Everything I Need to Know about Dialogue, I Learned from Aaron Sorkin

By Dave King | February 16, 2016 |

Man imprisoned for beating his wife: You look down on people.

Will McAvoy: Down is where some people are.

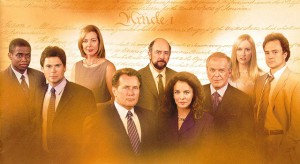

I came across that delicious line while Ruth, my wife, and I were watching what is, sadly, the final season of “The Newsroom,” the HBO drama produced and largely written by Aaron Sorkin, who was also responsible for “The West Wing.” Both shows are a continuous feast for someone interested in quality dialogue. It’s not just that the Wikiquotes page for “The West Wing” is huge. If you compare it to the Wikiquotes pages of other popular shows, you find that the other shows quote moments when the plot changes direction or the characters make a key revelation. Most of Sorkin’s quotes are simply there for the originality of the language.

So how does he do it? How do Sorkin’s characters manage to constantly say things that are so sharp and memorable? What makes his dialogue as good as it is?

First, it’s dense. Sorkin’s characters often speak one or two lines that summarize remarkably complex thoughts. In the example above, Will could have argued that claims of elitism are often a defense against deserved public condemnation. He could have said that the egalitarian ideal doesn’t mean that all people are morally equal, and there’s no reason to pretend otherwise. Instead, six words, five of them single-syllable, say everything he needs to say.

Or consider this confrontation between Toby Ziegler and a congressman, from “The West Wing” – since it is such a rich source and more easily available, most of my examples will come from “The West Wing:”

Toby: You’re concerned about American labor and manufacturing.

Congressman: Yeah.

Toby: What kind of car do you drive?

Congressman: Toyota.

Toby: Then shut up.

Of course, brevity isn’t a virtue in itself. Certain characters should be allowed to ramble on, because that’s who they are. Most of Sorkin’s characters from these two shows are journalists, speechwriters, speechmakers – people who make their livings by saying complex things in simple ways. The density of the dialogue fits their characters.

Other characters, who don’t make a living with words, speak dialogue that’s a bit looser. Josh Lyman, for instance, is the Deputy Chief of Staff on the West Wing, a job that is much less dependent on an elegant command of language. (Josh once described his job as, “The President doesn’t hold a grudge. That’s what he pays me for.”) Here’s Josh describing a disagreement. “You know what this is like? This is like The Godfather. When Pacino tells James Caan that he’s gonna kill the cop. It’s a lot like that scene, only not really.” When Josh loses control of a press briefing, here’s how he explains it to President Bartlett.

Bartlet: You told the press I have a secret plan to fight inflation?

Josh: No, I did not. Let me be absolutely clear, I did not do that. Except, yes, I did that.

Of course, good dialogue demonstrates character in ways beyond how wordy or brief it is. A character’s dialogue also reflects their education, their history, their concerns. Consider Charlie, President Bartlet’s “body man:” a combination of valet, personal assistant, and general gofer. Charlie was a high school graduate, raising his younger sister, when he first got the job, and was not used to moving through the corridors of power. Throughout the series he remains quietly deferential, even when the people he’s dealing with are being difficult. When an arrogant and unwelcome White House visitor demands to see Charlie’s supervisor, Charlie replies, “Well, I’m Personal Aide to the President, so my supervisor’s a little busy right now trying to find a back door to this place to shove you out of, but I’ll let him know you’d like to lodge a complaint.” Or this exchange, when Charlie had to wake the president in the middle of the night:

Bartlet: Charlie, do you realize you are committing a federal offense right now?

Charlie: I’ll take my chances with the feds, sir.

Bartlet: How do you know the First Lady wasn’t going to be naked when you came in here? Come to think of it, where the hell is my wife?

Charlie: Argentina, sir.

Bartlet: Oh, yeah.

Good dialogue doesn’t simply show who the characters are, it shows how they relate to one another. Consider this conversation between Josh and Donna, his personal assistant — who, in her gentle, Midwesterner way, refuses to take him as seriously as he takes himself. She has just made an emergency flight reservation for him.

Josh: And I don’t have to change planes in Atlanta?

Donna: No, even better, you do have to change planes in Atlanta.

Or this exchange, from later in the show’s run.

Josh: You used to love it when I couldn’t dress myself without you.

Donna: I used to love peppermint ice cream, too, but now those little pieces of candy, they get stuck in your teeth in a way that I find irritating.

So how do you do it? How do you get your characters to use language that reflects their personalities?

Even though you’re aiming for character-driven dialogue rather than simple brevity, the two are related. Most of what fills out bad dialogue is linguistic chaff – generic phrases, stock responses, speech without thought. Once you winnow this out, you will not only have something more succinct, you’ll have something more authentic.

I’ve suggested this exercise before, but it’s worth repeating. Gather all the dialogue spoken by each of your major characters into a separate file, and read it all together, all at once. This lets you focus on the language itself without the distraction of how the dialogue advances the plot. How much of what your characters say is generic? I’m not saying you should get rid of every ordinary, stock phrase – they do play a role in conversation. But if you have a lot of bland, ordinary lines, start cutting.

Now look at what’s left. How much of it shows a unique voice? And how distinctive are the various characters’ voices from one another? If you can’t see a character’s history, education, fears, and desires in how they use language, then you have to get to know your characters better. You might try writing key scenes from the point of view of different characters, which forces you to think from inside their heads, to focus on what they want from the scene.

As you do the exercise, keep an eye out for clichés as well. You will rarely find them in Sorkin’s dialogue – most of the metaphors used are fresh. Take this “West Wing” line, said by a Republican attorney to a Congressman who was about to engage in an unfair, and unfairly partisan, attack. “And if you proceed with this line of questioning, I will resign this Committee and wait in the tall grass for you, Congressman.” This image of a patient and relentless hunter is instantly recognizable and visceral, yet I’d never encountered it before.

Or there’s this quick exchange, in which Leo, President Bartlett’s chief of staff, is talking with Toby about how to convince Bartlett to run for a second term.

Leo: Toby, if you knew what it was like getting him to run the first time . . .

Toby: I know.

Leo: Like pushing molasses up a sandy hill.

Even when clichés show up, Sorkin often gives them an original and surprising twist. Take this line, spoken by an election operative to his staff. (Warning: slightly NSFW). “We will work hard, we will work well, and we will work together. Or so help me, mother of God, I will stick a pitchfork so far up your @$$es you will quite simply be dead.”

Or there’s this, from a discussion about how to present a couple of possible Supreme Court nominees to President Bartlett. Note how the cliché is allowed to hang fire a moment before Sorkin circles back to blow it up. “We bring Christopher Mulready in. We bring Lang back in. Hopefully the two of them woo the pants off the President, and he agrees to the deal without noticing he’s standing in the gaze of history, pantless.”

As with generic phrases, you don’t necessarily have to weed out every cliché. They are sometimes the best way to say something. Even when they aren’t, people often use clichés in real life, so an occasional one gives your dialogue verisimilitude. But if a particular passage is flat and flabby, look closely at how much of it follows the well-trodden path. If you’re finding a lot of clichés, cut them and look for something better.

As I finish writing this, Ruth and I are going to watch the last episode of “The Newsroom.” It’s all right, though, since we’ll probably watch the series over from the beginning – we’ve seen “The West Wing” at least twice now. And we’ll probably spot new and better examples we didn’t notice last time.

[coffee]

Dialogue is the very best part of writing.

In real life, you say something – and then wish later you’d said it better, or pithier, or with a bit more panache and a wink.

In fiction, you just go back and put that in.

Dialogue is why I loved Justified. And Firefly. And the West Wing.

And why couldn’t we get Martin Sheen to run for President again? He hasn’t actually done it yet, so the term limits don’t apply.

I’d vote for Martin Sheen. I have to re-watch the show now. I was kind of mesmerized the first time around. I love what you said about cliches here, Dave. Sometimes they just work, especially when you put a twist on them that fits the speaker’s personality. Thanks for a great post.

You’re welcome. And by all means watch the show through again. The first time through, you can’t help but focus on the drama and the characters. It’s the second (or third) pass that really reveals the beauty of the mechanics.

As to president Bartlett running again, remember that Sorkin gave us Santos, a minority candidate with great integrity and vision coming out of the Senate and beating the presumptive nominee, then, after he was elected, appointing his greatest political rival to a major post.

It all sounds hauntingly familiar, no?

That’s the beauty of great writing. It mirrors us, shows us what we are, and hopefully, what we could be. I agree about the benefits of re-watching these series. I watched Out of Africa once just to check out the hats.

For the first few lines right from my email I was picturing Alan Arkin, and it didn’t stop me from continuing. Maybe there’s another article in that.lol

And I experienced something very different reading this post. You see plot, back story, conflicts, story arc, outlines, editing, resolutions, generally anything but dialogue feels like a foreign language so I’m reading for learning. But dialogue — I get. When I read your words I just agree. Thanks for a few seconds of validation. Love WW, will now eagerly anticipate The Newsroom.

If you haven’t seen The Newsroom yet, you’ve got a treat ahead of you. It grabs your attention right from the start with another Sorkin technique that I didn’t mention — epic monologue.

Warning, this is an HBO show, so adjust your expectations about the language accordingly.

When my daughter and I had political jobs–each at a high-level, but different, site–we’d commiserate that no one walked the corridors speaking with the wit of West Wing. I’ve watched all episodes twice. Thanks for nudging me to view them a third time.

Even before I became an editor, I read favorite books several times — I think I’ve gone through Watership Down five or six. It was how I first learned how stories work. If you know what’s coming, you can pay attention to the mechanics of how it gets there.

So, yes, hit The West Wing a third time. It’s worth it.

Nice piece, Dave. Indeed, strong dialogue is the key to enthralling writing – and something so many novice writers struggle with. And agreed, nobody on small or big screen does it better than Sorkin.

Newsroom was fantastic and sadly seeming under-appreciated. Have zealously followed and been amazed by all Sorkin’s efforts on small (Sports Night was also terrific and also under-appreciated, West Wing, Studio 60, all great. And his movies never fail to resonate.

From small character driven discourse to dealing with big-issues, Sorkin-crafted dialogue always is powerful, pithy and punchy.

I love his dialogue. His are shows that you can’t multitask while watching. Your full attention is required or you’ll miss something in the rapid-fire dialogue. He uses a lot of the same lines in different shows, but it always works! Thanks for reminding me of his way with words.

“Gather all the dialogue spoken by each of your major characters into a separate file, and read it all together, all at once. ”

This is the first I’ve seen this advice. It sounds so daunting, but I’m definitely going to do it. The idea made me blanch and get excited at the same time.

Thanks for the suggestion, and a great article! I confess I have never seen the Newsroom, or The West Wing. I guess I have some things to add to my Netflix list now!

I’m actually surprised this advice hasn’t come up elsewhere — I was afraid I was unconsciously plagiarizing someone. It seems like a natural way to isolate how each character uses language.

As Will McAvoy says in the above clip, the first step in solving a problem is recognizing that you have one. If you do have a problem creating distinctive character voices, gathering your characters’ dialogue together can alert you to the problem.

Thanks for another great post, Dave. I love your idea of making a separate file for all your main characters’ dialogue. Another one for great lines of dialogue from “The Newsroom” and “West Wing”.

You really knocked my socks off, and that’s hard to do in mid-February in the Great White North.

A great article, one that gives abstract theory, concrete examples and a practical exercise (one I’d never heard of before and I already love.) Thank you!

Great ideas in this post. Will save and thank you!

The other day I was reading just that – all the dialogue from one of my historical novels. Then I came upon an ‘information dump’ where I wanted the reader to understand about dressage; and it’s one of the best bits of dialogue I’ve written. I’d like to dump a few lines of it here, and beg your comments…

Set the scene – a cavalry officer is preparing the German equestrian team for the 1936 Berlin Olympics, but is stretched for time, and asks his new ADC to help…

***

Anything I can do today?” Paul Adler leaned through the door.

Erich snapped awake. “Do you ride?”

Paul sauntered inside, a cocky smile on his brash young face. “Of course I ride, sir.”

“How are you at dressage?”

“Dressage?”

“Dressage. You’ve heard of dressage?”

“Oh sure, sir. Namby-pamby dancing on horseback.”

Erich stared at him, astounded. “Dancing? Are you aware of the purpose of dressage, Lieutenant?”

“Purpose?” His imitation of Erich was more echo than impudence. “Looks tedious to me, sir, if you’ll excuse me. Ride into an arena, five paces here, six paces there, shoulder in, shoulder out, stop and start, salute the judges and leave. Every horse exactly the same as the last horse. Oh, I’ve seen a competition or two, no idea how the judges mark them, they’re all exactly the sa—” He shut his mouth abruptly, as if only now he’d noticed Erich’s face. “Sorry, sir.”

“I take it you could not possibly school my horse for me.”

Paul laughed.

“Didn’t you know,” Erich said quietly, “that dressage is the highest form of precision horsemanship ever developed? Perfect coordination between horse and rider? Instant response to the slightest shift of weight, signals not even visible to the judges? If they catch you, they mark you down?”

“What’s dressage to do with the cavalry, sir? You ride into battle and the horse gets killed.”

Erich looked helplessly up to the ceiling and sighed.

****

Oh, and I too love The West Wing. I have the whole thing on disc. I shall watch it again.

That is effective dialogue, using the minor tension between the two characters’ worldviews to convey the information.

Just one quick observations — I’m sorry, I can’t help it, I’m an editor. Note how often you describe a character’s emotion in the brief passage — “cocky,” “astounded,” “helplessly.” Try cutting them and finding a way for the dialogue to convey the emotion.

Not that I’m in Dave’s league in the editing department, but I’d say this was all very well done until you get to “Didn’t you know…” which starts to turn the whole exchange into an “as you know, Bob” moment for me.

Since you put it out there for feedback… . Hopefully I’m not coming across as snarky. : )

I can see your point. And as I always tell clients, your mileage may vary. But for me, the tension between the two men kept the exchange from becoming a simple information dump.

Lyn, I hope you don’t mind that we’re poking at the example you put up. I’m afraid it is a bit of an occupational hazard with me.

But Dave, that’s why I put it out there. We all need an independent set of eyes.

I shall go back and check the comments with the text.

—

Okay, I’m ba-ack.

I deleted ‘astounded’ and ‘helplessly’. Both are conveyed by the dialogue as it stands.

I did not remove “Didn’t you know…” because it conveys (to me) the strained patience of the senior officer.

I left the description of the ADC because, as a minor character who is only incidental throughout the novel, I wanted the reader to get an instant picture of a brash young man.

Thank you both for your comments.

Here’s a link to Will’s speech on why America isn’t the greatest country in the world anymore — from the missing clip above. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q49NOyJ8fNA

Great post, Dave. Always loved West Wing, and Sports Night was another favourite. I’ll have to give Newsroom another try. I find Sorkin to be a little more obviously self-aware about his great writing in the first couple of episodes and it didn’t come across as well for me. Above noted clip was an exception.

I will definitely try your dialogue tip.

As you read through the comments, note how many of you were already aware of Sorkin’s gift for dialogue. It really is remarkable.

But I’d like to expand the conversation here. Why is Sorkin’s dialogue so good? I’ve hit some of the major points in the article, but there is still much more to say. For instance, I thought of including a paragraph or two on how his characters listen to and respond to one another. Or how his characters often answer anticipated questions, essentially leaving out a few lines of what would be more mundane dialogue.

So I’d encourage you, go to the Wikiquotes page I linked to at the head of the article. Look over the best of The West Wing dialogue. What makes it work for you.

Oh I love this, so helpful and I loved NEWSROOM and WEST WING and Aaron Sorkin. But examining dialogue and using the methods you describe here is brilliant. And who wouldn’t want to rewatch those fascinating shows to get a grip on better dialogue. You made my day.

Don: Oh, you’re saying that I’m not pithy enough?

Dave: Delete “that” and “enough”.

Don: Cut it out! That’s enough of that!

Dave: Right.

Outstanding post, Dave. Pithy, rambling, revealing…no matter what the strategy, in manuscripts authors frequently just let the dialogue spew with little attention to effect.

In workshops I use a similar exercise to your isolation of dialogue. It strips out attributives and the clutter of incidental action. I then have writers turn make the dialogue rat-a-tat, a speedy back-and-forth. That cuts out unnecessary words.

For the most part I find that punchy is best. Rambling is great for effect and to reveal character, as you say. Trouble is, many writers have it the other way around.

Okay, I laughed out loud at your opening.

Arguably, rambling dialogue that actually captures character is as hard to do as humor. You’re right that most of it is less rambling than padded and flabby — the opposite of character-driven — and punching it up is an improvement. Also, I love your technique.

It might be worth looking at people who do it well. I almost included examples from Dorothy Sayers’ Dowager Duchess, from the Lord Peter Wimsey books. She often speaks entire paragraphs of surreal stream-of-consciousness ramblings that are unique and instantly recognizable. It’s really a remarkable achievement. Unfortunately, I couldn’t track down a good example in time to get the article up. I should dig the books out of the attic and track a good example down.

In every movie or TV show I watch, it’s the dialogue that catches my attention…or doesn’t. Since I write YA and middle grade, where there is little patience for long description or narrator intrusion, dialogue is especially important. The trick is making a 13 year old sound witty without making him sound thirty years older. But if you listen to kids, they come up with some interesting illustrations. Dialogue is my favorite part of writing. Probably why I love writing for kids!

You’re right, making your dialogue age appropriate is another, interesting set of challenges.

This is a fantastic post! My husband and I have watched The West Wing all the way through twice, and I agree that the dialogue is fantastic. (I’m adding The Newsroom to my mental list — haven’t seen that yet.) Your examples were really well pulled, and your analysis. I love the idea of taking each character’s dialogue and putting it back-to-back in a document to look at on its own. That’s really smart; I’m definitely going to try that.

Hi, Dave:

This is an excellent example of a simple truth: You learn to write strong dialogue from writers, not people on the street. Though this dialogue is “heard,” it’s also written, not off-the-cuff speech. Our best teachers of dialogue are those writers who do it well. My personal mentor is Richard Price, but Sorkin is particuarly impressive in how he makes complex ideas sound like something rolling off a person’s tongue. He really is one of the best.

Not that he doesn’t have a few quirks and tics of his own. I’m sure you’ve seen this: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S78RzZr3IwI

Great post. Thanks for the great quotes and the excellent guidance.

I hadn’t seen that video, no. But given the man’s output, some repetition isn’t surprising.

And it’s interesting that Price is a screenwriter in addition to being a novelist. I suspect that screenwriting, where the dialogue carries so much of the story, may impose discipline on writers that forces good dialogue.

David – beat me to it. The supercut is great, and pretty hilarious.

Oh hell yes. You had me at “Sorkin.”

Best. Dialog. Ever.

I finally had to stop watching West Wing because I pretty much have the entire series memorized, I’ve watched it so many times. It’s been a HUGE influence on me as a writer, as have his other shows: Sports Night, The Newsroom, and the catastrophically badly titled “Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip.”

I love his dialog even when his characters are speaking badly. A favorite moment is when Toby is afraid of a vote he’s waiting on being jinxed by premature celebration, so he chastises an overly optimistic colleague by saying “Do you want to tempt the wrath of the whatever from high atop the thing?” On the page, it looks ridiculous. But watch this scene, and see how perfect it is.

You’re right, that is a brilliant bit of dialogue — and example of a character not being witty in a way that fits with who they are. There was a scene in “The Newsroom,” (third season, first show, if I remember right) where Will gets into the middle of an inspirational monologue, completely loses his way, and says, “What am I saying?” It was a fun moment.

Let’s take on one of those additional paragraphs I mentioned — Sorkin’s use of monologues. If you listen to Will McAvoy’s monologue in the clip I linked to earlier, you’ll note that Sorkin manages to convey an awful lot of information in a hurry, building a complex argument on an array of facts. Yet it doesn’t feel like the story has slowed down at all. In fact, this was the first scene of the series, and even though I’ve seen it several times, I still find it inspiring and riveting.

So here’s another exercise for you. How does he do it?

If you would prefer an example of a Sorkin monologue that has more G-rated language, try this one, from the first presidential debate between President Bartlett and the governor of Florida.

Enjoy. And game on.

Dave, intriguing tactic to isolate the dialog of characters in a piece—in looking at the speech of the two principle characters in my WIP, they don’t have any problems with cliché. More likely, they have problems with sounding too witty at times, in different ways. One’s an elliptical Jeremiad-pitcher (the world is going to end, with a whimper) and the other a dispenser of smiles (the world is a buttonhole and I have a fresh daisy). I thought I gave them a credible basis for their dialogue, but I have to look at it fresh.

I loved West Wing—have to take a look at Newsroom. Thanks.

Actually, sounding too witty can be a problem. Sorkin’s characters pack the wit in tight, but most of his work only lasts for an hour or two. Keeping the wit at a high pitch for much of a novel can be draining. Also, unless you’re writing about the Algonquin Round Table or the Bloomsbury Group, giving all your characters rapier wit can keep them from developing as individuals.

The trick is to eliminate dialogue that shows no character. What’s left will show your characters more clearly, even when those characters aren’t masters of repartee and badinage.

Another good example is Stargate SG-1. Notice that the four main characters have different way of addressing each other. The soldiers refer to other superior officers by their rank, lower ranking officers by their last name and civilians by their first name. Teal’c refers to everyone by their full rank or title and name. Daniel refers to most people by their first name. It says a lot about the characters’ relationships.

I’ve never seen Stargate, though I’ve heard rumors about it. I’ll have to keep an eye out.

Whenever I read one of your posts I leave with homework, but unlike high school, it’s homework I want to do. I’m going to have to revisit The West Wing, start watching Newsroom, and check out the Wikiquotes page.

Also, I’ve never understood writers who knock TV. I’ve been told that I write emotion and dialogue pretty well, and I believe it comes from studying the shows I love. I watch them over and over to try to pinpoint the moments that moved me the most, and then figure out how and why. Why do I love that character and hate the other? Why does that scene punch me in the gut? Why do I remember that line of dialogue I heard eight years ago, but forget to take my daily dose of ginko biloba? Off to do some homework. :-)

I think that the knock against TV is much less convincing than it used to be. Television seems to be in a golden age at the moment, full of memorable dramas that are taking advantage of the long-form storytelling structure that a series offers. I haven’t mentioned the Gilmore Girls, which is a beautiful example of fast-paced, almost frenetic dialogue. Mad Men had some beautifully-balanced anti-heroes. Vikings does a brilliant job recreating the mindset of more than a millennium ago. Even Person of Interest, a personal favorite, manages the release of information in a way that’s astonishing. The show has gone on for four seasons, and we still don’t know the main characters’ real names.

These are just personal favorites, of course. I’ve also heard good things about House of Cards, The Sopranos, and Breaking Bad.

A curiosity? A couple years ago, we indulged in some nostalgia and watched the Donna Reed show. Ruth noticed that some of the shows were markedly better than others, with more original plots and stronger dialogue. Those shows were written by John Whedon, Joss’s grandfather. Unsurprisingly, John also wrote for The Dick van Dyke show, one of the bright spots of sixties television.

Good stuff! We are watching The West Wing series for the third time now for the same reasons. The character and fresh wit that shines through in the show’s dialogue is addictive. Thanks for the great parallel to reference in deciphering my own writing – strip away the mundane to find the voice of my character and carry it through like a knight’s javelin raised high to THE END!

Wow! Excellent post and comments. Will definitely try your exercise of isolating a character’s dialogue. Thanks for the link to the Wikiquotes page; I’ll save that for later.

I’m so glad you mentioned the epic monologue, too. I’d forgotten about this tool and how effective it can be (if not overused).

Although I’m a long-time Sorkin fan (and Whedon–hey, thanks for that fascinating bit of trivia!), I don’t have cable. Maybe someday I’ll have a chance to see The Newsroom.

We’re thinking of buying the complete set of Newsroom DVD’s, once they come out. It’s worth it.

Oh my word. I think I’m going to watch The West Wing with a notebook in hand now, Dave. Thank you so very much for this piece. I fight really hard for dialog. Everything else comes easy to me, but dialog for me comes about as easy as gold mining in a coal mine.

I’ll try these suggestions out. Thanks so much for the help.

Great dialogue examples, Dave. This post is really, really helpful–thanks! I’m going to the Wikiquotes page now…

Oh, thank you, Dave! This is a perfect post for where I am in my WIP. I also love the dialogue in The Wire and Downton Abbey. The latter is my favorite example of great subtext and great social restraint.

Grateful for this one!

I hadn’t thought about the way Downton Abbey captured the social restraints of Edwardian England. Another very nice example.

Sometimes I listen to the best TV series as if they were radio. I can absorb more dialogue when I don’t actually watch the action (I’ve already seen them dozens of times as well). It’s a great way to relax the eyes after writing for endless hours yet still be actively studying the craft of writing from the best writers. It’s a win win.

The soundtrack music also cues the ears for the necessity for increasing or decreasing tension and emotion. It’s good to be reminded that a story on the page also requires the balance of action without dialogue. Even when the actors are silent, the pacing of the story-line is reinforced in the spaces between dialogue – all elements that parallel a compelling written story.

All in all, great TV shows make for great radio. ‘Reading’ a story with the ears is a great screen saver for the eyes.

Very nice suggestion, thank you.

Love this article, thank you. I’m already a student of Dave King; I will now be a student of Aaron Sorkin as well.

So very excellent, this article. Will re-read and watch to see if I can implement some Sorkinese in my characters’ dialogues. The concept of dense in few words will not be forgotten.

Many thanks.