Getting the Most out of Mentoring, from Both Sides of the Fence

By Sophie Masson | November 9, 2015 |

Nobody writes in isolation. Writers experience mentoring in one way or the other at every stage in their careers. Early writing mentors are usually teachers, family and friends. Later, as we take our first steps towards trying to build a career as a writer, other, more professional mentors can improve our understanding of craft, as well as give us the confidence to take those first tentative steps.

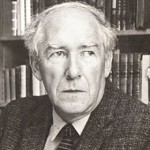

As a young writer who initially saw her potential in poems and short fiction, I first experienced the power of mentor-ship after sending my work to famous Australian poets I’d studied at school. This naive bit of boldness resulted in some memorable responses—all of them generous and kind towards the young writer who had written to distinguished authors out of the blue. Several were helpful in both practical and creative ways. One of them, the eminent poet and literary academic A.D. Hope (pictured) even wrote to me two or three times, giving me extensive advice on several new poems, as well as the addresses of magazines I might send them to. Thus it was that I learned not only ways in which I might improve my craft and where I might send work for publication, but also two other important lessons: how generous and supportive other writers can be, and how important it is to be mentored by authors more skilled and experienced than you are.

That was my first experience of mentoring by writers, but it was not to be the last. By the time my first book was published and I had moved from the informal experience to the more formal framework of ‘mentor-ship’, otherwise known as working with editors in a publishing house, my craft had been improved as well as confidence in my own voice.

Throughout my publishing career, and, like, I’m sure, many other writers, there have been times when I have been part of an informal quid pro quo mentor-ship with writer friends as we read each other’s manuscripts and make suggestions and comments–this is especially useful if you are moving into an unfamiliar genre or trying to work out why something isn’t working for a publisher. Remembering my own experiences, I’ve often informally mentored young and emerging writers, and formally through schools programs. I have also been involved in formal arrangements with adult authors where I have been a paid mentor to new and emerging writers through official mentor-ship programs run by such bodies as the Australian Society of Authors and the various writers’ centres and organisations in this country. (I am sure there are many such similar programs in the USA and other countries).

Through all these experiences, both of being a mentor and a mentee, I’ve learned not only that trust is the essential ingredient on both sides, but also gained a wider understanding of the elements that make a successful mentor-ship experience, and what elements can make it fail. Here’s some of them, from both sides of the fence. They are especially applicable to formal, paid mentor-ships, but are also relevant to more informal arrangements.

A good mentor:

*Reads the work, or portion of your work under examination, carefully.

*Looks at your work objectively, on its own terms, and does not try to turn it into something they’d write.

*Couches advice in clear but not blunt terms.

*Makes useful and constructive suggestions about important things like structure, language and characterization, not spend their time correcting you on spelling or grammar (unless of course that interferes completely with the important things and the potential for publication).

*Does not try to force suggestions on you.

*Makes suggestions as to how to proceed next, in terms of the creative development of the manuscript.

*May provide practical tips for sending a work to publishers, if of course the work is deemed to be at that stage. (This is a ‘may’ as I don’t believe mentors should feel obliged to pass on publication contacts etc—this is up to the mentor’s discretion).

A good mentee:

*Listens to the advice of the mentor.

*Is flexible enough to consider looking at their work in a new light, but confident enough to be able to express politely why they might not agree on any aspect of the advice.

*Keeps within the mentor-ship agreement, such as not bringing in extra pieces of writing when the agreement is focused on just one project.

*Does not expect the mentor to be a cheer-leader for their work.

*Does not expect a mentor to do a line by line or even chapter-by-chapter manuscript assessment (which is a very different process).

*Does not get into a huff about constructive criticism, civilly expressed.

*Does not expect the mentor to give them an introduction to their agent, or their publisher.

Over to you: what have been your experiences of mentor-ship? And what do you think makes for the best kind of experience, from both sides of the fence?

Important topic, Sophie, thanks for putting it in the spotlight. Looking at your checklist for mentors makes me realize how incredibly lucky I am. I’m grateful for my awesome mentors.

As far as mentoring others, I might mention that the role can be important to young writers outside of the actual critique of the work. I recently had lunch with an aspiring young writer, and while he didn’t feel quite ready to share his work with me, I think he was reassured to hear he was on the right path, doing the right things (he really is!). And to know that it’s an ongoing journey, that we all fight the same fights, and must overcome the same doubts. I have a feeling this kid’s going to be great, and that’s exciting. Spending time with him was a heartening reminder of what a special calling this is, perhaps as beneficial to me as to him.

Thanks again for the post, and for all you do for other writers, Sophie!

Thank you, Vaughn, for those kind words! And you are so right–that supportive contact with other writers at a different stage of experience can be just as beneficial to onself as to the other person.

Thanks for showing both sides of the fence.

Great advice, Sophie. Practical and clear and should be read by anyone entering into this type of a relationship for the first time. Bottom line: 1) there is an etiquette and 2) check your egos at the door!

Absolutely, Deborah!

Excellent advice! I’m always so impressed by the supportive writing community, both online and (in my case, at least) locally. As I’ve advanced in my writing career, I’ve had the privilege of working closely with newer authors. Not all editors are willing to take on these authors, because it does require a different kind of mentoring than more experienced writers, but I really enjoy having a certain number of new writers on my roster.

I also appreciate your comment about writers needing mentorship at every stage of their career. That’s so true! One of the many wonderful things about being a writer is we can always improve and strive to push ourselves. It really does make writing so fun.

Thanks for the insightful post.

And thank you for your insightful comments, Donna.

Lovely post. I think in any profession, even after developing some competence, we are pushing ourselves to be better. But in the arts, it seems we’ll always have that quality of being an apprentice. Maybe this is why I enjoy teaching so much.

This is wonderful stuff, Ms. Sophie.

I have never had a writing mentor, but I’ve had mentors in film production and songwriting and entrepreneurship among many other disciplines and the best ones have all the same sort of things you listed.

I would, however, make an addendum:

Sometimes you need blunt rebuke. Sometimes I would not have changed unless an older, wiser, better (as in “a better man than I”) man hadn’t taken me out to the woodshed and whipped me into shape. I can think of four or five very strong rebukes that saved me from myself at different points along the way.

And I would hope a writing mentor would do the same to me. In fact, I received a recent critique from someone I respect and the bluntness that cut to the heart of the novel’s problems was quite possibly the most refreshing moment of my career so far.

But, again, it’s possible that others are too tender for this and may apply only to me personally, one way or another. If it would break a bruised reed, I doubt that the writer in question is ready — emotionally — for such a rebuke. It does, however, strengthen me every time.