Bombing Through It

By Dave King | May 19, 2015 |

Back in the nineties, before social networking or even blogs had been invented, I belonged to a chat list for published writers. You carried on a slow conversation with like-minded people by sending e-mails to a central server, which then sent them out to all members of the list. Tom Clancy, another list member, used to give a piece of advice to writers who were stuck at various stages of the writing process: “Just write the damned book.”

I think of that advice whenever potential clients ask me to read over the first few chapters of their work in progress, to make sure they’re “on the right track.” They don’t seem to realize that there is no track. When you write your first draft, you lay the tracks as you go. As you follow your story, you may find out that a minor character moves to the center of the action, or that a plot twist you’ve been building toward for a hundred pages just won’t work. Or your story may simply transform into something else as you write it. In its original draft, William Golding’s Lord of the Flies was magical realism, with Simon having genuine mystical visions and sacrificing himself willingly at the end.

The process is a little different if you work from a detailed outline, but not much. True, you do have an idea of where you’re going when you actually begin writing. But some of the creativity and surprise – the getting to know the story and characters – that other writers experience with the first draft, you get with the outline. And no matter how detailed your outline might be, you should still treat it more as a guide than a rulebook. The actual process of getting the story down on paper has a unique intimacy and particularity. Stories are organic. You’ve got to let them grow as you write, even if you’ve already built a trellis.

Still, the problem those clients are looking to me to solve is real — a lot of writers get lost in the middle of their first draft. One reason may be a lack of confidence and drive. I find it’s usually second novels that I’m asked to keep on track. Many writers enter the field because they’re burning to tell a particular story. But after the first novel is done and they launch into the second one, they often lack the passion for the story that got them through the first novel. After The Joy Luck Club, Amy Tan began and abandoned seven different second novels — at one point breaking out in hives — before writing The Kitchen God’s Wife.

You can also trip up on your first draft by focusing on the mechanics of writing – like the beginning writer who recently complained on the Writer Unboxed Facebook site that, whenever she read a how-to-write book, she felt like she was going about it wrong. It’s easy to get so obsessed with the technical details – how you’re managing your micro-tension, if you’re giving your readers enough physical description to imagine the scene, whether your antagonist is sufficiently balanced or your dialogue is pithy enough – that you can’t find your story. You’re like the centipede who was asked which leg she lifted first when she walked – and never walked again.

On the other hand, not having a firm enough grasp of the basic skills of storytelling can also run a first draft into the ground. If your descriptions are inept, then your locations will never take on reality. Flaws in your management of point of view can keep your characters from coming to life. So what you’re writing may feel flabby, impotent, just plain wrong, which makes it hard to keep going.

So how do you thread the needle between being aware of the mechanics of writing and ignoring them enough to focus on your characters?

During the discussions on last month’s article (thanks, Don), I came up with a metaphor from my life as an organist. If you’ve ever seen a gifted organist working at full throttle, both hands busy on two or more keyboards and both feet going on the pedalboard (this is NOT me), you can see that the instrument demands good technique. But when you play, you can’t think about which finger to put where or whether to use heel or toe on which pedal. Instead, you have to be focused on the music – on hitting the right balance between the various voices or building a phrase toward resolution. But all that technique still has to be there, buried in your muscle memory and at work even though you’re not paying attention to it.

When I’m learning a new piece, I eventually reach the point where I can, as one of my former instructors put it, “bomb through it.” I’ve gone over the whole piece slowly often enough to get an overall sense of what the composer was trying to do. I’ve repeated some of the tricky passages until I can stumble through them. Then it’s time to take the whole piece more or less at tempo. And the idea is just to keep going, no matter how many wrong notes I hit, no matter how much it sounds like a train wreck. Just forget technique, forget problems, and stay with the music, feeling it come to life, getting to know it.

My wife once attended a series of writing workshops given by Madeline L’Engle. For one exercise, Ms. L’Engle told them they could think about their story for as long as they wanted. Then they had simply to sit down and write as fast as they could for an hour and a half. Essentially, they were told to bomb through it.

This is what first drafts are like. You should have already developed your writing techniques – from reading good literature and books on writing (or the good advice you get here), from talking to fellow writers, from asking questions on Writer Unboxed’s Facebook page. Then you forget about technique and focus on your characters and where they take you, trusting that you know enough to stumble on through. There will be plenty of time later to come back and clean up your story so that it works more effectively. But your first draft is where you learn what the story really is, where you first get to know it. So just keep going, no matter how awkward the writing feels or whether you’re leaving plot threads hanging. Just bomb through it.

Just write the damned book.

So let us hear your stories of first drafts that have hung fire. Or times when your story has headed off in a new direction as you wrote it.

Just yesterday I tore the imposing calendar from the large cork board beside my desk. It was taking up too much space and had been of little help “planning my progress” anyhow.

While writing my first book, I had once scribbled a note with the message “Put it simply” – a reminder that I was crafting a no-frills tale of resolute characters soldiering through a tragic time (as people sometimes must).

Your post today reinforces my first instinct while removing the calendar. After finishing a new scene this morning, I’m returning home. I know what’s replacing the calender now, a note that reads “Write the Damn Book.”

Sometimes the best motivation is a kick in the ass. Thanks, Dave.

Congratulations on losing the calendar, John. I do think that, the more you write, the more confident you become, and the less you have to rely on outside motivators, like deadlines.

Now write the damned book.

This is an excellent description of the balance we strike in that first draft. Writers should strive for a certain level of “muscle memory,” and we should be pushing that level all the time, but not during the actual writing of the first draft. We build those muscles during the other drafts and as we read great books. During the first draft, we just fly hard. As a result, we may write something at the end that turns on the light bulb for a section at the beginning, or discover a whole new layer to a character that we’ll have to go back and weave in later, but that’s okay. That’s why we have second drafts.

There’s another advantage to fast first drafts that writers sometimes forget. The second draft tends to be about big changes: moving big pieces around in your story, adding new pieces, or cutting sections altogether. It’s a lot easier to cut that unnecessary chapter when you flew through it to start with. You haven’t slaved over every sentence and word, so you’re not unfairly biased toward that dead weight. That’s when writers have trouble killing their darlings. When that dead weight is just so beautifully written.

Thanks for a great post.

I like the connection between bombing through it and killing your darlings. I hadn’t seen that.

Thanks, Donna.

I have a grandson who just starting walking, and he ‘bombs through’ every room in the house. Every few days, he’s a little more sure of himself, looking ahead instead off down. Falling less, seeing more. So, we ‘get our legs’ by learning craft and technique. For me, it takes a while for these things to melt into the interior. But once they do, I can stop thinking about which foot I pick up first. A recovering Pantster, I’ve discovered the joys of an outline. But side roads are where the treasure often lay. I think this whole process reveals us to ourselves, shows us how our brains work. I think of drafts as the layers I need to peel away so that I finally get down to bedrock.

I’ve been taking note of how different my novel is from what it was in its early stages. Which elements stuck, which ones expanded, which ones fell away, and also of how the revisions have expanded the story forward and backward ( and up and down) in so many way. Thanks, as always, for a wonderful post.

Sounds like you’ve got it, Susan. And I like the toddler metaphor.

Very refreshing, Dave! I especially like getting permission to bomb through it without an outline because I’m still in the discovery phase as a novelist. I can no more plan out what my characters will do than I can plan what my grandkids will do. They have lives of their own and I only follow them around, taking notes.

Until the time comes for some discipline. Then I have to take control. I’m thinking the same is true for my characters… Hummm…. I’ll bomb through that, too, when the time comes. And I’ll undoubtedly think of this post and smile. Thanks!

Dave–

Porter Anderson’s post for May 15 was titled “The Dreaded Training Debate: What If It Can’t Be Taught?” It “provoked” more comments than I have seen for a Writer Unboxed post, and Anderson answered each of them with painstaking respect for each commenter’s thoughts. Clearly, speculating on whether writing can be taught was analogous to tossing a cherry bomb into a hornet’s nest.

As I read it, your post today, “Bombing Through It” takes up some of the same questions. I have one suggestion to add to your excellent advice. It’s a fast-and-dirty solution for how to bomb through a first draft.

1. The writer must first have the kernel, the seed for a novel, and it needs to be fleshed out some. Not outlined to death, but more or less coherent in terms of a whole narrative. Subject of course to change.

2. The writer makes a short list of her favorite books in the genre she sees her story fitting into. She picks the one she most admires (she probably knows which book this is without a list)–and she rereads it. Then she reads it again, but this time she conducts an autopsy, a dismemberment of the novel in every aspect she can think of–especially plot, character, setting, dialogue. She keeps track of it all, using a notebook, software, etc. The process will probably require further re-readings. In short, The writer internalizes the book. As Tony Soprano might say, by the time she’s done, the book will be dead to her, she will have murdered one of her favorite reads, but it couldn’t be helped.

3. She uses the knowledge as a template, and slavishly imitates this book’s structure–not the voice or style–to bomb through her own first draft. Freed from having to contend with technical questions, she doesn’t complicate matters with how-to manuals. The book she loved enough to marry and murder meets those needs.

4. Having bombed through, she walks away from her story for as long as possible. I would say at least a month. In this time, maybe (or maybe not) she reads one or two of the best of the how-to authors (ideally, she has by this time found a reliable editor). When she comes back to her manuscript, she starts refining her story, and thereby makes it more her own.

Mission accomplished. The writer has finished a novel with good bones. And she now has a place from which to roam in other directions.

Hey, Barry,

Confession time. I don’t normally read other posts on writing, here or elsewhere. I have tremendous respect for the intelligence and insight of my fellow contributors — I’ve seen it in the comments often enough. But I’m a little afraid of an echo-chamber effect, where we all talk about the same topics in the same way because we read each other talking about those topics in that way. So I try to hold back a little so I can base the advice I give more on what my clients seem to need to hear.

Having said that, I just went back and reread Porter’s piece, and I’m glad I did, even though it opens up a couple of cans of worms.

I teach writers for a living, so of course I think writing can be taught, but only within limits. This is why I always make the distinction between technique (which can be taught in general terms) and story (which is wholly individual). When I write posts like this one (and you’re right, it comes up again this month), I present my advice as tools rather than rules (as I do here). When I work with individual clients, I’m able to tailor my advice specifically to their stories, teaching them the techniques they need to create the story they want. When I do it right, it’s empowering.

I think a lot of the false teachers that Porter and Agent Orange call out are trying to teach writers what kinds of stories to write. That can’t be done, at least not effectively. If you’re building your plot around twelve tension bullet points, then you’re not really the one doing the writing — it’s more write-by-numbers.

And as to self-publishing, it’s absolutely true there are a lot of questionable companies out there pushing it as a route forward for writers who don’t yet deserve to be in print. I’ve read several critiques of the shady statistics behind the Author Earnings reports. That’s why I discourage my clients from self-publishing and never promise them that they can publish. I only promise them they will learn to write more effectively.

Which brings me, at long last, to the technique you suggest. I absolutely agree about the value of reading one beloved story several times, so you can analyze how the author does it. I first learned a lot of what I know about plot from multiple readings of favorite writers. But . . . each story is unique. Using another book as a template for your own, even subconsciously, is probably a little too restricting. Your template book is not a single, unified pattern — it’s a combination of many different techniques working together. Chances are good that not all of those techniques are going to fit the story you want to write.

One final point about something that came up in the discussion on Porter’s article — I don’t think published, successful writers necessarily make effective teachers. They publish because they have mastered one set of techniques that fits the kinds of stories they write. Those techniques won’t necessarily fit the story you want to write. A good editor is familiar with a wide range of techniques and can help you find the one that is best for you.

And thank you once again for showing that the most interesting ideas often come up in the discussions.

“Tools, not rules.” God I wish I’d said that.

Or… “Rules for tools”. Basically the same message, sorta.

Dave–

I don’t think it makes sense to reply to replies, but you have responded to my comment at such generous length that I will break my own rule.

For you to say that as a professional editor (and a very good one) you offer “tools, not rules” is a little disingenuous. People don’t seek you out and pay you serious money in order to gain access to a shop table arrayed with socket wrenches and screwdrivers for doing their own novel tune-ups. They are paying for wide and deep experience that translates into guidance and direction of the kind they can have confidence in. Of course, your client writers decide whether and how to use what you teach. But they wouldn’t hire you unless they had pretty much made up their minds to act on your advice. Why else bother?

About internalizing a template based on a single book: I should have mentioned Harry Crews: he’s the one who first put forth this approach. But with or without such a template, voice and style must be the writer’s own–which is what I said. Aping those attributes of a well-known writer is the stuff of parody.

As for discouraging your clients from self-publishing, I wonder why. Certainly, you have an obligation to make clients understand when a novel isn’t ready to see the light of day. But that said, you especially must know that without referrals from known quantities in the business, query rhymes with dreary, and the whole agent search process is dreary indeed. And lengthy. And by no means reliably connected to merit. If you agree with this, then I can’t see why you would discourage your clients from self-publishing.

Hey, Barry,

You know, I did once have a client who paid for my advice and then took literally none of it. Mystified the heck out of me. So, yes, people do come to me to learn how to change their manuscripts.

But I’ve also had clients who simply did what I told them to do mechanically, without really seeing how the changes affected the underlying story. And the results are as uninspiring as with the client who did nothing.

What I try to do — and I think this is the editor’s art — is to see the story the client is trying to write, then to either introduce them to more effective tools or show them how to use their current tools more effectively. What I’m looking for is the a-ha moment, when they can see how to bring their story to life. Perhaps the greatest compliment I ever got was from a client who wrote, “Until I read your report, I didn’t really know what my story was about.”

As to whether or not to self-publish — yeah, it’s an ongoing problem. I do recognize that it’s often the right approach for some writers. There are fewer and fewer traditional publishers — especially the big ones — willing to take a chance on a new voice. So the search for an agent and publisher is often long, heartbreaking, and as you say, tedious. But many writers don’t realize that after they’ve self-published, the battle to get their story into the hands of readers can be equally long, heartbreaking, and tedious. Building a writing career is a long, tough fight, and I try to prepare clients for it so they won’t be discouraged.

By the way, I recommend replying to replies. As I’ve said, I always learn a lot through polite, respectful, intelligent conversations like this one.

Spot on, Dave! Stories are “organic”.

What you describe is exactly what happens to me. I have some general idea and sometimes even go to the bother of jotting it down in the form of an outline. But once I start writing, the “thing” takes on a life of its own! I haven’t yet written a book that didn’t veer off into another direction, pushed by the “logic of the situation and characters” – often a direction that I hadn’t seen coming when I started. So it’s as much a surprise to me the author as to it must be (I hope!) for my readers…

And that’s the fun of it! That’s the real (secret) pleasure of writing (which otherwise is a terribly lonely occupation…) I love “bombing” through it! Then comes the harrowing task of editing the first draft. But that’s nice too, in another way, particularly if you’re a perfectionist (like me).

It is fun, isn’t it? And you’re right, I do think that joy of watching a story take shape under your hand is one of the main draws of being a writer.

I seem to be sticking with the pipe organ as a metaphor this month. Playing the organ will never be my day job — I’m not nearly as skilled as Ton Koopman, the performer in the video link above. But I have played the piece he plays, Bach’s Little Organ Fugue in G-minor, not as fast as he does or as skillfully. But, by God, is it fun when you get it rolling.

This is not to say that I don’t think writers should aim for publication. I’d just like to acknowledge that the act of writing is often an end in itself. And, I suspect a lot of writers would be more likely to publish if they focused on the joy of creation than on pleasing the market well enough to publish.

Every first draft I’ve ever written has taken me down a surprising path as the story has developed. You can outline until the cows come home, but you never really know what your characters are going to do until you start putting words on the page. The first draft is where you explore the possibilities. The second draft is where you sharpen the focus of the story. There’s a lot to be said for “bombing through it.” That’s why I enjoy NaNoWriMo so much. There’s no time to procrastinate. You have to get it done. Thanks for a thoughtful post.

That’s exactly what I’m talking about, CG. Thanks.

Dave, I love this post so much! Especially today. I just rec’d a rejection and it’s the impetus to start a new book that’s been percolating for a while.

How lovely to know you play the organ! Right now we’re practicing Mozart’s Missa Brevis in F for Corpus Christi so I totally get bombing through it. It’s only been in the last week that we are having full practices instead of sectionals and boy, when you get everyone together, talk about having to find that balance and blend and musicality.

Thanks for the encouragement and advice. The first novel that I ever got to a submittable level was one that I bombed through, so I know that’s how I should write one, not in fits and starts, as I wrote the other.

I think it is how it’s done, Vijaya. It’s so easy to get caught up in technique that you forget that the story is what it’s all about. It’s only when you are focusing on your individual story that you can really bring something unique and wonderful (and, one hopes, publishable) to life.

As a musician, I identify with the organist metaphor but also would reinforce that the great organist achieves that ability to just go with the music through practice.

I could play by ear as child, which allowed me to fake my way without practicing. I went straight to the melody, and later, could hear the chord structures moving underneath. I could sing and play a variety of instruments but never really mastered technique to the level I needed to become a professional.

Writing the first draft of a novel takes me a good two years. Then I fly.

Oh, practice is definitely a large part of it. The techniques you need to bring to a pipe organ are literally muscle memory in a way that writing techniques are not. You can only learn them by doing them over and over until they become automatic.

Funny how information you seek arrives exactly when you need it. While I was editing my WIP yesterday I realized my story is much simpler now than in previous drafts. It started out simple, too simple—boring to be honest. Then I started attending conferences and reading books on craft and I believed I needed to apply ALL the advice I absorbed. After all I was serious about this “writing thing.” So my 300+ manuscript blew up to 832 pages. Yikes! With patience and persistence the story has returned to 300+. Whew!

I’ve never needed to Bomb through to finish a manuscript, but I have needed to Bomb the Heck Out Of It to uncover the simple story that was meant to be told. It’s so easy to get lost in the mechanics of telling the story rather than communicating the story. From here on I’m going to remind myself that, “It’s just a story. And that which grows simplest, grows best!”

Thanks for the inspiration, Dave.

I’m curious, was the final 300+ pages better than the initial 300+ pages? I know that stories often benefit from overwriting — your characters and world can feel a lot more complex if you know more about them than your readers do.

Good Point. The two 300+ manuscripts are at opposite ends of the spectrum.

The first: boring and poorly written. (The same goes for the 832 pager, which was bogged down with backstory—my interpretation, at the time, of what it meant to show motivation. Learning how to expose my character’s current emotional turmoil has been my biggest obstacle.)

The second: suspenseful and lean in flesh. The difference in my writing is clear and for the first time in my journey, I’m no longer embarrassed to let others read it. Makes the future appear bright.

You know, I suspected as much, Jocosa. As I say, you can often get to know your characters and story better by overwriting it. Then, when you pare it back down, they will emerge as much more lively.

Maybe next time, you can start by bombing through the 800+ page manuscript, then cut it back down to where it should be?

Thanks for a timely post! Unaware of the name, I began the “bombing through it” method a few days ago. Do you think the bombing idea can be taken too far? I find myself in stream-of-consciousness mode, not even using quotations or proper notation. If the draft is overly messy, I will be discouraged from making rewrites so I’m going to try slowing down, using more show than tell, and being more detailed as I go. I would appreciate thoughts on how extreme the “bombing through it” should be.

As I said once a little while ago, the only time you need to worry about your writing process is when it doesn’t work (Process and Product). So if just bombing through it makes it hard for you to rewrite, then maybe you should back off a little.

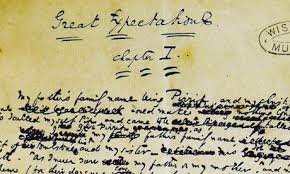

Having said that, I think messiness is a necessary feature to first drafts — see Dickens’ first take on Great Expectations above. It might be more effective for you to get used to wading into the swamp of your first draft with a machete.

Oh, hark how the metaphors fly.

Preach it, brother!!

Hi, Dave:

First, I kinda have to chuckle. So, you never read other posts about writing here. Hmm. Because I always make a point of reading yours!

Sigh…

I love your application of this concept to both the plotter and pantser approaches. I’m a tweener of sorts, always doing an elaborate step sheet/outline that will often include scene sketches and even snippets of dialogue, lines I hope to use, etc. But this is often just to get the story “in my bones.”

Once the writing starts it has to move of its own accord, for that unique, focused time of just plowing straight ahead. I don’t obsessively follow my outline — except to get my bearings if need be. I improvise, to continue with your musical metaphor. The scene weave and forward momentum have to be organic, guided by intuition not logic (in the arid mechanical sense).

And yet, when teaching, I always remember that every student’s process is unique. Mine works for me. It’s not a guide, merely an example.

I agree with you that every book is its own. Slavish obeisance to another book’s structure, no matter how wise, is a misstep.

Finally, as to Mr. Clancy eloquent advice — “Just write the damn book” — if only someone had mustered the stones to respond. “Then edit it!”

One reason I came clean about not reading other posts is that I didn’t want other contributors here to think I was snubbing them by not getting involved in conversations in the comments on their posts. As I say, I really appreciate the give-and-take I get on my own columns. I just think I have a better chance of bringing something original to the venue if I base them more on the give-and-take between myself and clients.

There are also time constraints. I have a garden to get in — I’m going out now to put in pea sticks and clean out the raspberry patch. I’d be putting in tomatoes, but we’re under a frost warning for tonight. This is New England, after all.

Thanks for waving the Go Flag. Even though you teach writing you are saying Yes make a start– the road is wide open. Reading too many how to articles is paralyzing. You can’t gun your motor and follow a direction. Rough drafts are often rough but shot through with some gold. Thanks.

Yes! Just write the damn book. It’s interesting to me that most of us have no trouble or hesitation in describing a vacation trip to our listener friends. No one is paying attention to a word count, a layout, or grammatical sins. Everyone is concentrating on story. Imagine that. STORY.

I think that’s the key, Ray. Just focus on the characters and the story and you’ll find your way through.

Or, as Raymond Chandler once put it, “Throw up in your typewriter every morning. Clean up every noon.”

This post is one of the most inspiring I’ve read here. Your wise words reminded me of oil painting. I was once happily lost in autopilot, intuitively achieving the exact colors I wanted, when an instructor came along and encouraged me to use more of one of my colors. She described it as mushroomy. She asked how I’d mixed it. I had no idea. I tried to duplicate it for a while and gave up. I felt a bit like the caterpillar you mentioned. I couldn’t paint that color again for the longest time. It was gone.

I hope the caterpillar walked again after taking some time to feel her old self, trusting her legs to take her exactly where she’d been going all along. I’m happy to report that elusive mushroomy color reappeared one day, out of the ‘blue.’

Playing music, writing a novel, and painting have so much in common. Thanks again, Dave.

Thank you for the perspective from another of the arts.

I recently heard a program on the radio — probably Radio Lab — that explained that sense of losing yourself in terms of brain chemistry. Apparently, there is a limit to the amount of information our brains can process at once. When you’re fully engaged in an artistic endeavor, whether it’s writing, painting, or playing music, your brain is so involved that it stops tracking your own self awareness. You literally forget you are there.

As I say, there are a lot of reasons to write. But that experience is definitely one of them.

Thank you so much for this article, Dave. It’s just the permission I needed, and will happily resume “bombing through my draft.”

Nothing to add to the ruminations and dissections above – it’s all been said. Just thank you for an excellent post.

Perfection. From the very first word through “The End”, I want a perfect story. No mistakes. No second guessing. Is that so much to expect if you have the audacity to proclaim yourself a writer?

You see, there’s this nasty, snide, demanding little editor, with a very sharp pencil, living in my head. My writing sessions go something like this: Poke. “You know there’s a better word to use there.” Poke. “Seriously? Have you ever heard someone talk like that?” Poke. “Do you really want a comma here?”

“Just write the damn book”? Poke. “Sure. Go ahead, just write it, if you want people to laugh at you or pity you. I can hear them now: ‘Poor Carol. I never knew she was so delusional. What on earth made her think she could write a book?'”

I protest, “But, it’s just the first draft. You know . . . like Anne Lamott says . . . it’s okay to write a shitty first draft. I’ll get the basic story written and then fix it later.”

Poke. “But what if you forget something? Or, what if you DIE before you get it fixed? Do you really want your children and grandchildren to see this?”

In the two and half years since I began this project, this quest, I’ve stumbled over my own anxieties so many times my psyche now limps to the laptop. There’s nothing like writing a book to magnify all one’s flaws and fears.

“Just write the damn book” sounds so sensible–and so easy. But for the novices among us . . . .

No, Dave’s right. There is no ‘but’. It’s time to bomb through it. I just need to shoot that little editor. Or, at least, break his pencil.

First, however, since I’ve been away a few days, I’m going to see what Porter Anderson said that provoked so many comments.

Yeah, I think that little editor in your head is your enemy. You really need to lock her out of the room.

Also, to lift a truth from a different context, it gets easier. As I said, a lot of your anxiety might be coming from genuine weaknesses in your technique. But technique is precisely the part of writing that can be taught. And one good way to learn it is to write a terrible first draft, then go back and edit it.

And if you’re worried about your heirs and assignees finding a bad draft, you can always password-protect it.

I am going to try the ‘bomb through it’ approach for my third novel as I’ve realised that my ‘outline to death’ approach strangled the story in my other two!

The same happened with characters. I knew so much about them before I started writing that they had no room to grow and change.

I’m interested to see if having a loose outline and just writing the first draft makes for a better novel.

Thanks for the post.

You’re welcome, Mandy.

You might want to check out the earlier article I linked to above, about Process and Product. You might find it helpful.

Thanks, Dave. This was great.

Good advice, Dave. I’ve been telling myself that for a month now as I try to complete 18 months of work with that inimitable last three chapters.

Bombing through things is indeed the key. The Unconscious Magic of the mind cannot and will not get to do its thing otherwise. I’d say for whatever reason that’s what I’m afraid of in trying to finish this work. An utterly counterproductive approach to finishing.

I am writing your words on a sticky note and either placing it on the wall in front of me or my forehead. Not sure which one. Maybe both…

You may actually have turned up another reason people get hung up on first drafts, David. Finishing a novel can be a little depressing. Heck finishing reading one can feel like you’ve just lost a good friend. And one possible solution is to simply gird your loins and bomb through it.

Good luck.

That’s a great piece. I enjoyed reading your article, Dave!

Thanks for a great metaphors:)