Feeding Your Readers Information: A Look at a Master

By Dave King | April 21, 2015 |

As so often happens, the comments on last month’s piece (What Do Your Readers Know and When Do They Know It) showed that there was a lot more to the topic than I could cover in a single column. So I thought it would help to look in some detail at how a master of the craft created tension by how he fed his readers information.

As so often happens, the comments on last month’s piece (What Do Your Readers Know and When Do They Know It) showed that there was a lot more to the topic than I could cover in a single column. So I thought it would help to look in some detail at how a master of the craft created tension by how he fed his readers information.

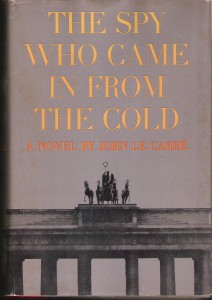

If you’re not already familiar with John le Carré’s The Spy Who Came in From the Cold, the quickest, easiest way to get to know the story is to stream the movie. The plot follows the book very closely. Besides, Richard Burton and Claire Bloom are always a pleasure to watch, and keep an eye peeled for a very young Robert Hardy. If you’d like to check it out now, I’ll wait.

So, The Spy Who Came in From the Cold opens with Alec Leamas, the head of the Berlin bureau of MI6 (i.e. the Circus), waiting for Karl, his last remaining operative, to make a desperate run across the border from East Germany. Karl finally appears but is gunned down before he can reach safety. All of Leamas’ other operatives have also been hunted down and eliminated by Mundt, a particularly vicious chief of the East German secret service (i.e. the Abteilung). So when Lemmas’ boss, Control, offers him a chance to destroy Mundt once and for all, he jumps at it.

Given that setup, le Carré then proceeds to feed his readers information at three different levels of reality: what the world thinks is happening, what Leamas thinks is happening, and what is actually happening.

We first watch level one develop as Leamas comes apart at the seams. He’s given a makework job in accounting at the Circus, starts to drink, is accused of embezzlement and fired, drinks more, and winds up in a grimy apartment working a menial job at a library. There he meets and starts to fall for a young, idealistic communist named Liz (‘Nan’ in the movie). Despite the light she brings into his life, he continues to spiral downward until he assaults a grocer and is jailed. When he’s released from prison, he’s approached by a bumbling East German agent, who has heard about his situation from Liz.

At this point, le Carré pulls back the curtain on the second level. Leamas sneaks off for a secret meeting with Control that makes it clear his disgrace and collapse are a ruse to get the East Germans to recruit him. In this meeting, Control challenges him on his relationship with Liz – it’s out of character for someone spiraling into degradation to fall in love – and offers to help her out. It’s during this meeting that readers also learn, almost in passing, that George Smiley, the Circus’s legendary strategist, wants nothing to do with the operation (a detail omitted from the movie).

Le Carré still hasn’t revealed how Leamas’ staged collapse will lead to his getting revenge on Mundt, so curiosity about the plan will keep readers turning the pages. But they’ve also come to realize by this point that Leamas is intelligent, brave, idealistic, and loving. They care about him, and are worried that he’s essentially turning himself over to the enemy. At the same time, they’re eager to see him defeat Mundt, who has done so much damage to his life.

While all these sources of tension are in play, le Carré slips in the first hint of the third level at work – that there is a plan beyond the one Leamas knows. Leamas thought he recognized the man who set him up with the library job. He asks Control who it was, and Control denies knowing anything about him. It’s a classic bit of authorial sleight of hand – feed your readers clues when you’ve drawn their attention elsewhere.

The Abteilung agents recruit Leamas and take him to Switzerland on a false passport to be questioned by someone from higher up the food chain. From the information that Leamas slips the Abteilung officer – deposits he made to various continental banks under false names, glimpses of certain people talking in the hallways at the Circus, the fact that Control once came to Berlin and met with Karl personally – readers begin to see the shape of the plan. Leamas is essentially planting evidence that Mundt is a double agent, working for the Circus, which will certainly get Mundt killed.

Then – we’re a little less than halfway through the book by now – the third level really comes into play. Leamas learns that someone has leaked news about his meeting in Switzerland, and he’s now wanted for violating national security. He has no choice but to travel to East Germany with his Abteilung contact. While le Carré gives some plausible alternative explanations for the leak – the inept East Germans in Britain, someone higher up in the Abteilung – Leamas is sure Control leaked the information to force him to go to East Germany. He assumes that the leak is intended to make him a more plausible witness against Mundt – that it’s part of the second-level plan that Control didn’t mention.

At this point, le Carré starts manipulating information in a new way – readers begin to learn critical facts that Leamas isn’t aware of. Before now, le Carré included scenes from Liz’s point of view, but they were mostly intended to give readers a chance to get to know and like her. Now readers see Smiley show up at her apartment and offer to help her. Given that Smiley hasn’t been involved until this point, it’s possible he just learned the facts of Leamas’ case and has shown up out of compassion. Or maybe the Circus didn’t leak the information about Leamas’ Switzerland meeting, and Smiley is trying to understand what really happened. Either way, at this point, readers are aware that something larger is going on behind the scenes, something that doesn’t quite fit with the plan as they and Leamas understand it.

In East Germany, Leamas meets with an Abteilung officer named Fiedler, who hates Mundt with a passion and has been assembling evidence against him for years. The few sparse clues Leamas delivered, combined with other things Fiedler already knew, are enough to arrest Mundt as a double agent – recruited by the Circus when he was in London and paid by Leamas through the deposits made in false names. Note that, by the time readers finally learn the details of Leamas’ plans, le Carré has introduced new sources of tension by having Leamas trapped behind enemy lines with some sort of other plan churning behind his back. He builds on this tension by having Mundt try to arrest Fiedler and Leamas. In the end, Fiedler rallies his forces within the Abteilung and puts Mundt on trial.

As Leamas’ second-level plans seem to move toward a successful conclusion, the tension between the second and third levels continues to ramp up. Someone in the Abteilung arranges for Liz to come to East Germany. Then, just as Fiedler presents a seemingly impregnable case against Mundt, Liz is brought in to testify on Mundt’s behalf. Leamas is horrified that she’s there, she is desperate to keep him from being hurt. But she has no choice but to tell how Leamas was not the broken man he seemed, and that the Circus came to help her after he disappeared. It exposes Leamas as a plant, he and Fiedler are arrested, and Mundt is completely exonerated. It could be the end of all tension, except . . .

Last month, I’d said that you can’t have your viewpoint characters know things your readers shouldn’t. At this point, le Carré pulls off one of the few exceptions to that general principal. Just as all his careful plans are collapsing around him, Leamas’ suddenly realizes what’s truly going on – he penetrates to the third layer. And le Carré ends the scene before readers discover what Leamas has realized. They really have no choice but to keep reading.

The truth becomes clear when Leamas is spirited out of prison in the middle of the night – by Mundt. As he and Liz drive toward Berlin to be smuggled back across the wall, he explains what he’s realized to her. Mundt genuinely is a double agent, working for the Circus. Fiedler was getting close to exposing him. So Smiley both sent Leamas to confirm Fiedler’s case – without telling him, because his ignorance made him a better witness – and set up Liz to follow and discredit him.

But even though all three layers of the truth are now fully exposed, le Carré has one more source of tension up his sleeve. As Leamas explains the real plan to Liz, he also reveals the thinking of the men behind it, who are willing to risk the lives of innocents like her and honest operatives like himself because they are fighting to prevent a war. Compared to the nuclear struggles between east and west, the lives of people like him and Liz don’t matter. Liz says that using good men and women like that is barbaric, and that he is just trying to convince himself that it’s necessary — he doesn’t really believe it. And it’s clear that she’s right. Note that it’s only when the third level is fully out in the open that we can also see a long-hidden, slowly-developed, character-driven source of tension. Leamas is having a crisis of conscience.

He and Liz reach the East German side of the Berlin Wall and are told what they need to do to climb over without being shot by the guards. But as Leamas goes over the wall, Liz, coming up the ladder behind him, is killed. He realizes then that the people he works for couldn’t let Liz live, given what she knows about Mundt, that she’s the latest innocent sacrificed for the cause. And his crisis of conscience resolves. He can no longer do his job and keep his humanity. So he climbs back down on the Eastern side of the wall and, literally in the last paragraph of the story, is shot as well.

This may be the most important lesson you can learn – that the best stories can break down the nice neat distinctions that writing teachers like myself often make. Last month, I’d said that if your story is more plot driven, you might want to withhold information until the end. If it was more character driven, you might want to reveal information early. Yet le Carré delivers a story in which he hides all the various layers of manipulation of information to ultimately set up a character-driven story. And through this masterful interweaving of plot and character, he manages to keep the tension high until literally the last paragraph.

How do you learn to do this yourself? Watching the movie probably isn’t enough, great though the cast may be. Read the book. Read it more than once – once you know the story, you can watch the mechanics of it unfold. Read le Carré’s other works, paying attention to how he moves fluidly between various levels of reality and balances plot and character driven tension. Steep yourself in the works of the master.

Then choose your next master and do the same.

Of course, I welcome any and all comments on le Carre — or your own preferred master of tension-filled plotting. As I say, I often learn as much from the comments as I put into the article. But I’d like to renew an offer I made a while ago. If you have any questions about your own writing, feel free to ask, either here or on the WU Facebook page. If the answers are of general interest, they may show up here. Watch this space.

Dave,

I’ve been re-working the first third of my novel into one POV instead of two. In the process I began to see how paying out information to the reader via the character’s flawed understanding of events gives a whole new level of tension to the story. Your previous post helped me with this a great deal, although the work has now become much harder (she says with a smile). I now have charts and graphs on my walls and have to take more walks, but I’m seeing results on the page.

My favorite novel by Daphne du Maurier is ‘the House on the Strand’. It involves time travel and has the protagonist balancing two lives instead of one, each life giving him pieces of information about the other. It’s full of surprises, enough so that I’ve already read it four times. So, once more for study purposes, and then Le Carre again. Thanks for an awesome post.

Hey, Susan,

One of the problems with telling your story from a single perspective — even more so if it’s a first-person perspective — is that your readers only get one view of the action. But if you’re aware of the other action going on behind the scenes, you can use that single viewpoint to create tension. It sounds like you’re mastering that.

And kudos for reading The House on the Strand four times. I really think that’s the key to understanding how plot works. When you know where it’s going, you can pay attention to how it gets there.

Dave-

This and your prior post are important ones. You are empowering authors. They have more control over their fiction, and their readers’ experience of it, than they realize.

Why do novelists nowadays sound so helpless, not only in facing publishing but in their writing process? Perhaps that reflects a general feeling of helplessness we have with respect to the world in the 21st Century. Maybe. But it doesn’t have to be that way.

What I would add to your excellent thinking is that le Carré’s double and triple game springs naturally out of his subject matter: Cold War spying. What of authors who are not working with stories in which deception is the point?

Any story can achieve greater power by withholding from the reader, it’s a matter of deciding to do so and setting about doing it. It takes some confidence. That in turn, I think, comes when authors have in hand the skills to bond their readers to their characters and worlds even when not everything is revealed.

Maybe the confidence to withhold from readers is a masterly skill that comes with experience, but I don’t think so. The Spy Who Came in From the Cold was le Carré’s first novel. If he was able to do it, why not everyone reading your post today?

Thank you, Don. And you’re right that this sort of multi-layered plotting is not only common but expected in spy thrillers. Most mysteries do manage two levels — what the detective knows and what actually happened — that come together in the end. And any story that involved intrigue, whether a historical novel (we’re watching the PBS Wolf Hall now) or fantasy (Game of Thrones), will have a story working on several levels of reality.

Some of the helplessness I’ve seen in writers stems from the sense that they either have to write intuitively — they have to write what feels right and follow their characters wherever they lead — or that they have to follow the advice we give here mechanically — following the steps to make their first five pages gripping or to put a certain amount of microtension in every scene. They wind up looking at their stories and either seeing lovable characters in a hot mess of a plot, or an intricate, delicate machine of a plot full of characters who are just cogs. And they feel helpless because their story just isn’t working, even though they’ve done everything right.

One reason I wanted to explore le Carre is that he masters the mechanics that we write about so often, then uses them to creates a human, heartfelt story full of living characters. His plot is a game of three-dimensional chess, but his characters are never just pieces on the board.

It’s not easy to get to this state of mind. You need to know the intricacies of how to manage tension or reveal information or plant clues or spring surprises — all the elements that make for a good plot. Then you have to let all those mechanics sink into the background as you write, allowing your subconscious to take care of them while you follow the lives of your characters.

The metaphor I keep coming back to is muscle memory, something familiar to musicians. When I’m playing a baroque chorale prelude on the pipe organ, I’m not thinking about how exactly I’m going to pass a phrase smoothly from one hand to another or how I’m going to shift from heel to toe to play a passage on the pedals. I’m thinking about how the musical attention flows from the countermelody to the cantus firmus and back, how the harmonics develop to the big payoff at the end of the line. I’m focused on how the music feels because I can trust that my hands and feet, trained by long practice, can take care of the mechanics without me.

In the same way, you essentially have to learn the mechanics — the best way I’ve found is by reading books several times, so you can pay attention to how the plot works once you know where it’s going. Then forget about them, and write from the heart.

Dave-

[le Carre plays] a game of three-dimensional chess, but his characters are never just pieces on the board.

…learn the mechanics … then forget about them, and write from the heart.

Great wisdom there, Dave, and a deep understanding of the dichotomy that authors face and how it trips them up. Neither characters nor plot by themselves will lead one to write great fiction. One must embrace both.

Dave,

Thanks for powerful insights and useful advice. Also for the summary of LeCarre’s book, which I read as a young adult (perhaps as a Reader’s Digest condensed version?) and now must pick up again to read with greater appreciation.

Inaccurate perceptions, manipulation, betrayal, mixed loyalties, fatal mistakes based on misinformation–these aren’t limited to spies and thrillers. They’re the stuff of everyday life. As an employee of a large hospital, I see these things daily. Now you’re helping me use these in my WIP, and I’m grateful!

What a delicious opportunity to write stories in such a way that we peel back the layers of reality for our readers, using the tools of intelligent design to delight and grip the reader as we reveal the character of the soul–which LeCarre appears to have done well.

Watching “The Imitation Game,” which features a man who’s unable to interpret a world of duplicity, hidden social cues, and manipulation, I’m grateful for the intelligence gifted to most of us to probe and make sense of a world often confusing, threatening, and sometimes terrifying–but always fascinating.

Thanks for more tools to do that as a writer. This has been a very helpful post.

Dave, your post was incredibly illuminating for me and using John le Carré,’s The Spy Who Came in From the Cold (one of my favorite authors and books) really helped me grasp what you meant by the process of creating layered tension. John le Carré,’really is a master and the way he layers in each level of tension is like watching the process of weaving in that the threads (plot and character) twine together so beautifully and with such apparent ease but the result is something quite complex and amazing.

It’s yet another reminder for me to continue to delve deeper and deeper into the craft of writing whilst enjoying capturing the stories that play out in my head. The writing is organic for me, learning writing craft more technical but, twined together with time and practice, the ‘how’ to engage the reader and when and who should reveal information is (I hope) becoming a more natural inclusion in storytelling. I feel like the more you blend craft capability with your natural storytelling the better the end result because it doesn’t feel like you are trying to force two competing elements together, but rather they are interdependent concepts that cross over at natural points along the way to produce smoother writing.

Looking at it from the reader’s perspective I certainly find it a much more enjoyable experience if the tension and mystery/intrigue is sustained and, in fact, continues to build right up until the end of the story.

I think it’s time to go find my favorite le Carré books again.

Thank you, Ellie. And see my response to Don’s comment. One of the reasons I enjoyed the le Carre book so much was that he hits a beautiful balance between a technically brilliant plot and engaging, organic characters. These two are often treated as if they’re distinct — a writer can do either one or the other well, and aspiring writers should focus on their own strong suit. But the best writers do both.

Have you read The Girl on the Train, Dave? It’s been #1 on the Kindle lists for months now, and in good part I think it’s because Paula Hawkins has mastered some of the techniques you’re describing. She withholds key information by altering POV at critical times, makes the protagonist an unreliable narrator, and then gives enough information to imply that said false version of reality will have fatal consequences if the MC doesn’t sharpen up. The external plot is strong, but ultimately it’s a character-driven redemption plot which is the most satisfying aspect of the story for me.

Hmmm. It’s been years since I read le Carré’, but to borrow Shawn Coyne’s terminology, it would be a spy thriller with a disillusionment plot, right? So tension can shift handily from satisfying the requirements of both genres, much as with TGotT.

I haven’t read it, no, but I’ll look for it. Most of my pleasure reading tends to be a bit older, but I do need to keep a lookout for writers who are still doing it well, if only for the sake of encouragement.

And I’m not so sure about the disillusionment plot. I think disillusionment is when you give up on your ideals. Leamas becomes disillusioned with his job, certainly, but I think he embraces his ideals in the end.

Two years ago, I wrote a piece on how and when you could get away with killing your main character. I think le Carre pulls it off nicely.

https://staging-writerunboxed.kinsta.cloud/2013/04/08/writers-who-murder2/

Hi, Dave:

I’m reminded of the thing that Donald Rumsfeld said when the Iraq War was going sideways: There are known knowns and known unknowns, as well as unknown knowns and unknown unknowns — i.e., things we know we know, and things we know we don’t know, as well as things we don’t realize we know, and things we don’t realize we don’t know. I thought that was kind of masterful, and I wasn’t inclined to like the guy, but he caught a world of crap over this insight, which was likened to Bill Clinton’s “It depends on what your definition of ‘is’ is.” (Which, in the context of the question he was asked in his deposition, was a perfectly reasonable — if snarky — response.)

The levels of knowledge the POV character possesses can track a similar logic, though that can get unwieldy. I think the reason le Carre succeeds so masterfully is that he doesn’t get lost in that matrix, but instead roots the problem in what the various characters know — and more importantly, act on.

What particularly impressed me in your example was how le Carre mastered his reveals through action, instead of exposition. The separate level of reality is revealed through the occurrence of something unexpected, which the POV character’s understanding can’t explain. This provides that gratifying shock that readers love and that Lance Schaubert described so well in his recent WU post, “Fallacy: The Primer for Surprise.”

I also believe in the old saw that trying to determine which is more important, character or plot, is like asking which side of the dollar bill is more valuable. Henry James said: “What is character but the determination of incident? What is incident but the elucidation of character?” The two are inextricably linked. Plot is nothing but the unfolding of the main characters’ pursuit of their desires in the face of overwhelming conflict.

This is where I find so many of my students and clients going wrong: They feel a need to provide information, rather than make the provision of information an element of the characters’ drive to fulfill their ambitions in the face of intense opposition.

I’m going through this now with the next novel: Trying to understand how the characters’ behavior dictates when reveals can be delayed to greatest effect, not making the characters my plot puppets and engineering their behavior to justify my spoon-feeding the reader information at the times I want to reveal it. It takes a lot of time, patience, and thought to make that work.

BTW: One of the most rewarding compliments I ever got in a review was a (favorable) comparison of my third novel, BLOOD OF PARADISE, to A CONSTANT GARDENER.

Great post, as always, Dave.

The Spy Who Came in From the Cold was Le Carre’s third novel, not his first.