Obtaining Reversions of Publishing Rights: the Good, the Bad, & the Ugly

By Susan Spann | January 10, 2016 |

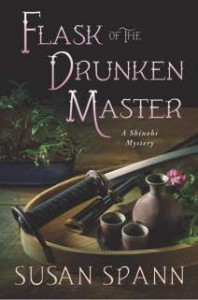

Please welcome guest Susan Spann, a publishing attorney and author of the Shinobi Mysteries, featuring ninja detective Hiro Hattori and Portuguese Jesuit Father Mateo. Her debut novel, Claws Of The Cat (Minotaur, 2013), was Library Journal’s Mystery Debut of the Month and a Silver Falchion finalist for Best First Novel. Her third Shinobi Mystery, Flask Of The Drunken Master, released in July 2015, and the fourth is scheduled for publication in August 2016. Susan is the Rocky Mountain Fiction Writers’ 2015 Writer of the Year, and the founder and curator of the Twitter #PubLaw hashtag, where she provides publishing legal and business information for writers. When not writing or practicing law, she raises seahorses and rare corals in her marine aquarium.

Please welcome guest Susan Spann, a publishing attorney and author of the Shinobi Mysteries, featuring ninja detective Hiro Hattori and Portuguese Jesuit Father Mateo. Her debut novel, Claws Of The Cat (Minotaur, 2013), was Library Journal’s Mystery Debut of the Month and a Silver Falchion finalist for Best First Novel. Her third Shinobi Mystery, Flask Of The Drunken Master, released in July 2015, and the fourth is scheduled for publication in August 2016. Susan is the Rocky Mountain Fiction Writers’ 2015 Writer of the Year, and the founder and curator of the Twitter #PubLaw hashtag, where she provides publishing legal and business information for writers. When not writing or practicing law, she raises seahorses and rare corals in her marine aquarium.

As an author and transactional attorney with almost twenty years’ experience representing authors, publishers, and artists, I understand how critical it is for authors to understand their legal rights—and how few good sources of legal information exist for authors seeking to learn how to do it. I founded the #PubLaw hashtag, and wanted to blog for WU on legal issues, to help empower authors by providing information about writers’ legal rights and how to protect them.

Connect with Susan on her blog, on Facebook, and on Twitter.

Obtaining Reversions of Publishing Rights: the Good, the Bad, & the Ugly

In my work as a publishing lawyer, I frequently hear from authors hoping to terminate publishing contracts and obtain a reversion of rights to their published works. Rights reversion can be tricky, especially when the contract doesn’t give the author a unilateral (meaning “one-sided”) right to terminate. However, authors do have several options when it comes to terminating old or dysfunctional contracts and obtaining reversions of publishing rights.

Today, we’ll walk through the steps an author should follow to try and obtain reversion of publishing rights from a traditional publishing house.

Step 1: Review the Contract. In almost all cases, publishing contracts contain provisions stating when and how the contract can be terminated, and by whom. If the contract allows you to terminate under your current circumstances, follow the procedures in the contract to request reversion of your rights. Normally, these procedures include a written notice to the publisher (often sent via certified mail) stating the reasons for termination. Comply with the contract procedures exactly. If you have questions, or don’t understand the contract terms, consult a publishing lawyer.

Step 2: Ask the Publisher to Revert Your Rights. If the contract doesn’t grant the author the unilateral right to terminate, or if your situation doesn’t meet the requirements for unilateral termination, consider asking the publisher to agree to termination of the contract and a reversion of rights. By law, the parties to a contract can always modify or terminate the agreement by mutual consent, even if the contract doesn’t say so.  Many publishers will agree to terminate and revert the publishing rights to works when sales have dropped so low that keeping the work in print creates more obligations than benefits. Make sure your request is polite and professional—regardless of the nature of your relationship with (or opinion of) the publisher. Respectful communications receive more consideration than insults or threats.

Many publishers will agree to terminate and revert the publishing rights to works when sales have dropped so low that keeping the work in print creates more obligations than benefits. Make sure your request is polite and professional—regardless of the nature of your relationship with (or opinion of) the publisher. Respectful communications receive more consideration than insults or threats.

Step 3: Consult a Publishing Attorney. If the contract doesn’t grant you obvious termination rights and the publisher refuses a polite request for termination and reversion, there may still be creative ways to obtain termination of the contract and reversion of publishing rights.

However, in most cases the author’s right to terminate a contract and obtain a reversion of publishing rights is limited by the language in the agreement. If the contract doesn’t grant you termination rights, and publisher isn’t in breach, your options may well boil down to persuading the publisher to agree to termination—or waiting until the contract allows you to terminate without the publisher’s consent.

Which brings us to the final, forward-looking step in the process…

Step 4: Ensure all Future Contracts Contain Unilateral Termination Rights and Out of Print Clauses Tied to Royalty-Bearing Sales. This won’t help much with your old agreement, but will ensure you don’t end up in this situation again.

Going forward, make sure all agreements you sign contain:

(a) A unilateral right for the author to terminate the contract if the work goes “out of print” and

(b) Language tying “out of print” status to a stated number of royalty-bearing sales. (For example: “the Work will be considered “out of print” if the Publisher fails to sell at least 250 royalty-bearing copies of the Work during any period of twelve consecutive months (or longer) during the term of this agreement.”)

Note: Sometimes the publisher may want an additional 6-12 months to increase sales and return the work to “in print” status before your termination becomes effective. That’s fairly standard, too.

Tying out of print status to royalty-bearing sales and giving the author the unilateral right to terminate if the work goes out of print makes the contract more balanced in terms of ensuring that the publisher’s rights continue only so long as publication of the work is actually profitable. This language also prevents a publisher from claiming a work remains “in print” as long as the ebook is available through Amazon or the publisher’s own website.

Unfortunately, once the contract is signed, an author’s rights are limited to the contract terms (unless the publisher agrees to a request for termination). When it comes to publishing contracts, the best defense is a good offense—negotiating for unilateral termination rights in the agreement, before you sign.

Your turn: Have you terminated a contract and obtained rights to your published works? What was your experience?

Thanks very much Susan! I must say, this is possibly the most I’ll hear from a publishing attorney in my career, so it was especially valuable.

As one of the unwashed masses of indie authors, I’m quite sure that in the event I was offered a contract from a major publisher, I’d be a nervous wreck and hard pressed to find the courage to fight for my rights. If you would care to render some more free advice- one signs with, say, a mid-sized publishing house, and the attempt to insert termination language is initially rejected by them. Is it worth fighting for? Do you think most places would really stand on some of the “lifetime of the author plus 70 years” language we’ve been horrified to read about? Or is it a bluff?

Will, I’m glad to answer additional questions — both here and via my website or on Twitter. I think lack of information is a critical issue facing writers, especially as indie publishing expands, and I try as hard as I can to help keep writers informed about their legal rights.

It’s definitely worth pushing for the better termination language. Generally, you’ll see the “bad versions” of that language in contracts that have many other problems, too. Whether or not the publisher is willing to change the language to meet current industry standards is actually a good litmus test for whether you’ll have a good experience with the publisher. (It’s not 100% accurate, of course, but pretty close.) The key is knowing what to ask for, and how to ask for it.

However, you’re better off walking away from a contract than signing a bad one. Having no contract is actually MUCH better–for you and for your work–than having a bad one.

Thanks, Susan, and WU, for providing this kind of valuable information to authors!

I’m glad I could be here and share the information, Carmel!

Very nice overview, Susan. As a recovering lawyer, I’d like to toss you this hypothetical (just so you can relive how wonderful it was to take the Bar).

Book pubbed in 2000, still “in print” per contract. Author asks politely for rights back. Refused. Any further action is the burden of the Author, and starts running into actual money.

So Author, copyright holder, updates and revises said novel. Thus it becomes a “new work.” Then releases new version himself, perhaps with a new title. Publisher claims this violates non-compete, but author claims restraint of trade. Burden now falls on the publisher.

Who has the better case?

Great hypothetical. I taught law school for several years, and I have to admit, this isn’t far off the ones I’d give my students.

The short answer, of course, is probably the one you expect: it depends on the precise terms of the contract.

Many contracts contain non-competition language that’s far too broad (and I do mean FAR too broad) for fairness. That said, it’s in the publisher’s interest to prevent the author from re-releasing another (even edited) version of the same work.

The slightly longer, but still short, answer is that if the book is really the same work, and hasn’t been substantially transformed into a truly “new” work, then the publisher has the better case.

However, I’ve seen situations where a novelist took a novella-length (or short-story length) work and truly transformed it into a much longer (generally full length) book, and the transformation was probably substantial enough to pass this test.

Ultimately, though, it’s going to depend on the terms of the contract–which is one reason why I strongly advise writers to get good representation (an attorney, an agent, or both) before going into a contract negotiation–to ensure that they get the best-possible language for termination and rights reversion.

I’ll add, also, that the changing landscape of publishing makes it even more important for authors to consider carefully whether it’s worth entering into overly restrictive contracts at all. I’m hoping (as is the Author’s Guild) that publishers start offering more reasonable termination language–we’re seeing some movement, though not quite enough in some cases, as yet–but those of us in the trenches will keep trying.

You are so right about a good offense. Protective contract language right up front is the best way to get your rights back.

Already in comments here we see frequent questions. What if I don’t have an agent? Can I really negotiate with Evil House Publishers when I’m just poor little me? Answer: yes. The biggest lever you have in negotiations is the word “no”.

Does revising so that it becomes a “new” work get you out of your contract? Does a complaint of restraint of trade trump a breach of the contract non-compete clause? Susan’s in a better position to answer but from a practical point of view I’d say you’d be risking more legal expense than this dodgy strategy is worth.

Susan, perhaps you mention the ultimate fallback in copyright law, the termination of copyright licenses thirty-five years later? It’s drastic, delayed and technically difficult but it does exist. (Do get an attorney experienced in copyright law.)

Thanks for this post. Reversion is one of the issues in contracts that comes up most in the real world. As an agent I spend almost as much time on this per title as I do getting the contracts in the first place. Well, feels that way. Thanks for your solid advice.

Thank you, Don! (Incidentally, your WRITING THE BREAKOUT NOVEL was instrumental in getting me over the final hurdles to publication of my fiction–so thank you for writing that fantastic book.)

Don’s answers are on target here–experienced agents and publishing attorneys see a lot of the same things in the trenches day-to-day, so from a contract perspective a lot of us are on the same page.

You absolutely can–and should–and I think *must*–attempt to negotiate contracts, and do not be afraid to walk away if the publisher is acting dodgy or refuses to give you fair, industry-standard terms. I have seen publishers change their strategies, and their contracts, both for a single author and in response to authors’ unified refusal to accept unfair terms.

I also agree that the strategy in the hypothetical is dangerous, and probably not worth doing. Certainly not worth doing without a copyright litigator’s advance written opinion.

Don also mentions the 35-year reversion under copyright law, which is a technical (and tricky) situation involving reversions of rights to works under contract pursuant to 17 U.S.C. Section 203 (a section of the Copyright Act). It’s a long-term strategy, and definitely involves attorneys. The short-form memo to authors is: if your work has been under contract for over 30 years, talk to a copyright lawyer to see whether this might help you when you hit that 35 year mark. (Also, I recommend consulting a lawyer any time after the 30-year mark, even though that’s early, to ensure you’re ready to act as soon as possible when the time comes.)

Great information for authors. My first children’s book went out of print with a major publisher, but the illustrator and I loved it. So we did as was laid out in the contract and obtained the rights back. A bit later…..the publisher got in touch with me to ask if I’d review some text for the paperback version of the book they were preparing to release. OOPS! They had not even checked to see if they still owned the rights. The publisher had to buy the rights back from us to publish the paperback version, which is still in print more than ten years!!! No lawyers or agents were involved.

Great work, Ellen–and congratulations on the success of the book, as well.

I do advise authors to get the assistance of agents or attorneys before signing or negotiating contracts with major houses, primarily because those houses have representation and it’s easy for authors to miss or overlook important terms. However, it’s always lovely to hear about a situation where things worked out well–and I’m delighted to hear that you were able to get the work in print in the way that worked best for you and the illustrator. Ultimately, that’s what all of this is about!

My mystery/suspense novels were published twenty-five years ago, and my contracts required me to give notice of my desire to have my rights revert. The publisher (a major house, with my original publisher subsumed under the larger one) had ninety days to decide to re-issue the books. Obviously they weren’t interested in doing so. The hardest part was figuring out where to send my certified letter. The web site of the major house did not offer any “business address” for people like me. Although I was able to find a NY address, I did worry about sending my request to the general address, thinking that it might fall through the cracks if not provided to the correct office. I found a link to a “permissions” department and emailed, requesting an address and office for rights issues. Fortunately, someone in the permissions office came to my aid and redirected my queries. I finally obtained written notice of the reversions.

I guess the moral here is that the correct office for such queries might not be easy to find. If your book has recently been published, you are more likely to have an address for the business side. In my case, a great deal had changed, and my old contacts had long moved on.

Thanks for providing such important information!

Your comment gives a great blueprint for authors in your situation–the best way to find the address you need, if it’s not in your contract and years have elapsed since signing is to do exactly what you did–email the permissions department and ask where to address your inquiry or letter.

It’s actually what I do when I have to find out the status of copyrights and contracts on works for estate clients tracking down the rights to works published many years ago, after the death of the author.

Good work!

Hi Susan, I really appreciated your article about obtains reversion of a published book. My question is when you give notice and you’re released from a contract can you still use the. Same book cover upon using Createspace or another outlet to put your book out there again?

I’m not a lawyer, but I would say no. The reversion of rights applies to the contents of the book the author wrote, not to the art the publisher designed for it, because the author didn’t own the rights to that art to begin with. Besides, if sales were low enough for the publisher to willingly revert the rights, or to be legally obligated to revert them because the work fits the definition of “out of print,” a re-branding is probably in order anyway. It would be in the author’s best interest all around to hire a designer to create an updated cover.

Marlene, the answer depends on whether you owned the cover art. In most cases, the publisher designs the cover (or hires an artist) and therefore owns the cover art. In some cases (particularly with small publishers), the author provides the cover art (and, presumably owns it–though sometimes the contract actually gives the publisher rights to that art–a tricky clause a lawyer or agent would spot, but that authors often miss).

Whoever owns the art has the rights to control its use.

If the publisher owns the art (the normal situation) then you cannot use it. At least, not without obtaining a license and written permission from the publisher. (Get the writing in “real” writing–a license, not just an email.)

If you own the art, you can use it, provided the contract didn’t transfer ownership to the publisher.

Ultimately, the answer is: check the contract.

Susan, thank you for useful information, courtesy of a professional. I have a question: I imagine more and more commercial publishers will be using Print On Demand for some if not all of their list. If so, how will it be possible to apply an out-of-print clause for such books?

Hello Barry,

The rise of POD (Print on Demand) technology and its use by publishers is one major reason for having contract language that ties the author’s termination rights to sales (and, preferably, “royalty bearing sales”). If you have the right to terminate when sales fall below a stated threshold (X copies in 12 months), then it doesn’t matter whether the book is POD or not–what matters is how many copies it sells.

As a realistic matter, POD books tend to sell fewer copies than books which are more available to bookstores (partially due to exposure and partially due to the higher price for POD) so as long as the contract contains a sales-based termination provision, the author will have some recourse if the book goes to POD status and doesn’t sell or stops selling.

Hope that helps!

I have managed to get one of my books returned from a major UK publisher, but they were so grudging about it. Your idea of creating a ‘new’ work’ is exactly what I am about right now with another book. So sue me!

I’m sorry to hear your publisher was grudging about the return of rights; unfortunately, far too many of them are. However, I’m glad to hear you’re working on your next project, and I hope it’s a great success!

Another recovering lawyer here – but they do say that a lawyer who acts for him/herself has a fool for a client.

I have requested termination of contracts with two publishers. The first contract allowed for mutual termination so was relatively painless. The second did not have that handy clause. However the books had not been selling so after a little harrumphing and chest beating the publisher let me go. I did not own the artwork (who wanted it anyway!) and the publisher also claimed rights to the edit and the blurb. Easy fix – I just got the books ‘re-edited’ and redid the blurbs. Small price to pay for getting my rights back.

Contracts which terrify me are those which have terms purporting to be for the life of copyright and some. Somewhere in the depths of my legal training the words ‘unconscionable contract’ comes to mind. I have walked away from a publisher offering that term and who wouldn’t negotiate a fixed term of a number of years and I would advise any author to do the same, particularly if the contract also includes an option for new work using the same characters. You are shackled for life and beyond the grave!

One thing a lot of people don’t realize about “life of copyright” contracts–almost all publishing contracts contain the language “life of copyright” in them somewhere–but that doesn’t actually mean you’re shackled forever.

The key is understanding that the contract is only for the life of copyright IF it isn’t terminated earlier than that, pursuant to one or more of the contract terms (or by mutual agreement of the parties, or by a court). That’s why it’s so important to get good termination and rights reversion language in the contract. The contract’s “life of copyright” provision doesn’t matter if you have the right to terminate when sales fall too low, if the publisher breaches, or at other important points.

I was published by a small press, for the first time, in 2010. I was so green. Thankfully the publishing house I worked with was pro authors. The entire experience was very positive from start to finish. When I realized that I could write romance but that I wasn’t a romance author, I emailed my publisher and she walked me through the revision of publishing rights.

This is exactly the kind of story I like to hear. Professional publishing houses that actually care about the authors are often willing to work with authors when the time comes to part ways. It’s always nice to hear about the times when things went properly, both at the start and at the end of the relationship.

That’s pretty interesting. Any small press contracts I’ve signed (both for short stories and novels) either have full rights return after a certain time period, or have automatic renewal after that time period if neither party objects. I never knew the contracts were so different between traditional and small press.

Thanks for the great information.