagonist. It has been extremely messy. I’ve enjoyed it and have also been frustrated.

I like your movement away from duality or forced choices into plurality, away from the either/or position into a digging deeper to find the unity that created the either/or.

Off the top of my head, other potential names:

Contextualists

or

Pre-storians

Pre-storians! Like that!

Marvelous! I’m always eager to hear what you’ve got next, Lisa, and this looks like the start of something big.

One thing that bugs me just a little: every writing expert out there seems to use the words “plot” and “story” but give them specific spins that are usually the keys to their visions. I love your definition of story as the internal change a protagonist goes through, and I hope when you bring this forward, you don’t let readers forget what makes your definitions different from all the others out there. Because everyone has their own “story,” and you’re trying to change that.

Can’t wait to see what’s next.

I like pathfinders. Has a historical flair to it. 8-)

I have a manuscript I drafted and revised a few times that’s been sitting in my drawer for a number of years. I definitely did built that story with the protag’s past life experiences in mind. Where it gets tricky is that we don’t consistently learn lessons from things that shaped us in the past and it can indeed take a long time to figure things out.

What that means for me as a writer is that since real life is messy, I struggle with the right ways for my protag to use those internal issues to solve the problem at hand because he’s torn in different directions. I wish real life were a decisive thing, that would make writing a lot easier. 8-)

Loved this post, Lisa. As for the name, I vote for pathfinder because writing is like following a badly marked trail. We set out on this journey full of enthusiasm, lose our way, backtrack or go around in circles, find the trail again and–if we have endurance–manage to drag ourselves to our destination.

As someone who has tried both “pants-ing” and plotting with varied results, I look forward to giving pathfinding a try.

Hi Lisa,

I started reading Story Genius on Tuesday and it’s already changed my perspective. Plot has never been a problem for me. The “stories” form in my head before I even put pen to paper (or fingers to keys). That’s what drove me to novel writing in the first place. Twice, I’ve written THE END and then had to go back and figure out my character’s emotional arc.

This time, on my new project, I’m starting with the arc. With your book and Scrivener, I’m going to build this novel in a novel way (sorry, bad pun.)

Thanks for the book.

Hi Lisa–

Your lengthy post today makes me think of what you recently attributed to Faulkner–that the past isn’t past, because it’s what we all bring with us in the present as we push into what comes next, the future. Isn’t that essentially what you mean about a novel starting long before the first page? Or, even more succinctly, “”What’s past is prologue” (Shakespeare’s The Tempest), i.e., everything that went before sets the stage for what’s happening or about to happen.

The takeaway for me in this brings me back to what is at risk of putting people to sleep by overuse: empathy. To write something worth the reader’s time, I have to succeed in inhabiting the lives of my characters. This is impossible without knowing what roadblocks they faced before stepping onto page one.

But in defense of all those of us for whom writing itself is the way we discover our stories, I offer the often-quoted words of Flannery O’Connor: “I write to discover what I know.”

Barry, I love this quote from O’Connor. So true! It’s all about discovery and each path is unique for each story.

All interesting thoughts, here, Lisa. I’ve written four novels and lots of short stories and every one is a struggle; I like that part actually, and I think it’s a necessary element in our creativity. As I read your post today, this comes to mind from author E. L. Doctorow (Writers at Work, The Paris Review Interviews):

“ I tell them [writers] it’s like driving a car at night: you never see further than your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way.” Doctorow wrote ten novels so I find his advice to come from not only his experience but also as an award-winning writer in the highest rank of American literature. He says that “Writing is an exploration. You start from nothing.” This makes total sense to me: being an explorer in the dark with limited light ahead but still climbing up the rocky terrain, because the journey to the peak is so worth it.

The name I would choose? Explorer.

Thanks for a stimulating post.

How about ‘archeologist’? That word came to mind when I was doing Jennie Nash’s Start-up last year. I excavated down thru all those already-existing layers and found my real story, many levels down!! For me, plot vs. story was a true revelation. It has changed the way I write for good and ever. I’m looking forward to reading Story Genius and having it in my arsenal when I start first-drafting book two. I also love what you said about ‘no safe place’- (love the painting!!). Reminds me of what Don Juan Matus told Carlos about death. Embrace it, he said. Make friends with it. Once you do, you can live with abandon.

Hi Lisa,

The book arrived yesterday. I’m rewriting my novel (funny, when I went to type rewriting it came out rewiring…) maybe reading your book that’s what will happen. The brain again, Beth Havey

I’m not sure your upcoming posts will change my approach to the process, because my process is already a lot like the approach you describe.

So, no fear.

Now, I’m not in favor of being a Plumber. Digger, Diver, Tracker…those sound forensic, which is perhaps not inaccurate but still a tad morbid. Pathfinder? Doesn’t ring for me.

How about Voyager?

It has a sense of going somewhere–and having come from somewhere, too. And whereas The Hero’s Journey focuses on a protagonist, The Voyager School of Storytelling focuses a bit more on the author. Just a suggestion.

Voyager is a good one, Ben. The others (Plumber. Digger, Diver, Tracker) sound mechanical and fiction writing is anything but mechanical. As for pathfinder—sounds like the generic voice on my GPS. :-)

And on those days you really jam, “Conquistador.”

Lisa,

Unlike Christopher, I’ve yet to get my greedy little mitts on Story Genius (I’m waiting until Salem) but I am rereading Wired for Story for a booster shot.

Backstory: the story behind the story. I’ve always subscribed to intense character study before ever writing the first word of a novel. Maybe my affinity for acting and theater has helped me hone that (or maybe a titch of OCD). Regardless, I realize the importance of backstory and flesh that out as much as I can beforehand.

As luck (or the universe unfolding in all its mystery) would have it, my actual sit down and write time over the past year has been greatly impeded by non-writerly activities. But all has not been lost. I’ve kept a notebook of all things concerning my wip — thoughts, notes, location ideas, timelines, snippets of dialogue, etc., but most importantly, the protagonist’s backstory (and a few of the other characters). This has led me to his defining misbelief. LOVE IT.

I’ve always considered myself a plotter, but now you’ve allowed me to see I’m really a seeker. I have to get down to the bones of every frikken thing — writing, life stuff — it doesn’t matter. I’ll chew a piece of gristle until all the flavor is gone and then chew on it some more.

My dogs hate me for that.

Thanks for your continued wisdom.

What do I think? I think you hit the nail on the head and the resulting ring is music. Pantsing and plotting are extremist’s diets where, yeah, this and that is true, but in the end you’re ill and abandoning what sounded like a good idea at the time. Of the names you floated I most like Pathfinders. In keeping with the other silly names should it be shortened to Pathers? Uh-oh. Perhaps Journeyers? Life is a journey and any tale is walking a stretch of that path knowing there’s more ahead and behind.

Lisa,

This offers hope. Plotter and panster rip me apart. I will bite this hook, out of frustration and with hope. Thank you.

Gretchen

PS: I vote Tracker

Pantsing doesn’t work? Tell that to Elmore Leonard, Stephen King, Tess Gerritsen, and even J.R.R. Tolkien. While I appreciate your fervor for your theories and methods, I don’t appreciate being told in no uncertain terms that my approach to writing is wrong. And to say that the *only* conclusion a pantser can draw if a story isn’t working is that “I’m not talented . . . guess it proves I’m not a writer” is ludicrous.

In art, I don’t think an “it’s my way or the highway” approach has much merit. It’s likely that your new book can and does offer insights that can help writers, and I was interested in it until this post came along. Now I wonder if it would be a waste of my time and money due to my untalented, wrong-footed, bass-ackwards way of creating a story.

I hear you! But . . . often good writers give bad advice, not on purpose. Here’s an article I wrote a while back that makes this point. https://composejournal.com/articles/why-good-writers-sometimes-give-bad-advice/. And for all you writers who are successfully pantsing or plotting, more power to you! You are part of the lucky few who have a natural sense of story — savor it. And feel totally free to disagree with me. All I’m suggesting is that those who don’t feel that their method is serving them well, might want to try something new. If yours is serving you — great!!!

How can anyone be successfully pantsing or plotting if, as you say, “. . . neither Pantsing nor Plotting work.”

I love this question, the answer is: some people have a natural sense of story — it’s built into their cognitive unconscious — they could write a laundry list and we’d be sobbing over the plight of poorly sorted socks. They CAN sit down, write, and for them, the story appears. I met an eleven year old girl in a small school district in New Jersey where I’d been brought in to help them incorporate story into how they teach writing, who had that natural ability. It blew me away. It is very rare. I do not think those successful very writers got to where they got to because they pantsed or plotted — they would have gotten there regardless their process.

The killer thing, I think, is that when those successful writers talk about their process it tends to be taken to mean that that somehow IS how they “got” their story, or a method for “finding” your story that anyone can use. For a very, very few that works. For most people, not so much.

I do think, for most people, pantsing and plotting leads you away from what matters rather than to it.

Regardless one’s process, my mission is to help writers focus in on, and dig down to, what it is that really rivets us, and then get that onto the page.

“Feel totally free to disagree with me.” This is not directly a disagreement but there is a point that goes beyond pantster or plotter process. I see you say ‘it’s the process itself that set you up for failure.’ But isn’t the creative writing process uniquely personal to each and every writer? May I cite Doctorow once more? He advocates discovery of *your own process* and the value of failure.

E.L. Doctorow: “One of the things I had to learn as a writer was to trust the act of writing. To put myself in the position of writing to find out what I was writing. With Daniel [The Book of Daniel] I wrote a hundred and fifty pages and threw them away because they were so bad. The realization that I was doing a really bad book created the desperation that allowed me to find its true voice. I sat down rather recklessly and started to type something almost in mockery of my pretensions as a writer—and it turned out to be the first page of The Book of Daniel. What I had figured out in that tormented way was that Daniel should write the book, not me. Once I had his voice I was able to go on. That’s the kind of struggle writing is.” [https://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/2718/the-art-of-fiction-no-94-e-l-doctorow]

This is a classic example of the pantster “discovery” writing process producing successful results; no doubt plotters have equal accounts of success. I find the most useful writing advice—not from writing instruction books or teachers—but from fiction writers who have plenty of first-hand experience writing fiction and know what it is to sit down and create characters and imagine stories in hundreds of pages. Would you agree, Lisa, that the best writing process is not one-size-fits-all, exclusively one way over another, but instead exists within the each writer, within his or her own honest creative process in the act of trust?

Well, I agree with you.

Thanks, Ray. :-)

Great post. I like the name Deep Within

I’d love to increase my ratio of published to unpublished manuscripts, which now stands at 2:6. Which is why I’ve already bought a copy of STORY GENIUS.

Thanks for this post, Lisa. I love the way you talk about story. Your definition and insights about what came before are awesome no matter what process we use. And, as discussed in this recent post, sometimes it’s good to try a different process and see how it works for you.

https://staging-writerunboxed.kinsta.cloud/2016/07/30/on-the-road-to-a-rough-draft-if-you-dont-know-where-youre-going-any-road-will-do/

Amazing post … which means I can’t procrastinate from writing my real story to write an obsessively long comment. And here’s why I do that:

“Change is scary. All change. Even good change. Because it means leaving something familiar behind, and that’s hard, even when that familiar thing isn’t working for us at all. It’s why we stick with the devil we know. It’s not that we’re masochists (I hope), it’s just that we know the drill, and that makes us feel safe — even when we aren’t, even when that familiar drill is the very thing that’s keeping us from getting what we really want. The irony is that our “comfort zone” is often anything but comfortable.”

Writing the Story Genius way is really, really hard for me … and painful (In a great and rewarding way). To go deep into the characters means I have to look deeply within myself … to find the core of the story … I have to jab my fingers into my own soul and rip it out and observe it, trying to understand what triggers me, what scares me, and the things I love and treasure more than anything in the world … the things that make me WANT to live… And that’s because “Story isn’t about what we do, it’s about why we do it. It’s not about what we say out loud, it’s about what we’re really thinking when we say it.” How can I do this with my characters if I can’t understand it in my own self? That’s what makes this process so hard and so scary … because I can’t fill a page in the way that I need to if I didn’t go deeply within my own soul.

Why do my husband and I continue to poke fun at each other, fight, and just sluff off the emotional jabs? Even when we both agree that we don’t want to anymore? Because we’re afraid of kindness and love and emotional attachment? Logically that sounds stupid. But what if I am kind, which makes me emotionally vulnerable and then he ‘steps’ on me … hurts me … and now I will feel the hurt because I’ve let my wall down in order to show love … These are the things that go into my characters because these are the things we all deal with on one level or another … especially those who are shaking their heads ‘no’ right now. One of my neighbors told me she had a perfect childhood and no one yelled or said anything mean … She offered me a glass of wine and I kindly said I don’t drink … she started stammering, saying that she and her husband rarely drink and only did so at parties … as if I was judging her when I was not. I just don’t drink. It was so interesting to me as to why she was acting this way that I instantly wished I could be in her head. This for me is story (because we can be in her head) and why I choose to trust the Story Genius.

Oh goodness, yet another long comment. Wow the brain can sure procrastinate. I’m buying you a very large coffee!