Ouch, My Feelings!

By John Vorhaus | January 23, 2016 |

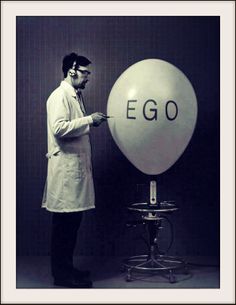

As the international television consultant I sometimes am, I sometimes find myself working with people coming into TV script writing from other forms of writing, for the simple reason that in many parts of the world (well, my world) trained and experienced TV writers are thin on the ground. For those coming into TV writing from backgrounds in solo writing, it can be difficult to adjust to the collaborative creative process that writing for television demands. Such writers often have the expectation that their feelings will be taken into consideration – that they’ll be treated gently. They quickly learn that in the hothouse environment of a TV writers’ room, your ego is your own affair, and any time you go, “Ouch, my feelings,” that’s pretty much a problem you get to have all alone.

As the international television consultant I sometimes am, I sometimes find myself working with people coming into TV script writing from other forms of writing, for the simple reason that in many parts of the world (well, my world) trained and experienced TV writers are thin on the ground. For those coming into TV writing from backgrounds in solo writing, it can be difficult to adjust to the collaborative creative process that writing for television demands. Such writers often have the expectation that their feelings will be taken into consideration – that they’ll be treated gently. They quickly learn that in the hothouse environment of a TV writers’ room, your ego is your own affair, and any time you go, “Ouch, my feelings,” that’s pretty much a problem you get to have all alone.

When I’m the bearer of this bad news, I try to break it gently – but, weirdly, not too gently. I don’t want to hurt anyone’s feelings, sure, but in the writers’ rooms I run, I don’t really want people’s feelings to be an issue at all. I want to get into productive collaboration as quickly as possible. So I ask my writers to join me in adopting a certain useful fiction (a useful fiction is something that everyone knows to be untrue, but agrees to anyway, for the sake of a common good). The useful fiction I’m promoting here is, “Inside this room, feelings don’t matter.” We all know it’s not true. We all know that our egos will make their presence known. But if we collectively commit to serving the work and not the ego, then we can go about the business of giving one another hard notes – often terribly brutal notes – without anyone wanting to open the nearest window and hurl themselves out.

Let’s say I’m giving story notes to a writer who’s never had anyone comment meaningfully on her work before. This is a very common situation in my line of work, and you would think I’d handle that writer with kid gloves. Yet kid gloves are the last thing I want. If I try to couch my notes in protective language, my message might not get through. Worse, my efforts to do so just reinforce the idea that protecting each other’s feelings is, or should be, our priority, which leads to more pulled punches and more lost efficiency. So I just say, “The notes are the notes. I know you’ll have an emotional reaction to them, but remember that here in this room we pretend that those feelings don’t matter. This clears out the space between us and lets us focus, together, on closing the gap between where the work is and where it needs to be.”

At the same time, I’m careful to focus my own notes on tangible observations, not value judgments. You’ll never hear me say that one piece of writing is “good” or another “bad.” Such subjective evaluations don’t interest me. I’m only interested in asking and answering concrete questions. “What is the intent of this scene? Has it been achieved? If not, what changes can we make to correct that?” So now I’ve taken feelings off the table, but I’ve also removed attacks on feelings. Now everyone’s ego can relax, and we can start to work effectively as a team.

Does it sound like I’m trying to have it both ways? I am, and I do. Even while I’m teaching my team to filter their efforts through service to the work and not service to the ego, I’m also shaping a culture that protects ego and lets egos let down their guard. What I’m after, ultimately, is a free floating generosity of spirit where everyone can contribute their ideas because they know their egos won’t get stomped on, but can also accept others’ input because they know their egos aren’t at stake. I often reduce all of this vexing interpersonal complexity to a trivial one-liner: “Let’s save our egos for the award ceremony.”

I love running writers’ rooms. I especially love running them with this open, honest approach, at once analytical and empathetic, that helps writers achieve the transition from isolated and scared to integrated and groovy and cool. Television writers’ rooms can be soul-killing places. They don’t have to be, but often they are, simply because people focus on their ego issues the wrong way. They think ego is a war that needs to be fought and won. My rooms aren’t run that way. My rooms are fun. I wish we could all be in one big one together right now. I know we’d have a real good time.

And why do I bring this up out here? Because even for solo writers, writing professionally is an intensely collaborative process. We collaborate with our writing groups, agents, editors, publishers, publicists, illustrators, mentors, friends and fans, and every time we filter information through ego, we risk losing information that could be doing the vital job of improving our work. So see if you can take “ouch, my feelings” off the table for yourself. Instead of asking of input (from a beta tester, or reviewer or whomever), “How does this information make me feel?” try asking, “How can I use this information to close the gap between where the work is and where I want it to be?” If you do this, you will be genuinely in service to the work, and then a marvelous alchemy takes place: The work will improve. Well, why wouldn’t it? You got useful input and put that input to use. Now you have a better product, and how does that make you feel about yourself? Better, of course. So instead of, “Ouch, my feelings,” it’s “Yay, my feelings!” It’s almost a Zen reduction: to serve the ego, ignore the ego. The ignored ego feels less stress, therefore performs better, produces more, and ends up being profoundly served.

Have you ever found yourself in a bad spot with another writer where they say they want the cold, hard facts, but really only want your approval? What do you do about that? Meanwhile, what strategies do you use to keep your own demons of ego at bay?

[coffee]

John, this is going up on my online crit group’s G+ page.

Everything you say is what we strive to do for each other. Yes, we all write long form fiction, but still, this is the process and it does work.

Love this post. As an official registered card-carrying Cranky Old Lady (maybe I should say Disturbed Chronologically-Challenged Female, but that sounds worse), I’m from a less-sensitive era, and I am just bumfuzzled about the current wave of sensitivity issues, not just in writing groups, but everywhere. Working as you do in sort of an emotional-neutral atmosphere, with the primary focus on the project, is the best way to a super end-product, with no hurt feelings and/ or pointed fingers.

….Have you ever considered running for President?!?

Couldn’t pass the drug test.

John, my knowledge of TV writers’ rooms comes from watching 30 Rock and the x-tras on The Good Wife. The GW room was full of energy, people tossing ideas, embracing, rejecting others. People were smiling. I wanted to be there!! I was part of a long-running critique group that actually had moments like this, depending on who was present. But we had folks who refused to hear anything other than praise, and what I saw over the months (and years) was stagnation. My ego got plenty bashed around in that group, but I finally realized that if I was really serious about writing, I needed to find a way to ignore the hurt feelings. I also learned that good notes make the work better, and that the work was all that mattered. “…in service to the work” says it all for me. And yeah, my ego still gets bruised, but it recovers. I love this post. Thanks!

John–thanks for this application of writers’ room etiquette (yours, anyway) to those who work in their own little room. But you also need to include advice on how to evaluate the evaluator.

As you say, ego is an impediment to gaining full value from a critique or reaction to one’s writing. But ego is no less in play for the one giving the critique. You say you are “careful to focus my own notes on tangible observations, not value judgments.” Probably, this is true for you, but of course I would have to see you in action and read you notes to be sure.

What I do know is that readers who make judgments about someone else’s writing can be smart, dumb, generous as well as straightforward, or defensive. They can be nonstop cheerleaders for work that supports their own biases, or blind to work that doesn’t.

In other words, while the writer must be open to hearing and learning from criticism, s/he must simultaneously be a good judge of those who offer up criticism. And a fancy list of publishing or other professional credentials is by no means a guarantee that the critic/showrunner in the room is “objective.”

That’s absolutely true, Barry. Some of the worst editors I encounter are the ones who can’t see past their own “improvements.” A friend of mine expressed it this way once, speaking of movie producers: “When a producer tells you what’s wrong with your script, s/he’s almost always right. When s/he tells you how to fix it, s/he’s almost always wrong.”

Great post!

As someone who’s highly sensitive, it’s taken a lot of effort for me to get to the place where I receive critique about my writing as just that: critique about my writing. My knee-jerk reaction is always to take it personally, but I’m learning to push past those “feelings” and get to the real reason I look for critique – to improve my writing. Thanks for this. I’ll be sharing with my critique group.

Hey, John:

I have a note on my computer: Remember — creativity is a contact sport.

Your advice is also excellent for working with editors — especially editors who may not find fault with your piece as much as find it less than a perfect for what they’re trying to accomplish with their magazine, anthology, imprint, etc.

Recently I’ve had two exchanges with editors who, though pleased with my work, wanted changes based on what they were hoping for in the larger context of the anthology they were assembling, or to serve the needs of the expected audience of the larger work.

I am not proud to say my initial reaction was resistance. Not from ego so much as, well, laziness. “If you admit the piece as fine as is, why insist on changes?”

Now, ego was definitely involved. I was hearing, “The piece is fine,” not “It can be better.”

These requests for changes came after two of those glorious submissions where the editors gushed and said I’d not only met expectations but wildly exceeded them, with a WD piece earning me several fan letters, etc.. So I thought I was on a roll.

Um, I wasn’t.

In the end, I did the requested rewrites, and of course the changes made me think more deeply and clearly not only about the parts that needed changing but everything else — because in any strong piece of writing the part serves the whole and changes to one create a ripple effect in the other.

Are the pieces better? Yes, for the simple reason they forced me to take one more hard look. And they certainly better serve the editor’s vision in both cases — and that’s enough to justify the additional reworking of each piece.

Another quote I keep in mind (if not stuck to my computer): We don’t know ourselves by ourselves. Which is just another way to say: We do not work in isolation. And that keeps us honest.

Good luck massaging those prickly egos. Or sandpapering them down. Whichever analogy applies in the given moment.

Through countless drafts of a certain script, the director kept telling me, “This is great! Now I know what I don’t want!” It was an odd way of pushing me past my ego, but it worked. He clarified that just because the work is working, that doesn’t mean it can’t be working better. And yes, sometimes it’s hard to tell where laziness leaves off and ego begins. Self-awareness; self-acceptance. In writing, as in everything, that’s the name of the game.

One thing I think is worth mentioning… While it is a good idea to “take off the kids’ gloves” when critiquing, positive feedback is just as important as negative.

And I’m not saying that out of concern for anyone’s feelings, but they need to know what works as well as what doesn’t work. Especially newer writers, who are still learning the craft.

Agreed. When I’m marking up a script, I make liberal use of the acronym MLTP (More Like This Please). I point out what’s working and why it’s working so that that part of the process can be repeated more easily. But, as you point out, that’s not “praise for the sake of praise” but feedback that’s tangible, concrete and a contributor to good process and good product.

JV,

Great thoughts, as usual. As for me, I have a helluvan ego. I know this. I’ve craved the spotlight ever since I can remember. That being said, I certainly don’t want crappy work spotlighted…or would that be spotlit? Somebody help me out here. Where’s a good CP when I need one?

Anyway, I’m in no way under the delusion that everything I write is perfect. Well, not every time, that is. And I can take it. My skin thickened decades ago. I look at the facts as given, even when they’re delivered in emotional wrapping, and work from there.

It took me awhile to find a group of trusted, knowledgeable friends with whom I could get honest-to-goodness feedback. I mean, seriously, they tell me exactly how it is with no sugar coating. I appreciate them more than a thousand yes men. That which doesn’t kill us makes us stronger, yes? (Okay, this is where I give you permission to be a yes man).

Thanks for your continuing sagaciousness. See you at the SAG Awards. ;)

“If I try to couch my notes in protective language, my message might not get through.”

MLTP.

I see a lot of people recommending the “compliment sandwich”, where the criticism is sandwiched between compliments. The problem with this is people focus on the compliments and ignore the message.

I like your take on it: that it’s the responsibility of the person receiving feedback to forget their feelings and focus on improvement. Yes, critiquers shouldn’t be deliberately nasty, but nor should they have to walk on eggshells for fear of offending a sensitive snowflake.

“If I try to couch my notes in protective language, my message might not get through.”

Thanks for bringing this up. One of the biggest adjustments I had to make when I first moved to Australia was to learn that the polite comments I received were sometimes actually criticisms. In America, where I came from, you had no doubt what the straightforward responses meant! My first introduction to this was in a meeting with our boss who was talking gently to a colleague about a botched incident. Later a workmate said to me, “boy, he really told her off, didn’t he?!” DID HE? That’s not how I had heard it!

John, I love your attitude. Seems to me you’ve established safety, are modeling the attitude you seek to create, and by the tone and parameters, are declaring that you expect people will rise to your high standards. That’s the kind of setting I find the most exciting and fulfilling, if challenging.

I’ve been in bad rooms. I was brutalized by the egos in bad rooms, and made myself a vow that when it was MY room, things would be done much differently. I think it’s my own keen interest in the “process” that helps lubricate the interpersonal dynamic of my writers’ rooms. I’ve always been about “isn’t that interesting?” rather than “is that good or is that bad?” An observational eye keeps ego investment at bay.

I got goosebumps reading this. It’s my dream to work in such an atmosphere where such creative impetus can be created and ego, for the most part, banished.

At the end of the day, all I want to do is create good, solid work. My ego can handle a few bumps and bruises as a means to an end. I want information that’ll “close the gap between where the work is and where I want it to be.”

Thank you for this!

I love this no bullshit approach. It works on so many levels.

I love this! The real trick, it seems to me, is that you’ve actually created a safe zone where it’s not about feelings, which makes feelings less likely to rear their heads in ugly ways to begin with. “At the same time, I’m careful to focus my own notes on tangible observations, not value judgments.” I know many a critique partner who could benefit from this, and thus many a critique receiver, too. If we all focused on non-emotional feedback, it would be more helpful AND easier to receive. If only the writing community at large was as healthy as your writers’ room!

It’s worth noting that the whole proposition rests on the useful fiction that “we’re all serving the work, not our egos.” In (some of our) hearts, we know that’s not true, but for the common good, we buy in to the consensus idea — the useful fiction — that it is. This demonstrates one of my favorite ideas, that “a useful fiction may be fiction, but it’s useful just the same.” I’m very frank about telling my writers what the useful fiction is, why it might be a lie, and how it can benefit us all just the same. This is congruent to the Buddhist idea of “right action, right mind.” By encouraging writers to follow the path of “right action,” I bring them around (pretty quickly usually) to “right mind.”

Great post. Tweeted it. Too many people assume writers are like spys, as described by Bruce Campbell in Burn Notice: “bunch of bitchy little girls.” Not true. How can we get better without honest feedback? The truth may hurt, but–sorry to be a cliche–it can also set you free to try harder.