Character Cue: Whose Line is it Anyway? An Easy Exercise to Strengthen Voice

By Katrina Kittle | May 1, 2015 |

Voice is one of my favorite aspects of craft to play with and talk about. Voice was the subject of my very first post here at Writer Unboxed. Today’s post will be short and sweet—a nifty, easy peasy, so-simple-it-seems-stupid trick to strengthen voice in revision.

When I’m helping someone with a manuscript, I sometimes find that unique and distinctive character voices are inconsistent—the writer will create a memorable voice for her protagonist…but will then allow that voice to disappear for long passages of the story. Usually, the voice will be strong in passages containing dialogue, but will lose its edge at other times. Contemporary writers, for the most part, tell their stories using first person or third person subjective as their chosen style of narration—and in both of those cases, the narration should be filtered through the point of view character’s voice and should remain strong and present throughout. A helpful little trick I was taught along the way can help with those inconsistent, “voiceless” passages—infuse some “character cue.”

You infuse character cue by tweaking the passage so that it contains some flavor, some vestige of voice, through character attitude and tone.

[pullquote]You never want a line of narrative that could have been delivered by just any ol’ character in your novel, right? Ideally, you want every line to be imbued with that strong voice so the reader knows exactly who spoke it.[/pullquote]

Look at it this way: you never want a line of narrative that could have been delivered by just any ol’ character in your novel, right? Ideally, you want every line to be imbued with that strong voice so the reader knows exactly who spoke it.

For example, perhaps you’ve hit a point in your story where you wish to convey to the reader that a horse trotted across a field. Your point of view character is going to tell the reader this. But if you write “The horse trotted across the field,”…well, anyone could have said that, right? There’s nothing in that line that cues up the character for us as readers. Now, I know, I know: that’s a mighty short phrase, and you might very well have a phrase like that and it would be just fine—as long as it was buried in context and in surrounding sentences that were loaded with distinctive character voice.

But if you write, “The damn horse trotted across the field like I was invisible,” well, then, that’s someone talking to us. That’s not just anybody—that’s a particular somebody with a specific tone and attitude.

And if you write, “Of course the horse trotted across the field—what else was the poor thing to do?” that’s an entirely different person, isn’t it? We still have the horse moving across a field, but now we also have voice and characterization. And isn’t that our goal—that everything we write does double (or triple) duty and fulfills more than one function?

If you comb through your manuscript seeking places where the narrative is journalistic or neutral, and then you rewrite it so that it is steeped in character cue, you can keep voice present and strong throughout.

I do that exercise with writers of all ages—I ask them to pore over two or three pages of their work and pull out the lines that—on their own—don’t sound like they belong to any specific character. If the writer finds a line that anyone could’ve said, they revise the line to contain character cue.

I find this stage of revision comforting. This is the kind of work that comes after the terrifying, crazy-making stage of deep revision—cutting and combining scenes, cutting and combining characters, writing new scenes. This is the kind of work to embrace when you’re certain (well, as certain as we ever are) that the story’s essential skeleton is assembled and will no longer change drastically. These may seem like small, inconsequential touches, but the accumulative effect of strengthening voice throughout your entire work will make your novel much more polished and professional.

I plan to offer a few more simple tricks as well as go much more in-depth into both Point of View and Voice in my upcoming online class beginning May 28th (details at www.onliten.com if you’re interested in joining me!).

Just for fun, rewrite that horse trotting sentence so that it’s imbued with character cue for one of your own characters.

The horse trotted easily across the field, and I felt the roll and bump as though I were sitting astride the glowing bay.

Thanks, Judith!

This is Andrew, watching the horse he’s ridden for the past two months, while filming, leave the set for the last time. Stephen and his family have been watching the movie’s battle scene.

———-

“Where’s your horsie, Mr. Movie Man?” The boy Stephen’s upturned face was full of wonder. Inviting them was the right move.

He reached down and swooped the child up, rotated and pointed to the far side of the field. “Do you see that covered box, there, by the blue truck? Where they’re loading the cannon on the flatbeds?”

The boy nodded.

“That’s Alhambra’s. He worked hard today.” Hierarchy was setting in: crew and cast went through the same battle—only everyone else, including Grant, had work to do. Except me. “He’s going home now.”

“Are you going home?”

“Soon, lad. Soon.” Too soon. The reenacters had walked off arm in arm to head for their local pub—and their familiar conversations. He would have been the center of attention had he shown, was not missed at all when he didn’t—he’d made that mistake before, been pitied by the extras—ouch, when George explained it to him. The end is beginning.

“When do you ride the horsie again?” The child’s face was inches from his.

“The next time we’re in a movie together.” Never. But the boy would have no concept of ‘never.’

———

Pride’s Children, Chapter 18

Thanks, Alicia!

I found my way to more character cues by accident in a recently completed manuscript. In previous versions I had featured character thought in italics (as do many of my favorite authors in my genre – epic fantasy). I’m not even quite sure where I got the idea (I think from another post here at WU), but I wanted to incorporate that thought into the narrative. Doing so made me focus on “all” of the narrative as coming from each particular POV. I enjoyed it. And I don’t think I’ll be going back to italics. If it’s all from the POV character, why bother? Thanks for the reminder.

Excellent, Vaughn. Great point!

I use the italics to convey distance: italicized words (few) are the closest I can get to expressing a character’s direct thoughts.

Since, in each pov (I have three), everything is described by the current character, I have a lot of internal monologue that shows how the character views the world, but is indirect.

When I need to express something in the exact words thought by the pov character, I use the italics – and switch modes to first person.

In the sample I provided above, the italics were eaten by the cut-and-paste, and I couldn’t figure out how to put them back, but ‘Inviting them was the right move.’ and ‘Except me.’ should have been italicized.

I keep the direct, italicized mode to a sentence or two per internal monologue. It works for me.

It wouldn’t be necessary in first person, and maybe not with a single third-person character, but I find it gives immediacy to being in the pov character’s mind that is far superior to using, ‘he thought’ after a direct though.

YMMV

Was that a horse in that field, or a donkey? David kept to the tree cover as he crept closer. A horse. Which meant Philistines, which meant raiders. He sprinted back to the village to raise the alarm.

Ooh, intriguing. I’m hooked!

Thanks Katrina. Great article!

The smell of hay and manure filled my nostrils and I knew: there must be a horse nearby. Great, just what I needed, another darn horse who’s got no business prancing across the field like he owns the place.

Lovely, Sue!

Katrina–yours is an important topic, and you offer useful suggestions for how to make characters sound like themselves. I especially like the exercise you use with your students: find places in your story where what’s said (or thought) could be said by anybody, and re-write in the voice of a particular character.

But: “This is the kind of work that comes after the terrifying, crazy-making stage of deep revision….” Here, we part company. For me, focusing too much on plot or organization at the beginning leads to the one-size-fits-all voice. I think it’s important to have a good sense of one’s characters at the beginning, in order to draft a story using their unique voices. Of course, there’s always lots of backing and filling later, but if the writer knows her cast, can hear and see them up front, there should be much less need to fix something so important later on.

Thanks again for a solid post on a key issue facing any writer of fiction.

Thanks, Barry! And, actually, I don’t think we part company at all. I didn’t mean to suggest writers shouldn’t work on voice until late in revision. Everything I do in my writing classes begins with knowing the cast–I thoroughly agree that this heavy lifting up front means less to “fix” later. I simply meant that this particular easy exercise is perfect for the late stage combing through and seeing where your strong character voice may have “dropped out” for a bit. Happy writing!

Katrina, your advice echoes mine to my clients and blog readers, and is what I strive for in my own manuscripts. Another technique for injecting voice into narrative is what I call “experiential description” in my book, Mastering the Craft of Compelling Storytelling. In fact, your horse trotting exercise is a good example of using experiential description. I wrote a Writer Unboxed post about the technique back in 2007–here’s a link: https://bit.ly/1JFM9Y7. Thanks for sharing this insight in such a useful way.

A lot of good horse sense, Katrina, and straight to the point. A great big mahalo!

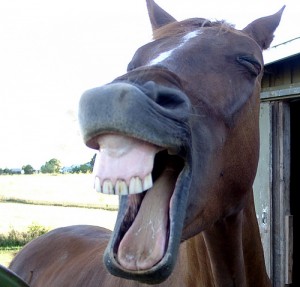

You win a Picture Tweet for this personally beloved pony pic!

Grand post, Katrina!

This is timely advice. I’m at the stage in my revision that I’m trying to solidify the two main characters’ voices. Something so simple as “seeking places where the narrative is journalistic or neutral” is easy to find and highlight. Your examples on infusing voice were wonderful. I love finding these little tools that just click, and make a daunting task seem manageable. It’s one of the reasons I enjoy this blog so much.

She couldn’t believe it. A living, breathing horse trotted across the field to nibble at the flowers, as if it didn’t know that all of it’s kind had been sent to the colony planets fifty years ago.

The horse was regal, tail held high, as he trotted across the field. Of course he was an Arabian. He was proud and did what was expected of him. We were kindred spirits. I understood him completely, even if no one else noticed.

Also, I have a question. I understand that each character has their own point of view voice. I am confused with that and author voice. I read somewhere that an new author must write a few books before their authorial voice is perfected, or at least established. What constitutes authorial voice? Thank you!