The Elusive “I” in PI

By David Corbett | April 27, 2015 |

Despite having worked as a private investigator for fifteen years, I had no interest whatsoever in writing a PI novel until recently. (My most recent novel, The Mercy of the Night, published earlier this month, has a quasi-PI, legal jack-of-all-trades protagonist – more on him shortly.)

The reasons for my reluctance to plumb my own professional experience were simple enough.

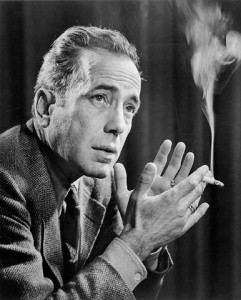

First, none of the PI novels I’d read, even the best – including Chandler’s, Hammett’s, and Ross MacDonald’s – bore much resemblance to the work I’d done as an investigator, though MacDonald’s came closest.

From what I could tell, readers expected their PI protagonists to be something akin to the plains gunmen in an urban setting, and that was as far from my own experience as imaginable.

For the most part – the part that would best lend itself to a crime novel – I was a cog in the justice system, a “people’s pig” who tracked down witnesses and sifted through evidence on behalf of criminal defendants to keep the prosecution honest.

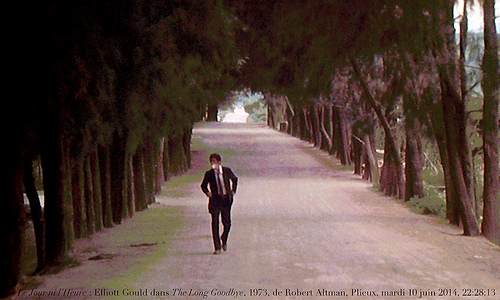

Despite the job being by far the most interesting I’ve ever had outside writing, the vast majority of what I did wasn’t the stuff of action-packed thrillers. The work resembled more that of a reporter than a gunman – finding people, talking to them, writing it up – and I was only in physical danger once. (Ironically, the guy who tried to kill me was a doctor, but let’s put that aside for the moment.)

Second, it became pretty clear in my reading through the genre (and listening to agents, editors, and readers) that when it came to crime no one much cared to hear from the defense table.

It did seem that readers would at least tolerate hearing from the criminal himself, however, and that also seemed to provide me more juice as a writer. I found myself far more excited telling the criminal’s tale than belaboring the investigative steps taken on his behalf once he was caught.

The result was The Devil’s Redhead, with a hero based on several pot smuggler defendants I’d helped represent over the years, and that was as close to my own PI experience as I got for the first four novels.

After that, I chose as my protagonists a cop (Done for a Dime), a bodyguard (Blood of Paradise), and a Salvadoran-American teenager smuggling his deported uncle back into the US (Do They Know I’m Running?).

I was pretty happy with those books, and they were well-received critically. (One was a New York Times Notable book and was called “one of the three or four best American crime novels I’ve ever read” by Patrick Anderson of the Washington Post, another was nominated for the Edgar Award, etc.).

But then in conversations with Charlie Huston, Don Winslow, and Michael Koryta, I began to reconsider my aversion to writing a novel based on my former calling.

When I told Charlie my job had been interesting but not the stuff of cliffhangers, he asked me to describe the most challenging thing I’d done. I told him about having to be the guy who goes to the door of the family of a murder victim with the hope of finding someone in the house who doesn’t see much point in having the killer – my client – executed. Charlie replied simply, “I think that’s interesting. You should write about that.”

Don and Michael, both former PIs themselves, thought I was turning my back on a goldmine of material. When I told them the rough idea I had for the next book (which would ultimately become The Mercy of the Night), both expressed genuine enthusiasm for the idea.

[pullquote]I wrote a book called The Art of Character that, in a chapter titled “Protagonist Problems: Stiffs, Ciphers and Sleepwalkers,” addressed the very problem I encountered: basing your protagonist on someone too much like yourself. [/pullquote]

Also, by this time I’d read more in the genre and realized I’d given short-shrift to the suspense inherent in a good investigation – finding the truth is a tricky business, regardless whose side you’re on – and I trusted my own instincts as a writer a bit more. I felt, at least, up to the task of trying.

The challenge proved far more daunting than I’d expected, for reasons I hadn’t foreseen.

And I should have. I wrote a book called The Art of Character that, in a chapter titled “Protagonist Problems: Stiffs, Ciphers and Sleepwalkers,” addressed the very problem I encountered: basing your protagonist on someone too much like yourself. Perhaps I believed that having written so sagely on the topic I was somehow immune to the affliction.

Oh, the folly.

I learned the problem with Write What You Know is that you can easily assume something is on the page that isn’t. And the reason for that is because you just implicitly understand its presence without double-checking to make sure the reader is equally aware.

[pullquote]I believed that having written so sagely on the topic I was somehow immune to the affliction…. Oh, the folly.[/pullquote]

Two of my early readers just couldn’t connect with my PI protagonist, which was somewhat humbling since he bore such a strong resemblance to Guess Who. (Might I also lack that compelling je ne sais quoi, I wondered. “Don’t ask,” my wiser half replied.)

And so I learned firsthand the wisdom of Eudora Welty’s revision of Write What You Know. She advised: Write What You Don’t Know About What You Know.

This was how I realized I needed to make my hero different from myself, someone I recognized but didn’t fully understand, so I would have to discover him.

That act of discovery would ultimately translate on the page into a series of reveals that would intrigue the reader, making her wonder: Who is this man? Why does he get up in the morning? What keeps him awake at night? Who and what does he value and love, what does he fear and shun – and, most importantly why? How far would he go to protect the people and things he cherishes?

By basing the character too closely on myself, I’d neglected all that, taken it for granted. It was a fatal flaw. The character lay there inert on the page.

[pullquote]I learned firsthand the wisdom of Eudora Welty’s revision of Write What You Know. She advised: Write What You Don’t Know About What You Know.[/pullquote]

And so I conjured Phelan Tierney – the oddity of the name alone made me wonder about him. (“The man with two last names,” as one of the other characters observes.)

I made him a lawyer, not a PI, which also required me to raise my game. I’ve known a number of lawyers who’ve traded their bar card for a PI license, and most of them have done so for the simple reason they preferred interacting with people to shuffling paper.

But my own experience with lawyers (including my marriage to one) also made me aware of the distinct habits of mind they acquire. The best combine a bare-knuckle pragmatism with a capacity for logical jiu-jitsu that an algebraist would envy. That too engaged me in a way my bland cipher of a PI hadn’t, and it helped me avoid some of the classic tough-guy clichés that afflict too much PI fiction.

Given these differences I felt okay also giving my hero a few traits I did know a bit more intimately.

I made him an intellectual magpie, curious about everything, from Caravaggio to a Salvadoran flower called loroco – “knowledge that’s a thousand miles wide and two inches deep,” as my former boss put it, describing what an investigator needs to be able to talk to anyone.

I made him a wrestler, who gained a scholarship to Stanford through the sport. (I was never that good, but I wrestled in high school and still follow the sport at the collegiate level.)

I made him a recovering Irish Catholic, for I understand all to well the moral vision that informs that particular corner of the faith.

[pullquote]I ultimately discovered my own personal take on the “man who can walk the mean streets but who is not himself mean”[/pullquote]

Most importantly, I made him a widower. I didn’t do this for the usual reason, to add the gravitas of grief. That, to my mind, is just a cliché.

Rather, from my own experience and that of a close friend who also lost a cherished wife to cancer, I saw how we’d come out of the experience unaware of how it had both made us better men and yet also imprisoned us. I won’t go in to the particulars – you’ll need to read the book – but we both realized we’d developed an inclination for helping women in unlucky straits, unaware we were still stuck in that hospital room, hoping for a better ending.

This was one element of my own biography that, with the help of readers who let me know what was working, what wasn’t, I ultimately managed to render meaningfully on the page. And it became a crucial element of the plot, which concerns Phelan’s obsession with trying to look out for a girl who wants no part of him. One thing those in trouble can sniff out in a heartbeat is the hidden agenda of someone who says he only wants to help.

And that was the unique angle I believe I ultimately discovered, my own personal take on the “man who can walk the mean streets but who is not himself mean,” as Raymond Chandler put it. He’s a hero who represents what I don’t know about what I know – a man who’s carved out a distinct niche for himself in the justice system, likening his role to that of healer rather than hunter or hired gun. He feels a special devotion to those who hope to turn their lives around – or who discover that, for whatever reason, they’ve become invisible, or voiceless.

I discovered Phelan Tierney, who – luckily, for all concerned – isn’t me.

If you’d like to read an excerpt, one was selected as Narrative Magazine’s Story of the Week for April 5-11. A second excerpt was featured by that merry cabal of Iowa Workshop grads known as We Wanted to Be Writers.

Have you ever based a protagonist on yourself? How did that turn out – did you have the same problem I did?

Have you ever had a protagonist that simply didn’t come alive for you the way the more secondary characters did? Why was that? How did you solve the problem?

“I believed that having written so sagely on the topic I was somehow immune from the affliction…Oh the folly.” I love this. It speaks, for me, to the disconnect that happens when you’re in the writer’s seat rather than editing someone else’s work. And especially, as you say, when you’re writing about what you know.

I didn’t consciously base the protagonist of my novel on myself, but as I’ve peeled away layers of her story through revisions, I’ve had a creeping suspicion that we’re related. I think she’s the girl I want to be when I grow up. The distance I’ve placed between us has made it safe for me to burrow deeper. But it has taken a long time, and feedback from a lot of readers, for me to see how I fail to put on the page what I assume is there. The biggest challenge for me is in ‘becoming’ the reader while I write. It sounds nuts as I say it and may explain the headaches, but I think it’s the brass ring.

Hi, Susan:

I loved this: “The distance I’ve placed between us has made it safe for me to burrow deeper.”

This speaks to a very curious and somewhat troubling truth: We don’t want to dig that deep with ourselves sometimes, at least not on the page. IN THE ART OF CHARACTER, I say something akin to: If you’re not willing to be scathingly honest with yourself, do everyone a favor and pick on someone else. I wasn’t (just) being glib. It really is difficult to be that naked in front of the reader, who is, after all, a stranger.

But the honesty is necessary for truly engaging writing, which is why characters prove invaluable in exploring those aspects of ourselves we most likely otherwise would keep hidden.

Also appreciated this: “The biggest challenge for me is in ‘becoming’ the reader while I write.” Stephen Dobyns in RIGHT WORD, RIGHT ORDER calls this “learning to read dumb,” i.e., learning to read the text from the outside, not from within. I’m not sure it’s possible during the actual act of writing, but it’s essential during rewriting. That said, it’s a tricky business, and don’t beat yourself up if you find it difficult. We all do. (Juno Diaz said that the writer will never see the text truly as the reader does, and that’s part of the mystery of writing.)

Thanks for commenting!

David-

In some ways it’s easier to write characters who are completely unlike oneself. Supporting myself with fiction writing back in the Eighties, I bashed out several YA mysteries featuring a famous girl detective.

Was this teenage girl anything like the thirty-something male writing her? Uh, no. Was she an authentic teenage girl? Uh, no, not that either. She was (is) a cultural icon, a well known character drawn by many before and after me. I only had to follow, and slightly evolve, a known quantity.

More recently I’ve worked on characters who are more like me, which is to say male. As you so astutely point out, that doesn’t automatically make them more authentic. We are quite right that we are blind to ourselves, unwilling to see what is difficult to face in our nature.

But that in itself is a gift. There’s tension in not knowing, in needing to discover something. It’s a help both in building character arc and in the writing process itself.

I’ve recently been reading the piece I’m working on to my wife, a former independent editor. (That’s harrowing, but never mind.) She frequently says, “You’re writing about me…(or our son)…(or your ex)…(or you).”

Actually, none of that is true. I am borrowing details and ways of looking at things in order to bring my hero alive. What I don’t understand about him, I’ve made into a mystery for him to solve. It’s my job too, really, and researching his unique psychology has taught me not only about him but about myself and myself as a storyteller.

So, I agree with all that you say. What I’d add is that the discoveries characters go through are our discoveries too. I’m no longer afraid of not knowing everything about someone I’m writing about. Learning it can enliven not only the process but the story itself.

Cool post. Now to check out Phelan Tierney…

Hi, Don:

I was once on a panel where one of my fellow panelists responded to the question “How much do you need to know about your characters?” with the one word reply: “Everything.” And I’ve come to believe that is exactly the wrong answer.

First, we can’t know everything about anything. But more fundamentally, it is exactly the act of silvery that makes the character interesting — both to our readers and ourselves.

I think writing about a character other than myself creates a great opportunity for exploration and empathy. It forces me to look at things differently than I might.

And yes, I’m a bit of a magpie as well, taking little bits of this from someone I know, that from someone else, with a pinch of me, in fashioning a fictional character whose nature I’m still exploring.

Thanks for chiming in. Good luck with “the current piece” (and that harrowing editor at home).

“And yes, I’m a bit of a magpie as well, taking little bits of this from someone I know, that from someone else, with a pinch of me, in fashioning a fictional character whose nature I’m still exploring.” D.Corbett

“I am borrowing details and ways of looking at things in order to bring my hero alive.” D. Maass

Loved these comments.

The fusion of ‘little bits’ and ‘borrowing details’ brings to mind a mosaic or certain of Picasso’s images.

“I learned the problem with Write What You Know is that you can easily assume something is on the page that isn’t.”

Oh, how I wish you’d written this article years ago, in the very early stages of my work-in-progress. I’ve finally come out on the other end of the assumptions—I hope—but it has been on long haul.

Even when you think you’re on top of the assumptions the best way to squash them is to offer up your material to readers at all points along the way. Only outside forces can really tell you what’s happening on the page.

This post is a keeper. One to be read again and again. Thanks for sharing your journey.

Thanks, Jocose. Yes, the great gift the reader provides is she keeps us honest. Sorry to hear the WIP was so challenging, but that’s often the case when something is close to our hearts.

No worries. The greater the challenge the more we grow. Write On!

David–

Pick a card, any card…. Along with so much else to be admired in your post today is your PI analysis of self. It leads you to conclude that the loss of your wives to cancer led you and a friend to be better men, but also imprisoned: “we both realized we’d developed an inclination for helping women in unlucky straits, unaware we were still stuck in that hospital room, hoping for a better outcome.”

That compressed insight illustrates perfectly Eudora Welty’s revised mantra for writers: write about what you don’t know about what you know. You knew everything about your loss, except how it had changed you.

I know this insight leads your character Phelan Tierney to realize why he keeps trying to help someone who “wants no part of him.” That fits with and energizes your own story, but I have to add something: “One thing those in trouble can sniff out in a heartbeat is the hidden agenda of someone who says he only wants to help.” My own experience leads me to a different conclusion. More often than not, being in emotional or spiritual need places people in a vulnerable position. They have a deepened wish to believe in others, and this wish makes them susceptible to exploitation of all kinds.

Thanks again. The scene these days is awash in cartoon violence and make-believe, thumbing its nose at the world we actually live in. You on the other hand write for adults.

Hi, Barry:

I probably overstated the matter. I think you’re right about most people in deep need being easy prey. (I worked the People’s Temple Trial, and am still in touch with some of the Temple survivors.)

Jacqi, the character in question, has been hardened by her family and the street. She’s already been used and used so often — and pitilessly — she finds it impossible to trust anyone, and senses a self-serving motivation to any offer of help.

Of course, this doesn’t make her immune to exploitation. Quite the opposite, she trusts exploitation far more than genuine concern. Getting used and using others is what she understands. She just thinks she’s smart enough to stay a step ahead of whoever is trying to play her. The thing she doesn’t understand, the thing that scares her, is actual kindness with no strings attached. It’s what she secretly, deeply craves. And her arc to recognizing that is pretty much what drives the book.

Yeah, I’m a little weary of the überfantastic gestalt right now as well, though some of it is always fun. I enjoy an unhinged imagination as much as the next guy, if it’s done well — i.e. Kafka, Borges, Marquez, etc. But it strikes me as a little troubling that, at a time when more and more people feel powerless to create any meaningful change, when so many people feel anxious for the future, our culture is awash in vampiric wish-fulfillment, pseudo-medievalism, and paranormal ooga-booga. Realism has come to mean the microscopic examination of the trivial, and it’s hard not to drag out the old Bread-and-Circuses canard.

But that’s another post. Thanks as always for chiming in. Love how you always peel back the surface and check out the machinery underneath.

‘I told him about having to be the guy who goes the door of the family of a murder victim with the hope of finding someone in the house who doesn’t see much point in having the killer – my client – executed. Charlie replied simply, “I think that’s interesting. You should write about that.”’

Is that part of TMofN, David? I’d always be interested in this story, but given the public’s present-day cynicism about the police and judiciary, I suspect the audience would be broad. PI-as-healer is an attractive, hopeful idea in and of itself.

In one of my yet-to-be finished novels, the MC is an MD, but her professional setting and life circumstances diverge enough from mine I hope I won’t make assumptions. Good to be forewarned about the perils, though. Thanks.

Hi, Jan:

Actually, the story about going to the victim’s family’s house will be in another book. (I have written a novella we hope to bring out this summer in which Tierney represents an African American Iraq War vet who kills a much loved and widely respected white cop, and has to deal with the universal condemnation of his client.) But MERCY sticks to the core story thread of Tierney’s attempt to help a girl who senses a secret agenda on her part, with additional complications making it all but impossible for him to help her.

We all hope to base our fiction on what we know best, and I would definitely use your medical background because laymen such as me find it so fascinating — and the intimate nature of the doctor-patient relationship is inherently charged with drama. But yes, making the heroine different in some fundamental way — age, class, race, talent. (I often find making the hero smarter or more talented or stronger than me forces me to raise my game, and elicits that beneficial fear Don has been talking about in a couple recent posts and comments — always a good thing.) Good luck with the as-yet-to-be-finished novel.

BTW, Jan: I just learned that the Phelan Tierney novella — which is titled “The Devil Prayed and Darkness Fell” — has been accepted by my publisher as a Kindle Single. (And my editor said she re-read the ending this morning and wept at her desk.) Though I don’t like making my editor cry, I think over all this is encouraging — and so thanks again for saying you’d be interested in the story of a PI having to plead for the life of his client. Turns out you’ll get a chance to at least read something like it.

Congratulations, David! Let me make a wee prediction based on the premise of a soulful PI, your book’s Amazon rankings at present, and the way disintermediation is helping authors: a Netflix mini-series down the road.

Pie in the sky? Maybe but we shall see… Either way, T & M should do well by you.

David, thanks for the piece about the PI in fiction, and in particular for that insight about the fictional PI as the plains gunman translated to an urban setting. Now I find myself viewing my main character, a PI, from a new angle. For better or worse….

But to answer the questions you pose at the end of your piece: Many years ago, when I first started writing, I wrote a half-dozen short stories based very loosely on some childhood experiences in a small California town. I published some of them in small mags, and once even got a nice rejection letter—not a mere pre-printed postcard!—from the New Yorker’s Roger Angell, every bit as fulfilling as actual publication, at least for a young, naïve writer….

But fact is, for whatever reason, I never found myself as a topic for fiction all that interesting. It turned out I preferred writing about anything but myself, which is perhaps why I ended up a freelance magazine writer, and over the years cranked out six nonfiction books and upwards of 400 magazine articles, not a one of which had anything to do with me, beyond, I suppose, whatever personal sensibilities, biases, and slants any writer inevitably brings to the task, and that inevitably creep into the story. I think the part of writing I like best is the research, thus I can now happily go on at great length on such topics as the Tocharian language, a dead limb on the Indo-European language tree spoken in Central Asia until about a thousand years ago. I suppose like a lot of writers, I use the research as a way of avoiding the really hard task of actually writing. Of course as a freelance magazine writer, a looming deadline and prospect of a paycheck was always sufficient motivation to eventually sit down and write.

Regarding your question about a protagonist that won’t come alive the way the secondary characters do, you bet! This almost always happens to me in my fiction. I suppose it has to do with fear of the main character who, because he — or she — is important, becomes a little intimidating. I feel more relaxed writing secondary characters, have more fun with them, and so they end up more interesting. Thus a secondary character in one novel I’m working on — the one with dead Indo-European languages, in fact — eventually became the main character. And now she’s getting a little intimidating….

Eric!

How nice to hear from you. I actually think your journalism background and my PI background worked in similar ways for us: They gave us a world of things to observe, consider, explore. And both of us had to not just notice but write up what we came across, often under deadline — and I think that’s invaluable training.

I think bringing your own “sensibilities, biases, and slant” to stories about something other than yourself is similarly the best training ground for fiction imaginable. You learn to temper those sensibilities and honor the reality in front of you — just as you also realize you can never escape those sensibilities entirely.

I have a sneaky suspicion I’ve heard someone speaking Tocharian on Game of Thrones…

I think the ease with which secondary characters arise in our minds is due to their so often being types — and types are just what they appear to be, nothing more or less. But main characters, and especially protagonists, demand greater complexity — there’s something hidden about them, and as a result they don’t just step forward like Harlequin and Pulcinella and speak their lines. They’re riven with contradiction and carry the burden of theme and premise. We too often think of them as virtuous and they tend to glow like a dashboard saint. I devote an entire chapter in The Art of Character to protagonist problems precisely because the hero/ine is the hardest character to get right. And even with that background I still had to fumble an falter my way to a good result.

Thanks for chiming in, good sir.

Since he’s an Irish Catholic, I think his parents would have named him Phelim.

Hi, David:

Actually, there’s a reason why it’s spelled Phelan — but you’ll have to read the book to learn what that is. :-)

David, the fact that you actually worked in law enforcement is the best reason for you to write about it and all the various aspects that go into criminal investigations. Since you have that background, I believe your works would come off as more realistic than most. I think people are too used to “CSI” and “NCIS” episodes where crimes are solved with the click of a computer mouse. Personally, I know better, which is why I prefer reality crime shows like “The First 48.” Thanks for your input and keep up the good work!

Hi, Alejandro:

You wouldn’t believe how many cops I know who HATE shows like CSI. It’s gotten to the point where juries think that kind of abracadabra is real. (There’s even a term for it: The CSI Effect.) Officer testimony means nothing — did you do a DNA test on that bag of dope you saw him spit on the ground?

That said, technology is creating incredible changes in investigation — cell phones in particular. But the FBI’s recent admission that they just plain invented years of forensic “evidence” — including in the cases of 13 defendants already executed — takes us back to the fundamental truth: the law is about people. Not abstract rules that exonerate us from the burden and the responsibility of judgment.

Keep the faith, brother.

I don’t even have a desire to write a character based on me. I write to escape me. I WILL NEVER CREATE A “ME” CHARACTER. Well, unless I change my mind.

Unfortunately or fortunately, every character I create will be spawned from the part of my psyche that cannot thrive in the real world.

Corporeal man is not accepting of such creations, but where there is virtual reality, fiction, and progressive fields of lies; there shall my rejected psyche dwell.

In a realm where I am GOD and everyone else is just visiting.

Ah, yeah, okay, I haven’t really finished a character, yet, but I’ll get back to you on this topic.

Hmm, this was thought provoking.

Brian:

You made me laugh out loud, thanks. The weird thing — I didn’t really set out to write a character like me, I just didn’t make enough of an effort to prevent that from happening. The result: a cipher, a stiff, a sleepwalker. That’s the lesson, grasshopper, to the extent there is one.

Simply put, yours is the best article I’ve read on Writers Unboxed. Thanks for the excerpts. I plan to read more of your stuff.

Ray — Wow. Thanks. High praise, given the creatures who lurk in these woods.