Learning to Love your Fanatic

By Dave King | February 17, 2015 |

“The robber baron’s cruelty may sometimes sleep, his cupidity may at some point be satiated; but those who torment us for our own good will torment us without end for they do so with the approval of their own conscience.” C. S. Lewis.

Fanatics make terrific villains, whether it’s an animal activist destroying labs where lifesaving drugs are developed, the mother who ruins her children’s lives in order to save their souls, or a terrorist blowing up civilians to trigger the holy war. Because fanatics are obsessed with a single idea, they’re impossible to reason with. They’ll cling to their idea regardless of evidence or argument. They’re often blind to the damage they cause as well, continuing to destroy the lives around them with impunity because, as Lewis says, their hearts are pure.

Yet this sincerity makes them easy to humanize. Psychopaths, by contrast, don’t feel that the people they hurt are really people, which makes them less than human themselves. It can be frightening to watch a character fall into the hands of a serial killer, say, but in some ways it’s no more emotionally engaging than if the character is attacked by a wolf.

Fanatics, though, are generally working for what they see as the greater good. And the ends they’re fighting for aren’t necessarily bad things. Animal testing is often cruel. Everyone wants the best for their children. And as John LeCarre proved in The Little Drummer Girl, readers can even be brought to understand a terrorist’s aims.

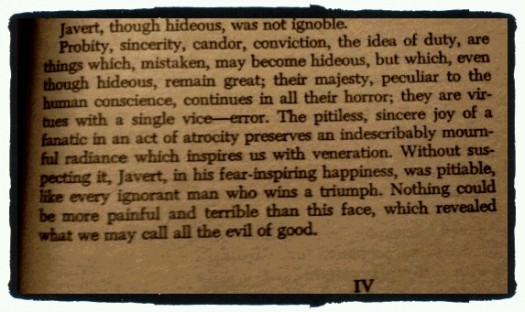

Giving your readers a sympathetic heavy draws them more firmly into your story. Both sides of your conflict become human. And while readers may still want your main character to win, they’ll feel pity for your villain, giving the conflict a new emotional level. Javert, who dogs Jean Valjean out of a fanatical devotion to the rule of law, is in the end more tragic than evil. Readers feel sorry for him when he throws himself into the Seine.

But Fanatics are easy to get wrong. I recently had a client whose antagonist venerates a guru who was trying to return her followers to a simpler life. He is so adamant that machines are destroying people’s lives that he plans to sabotage some equipment keeping critically ill people alive. But he persists in his plans even when his guru tries to stop him. This inconsistency in his character keeps him from becoming real. I still can’t imagine myself into his state of mind.

The best way around this problem, and the one I suggested to my client, is to learn to love your fanatic. Your readers will never be able to put themselves into your fanatic’s head unless you can go there yourself. Not that this is easy — it means sympathizing with someone you violently disagree with.

The best approach is to focus on the good things the fanatic is trying to achieve. You need to make your readers see the shining beauty of whatever idea drives them or the collapse of all that is good and holy that they’re fighting to avoid.

Ellis Peters’ Brother Cadfael mystery, The Heretic’s Apprentice, involves a young man being tried for heresy by a Canon Gerbert, a travelling inquisitor. Cadfael and the other monks at the monastery like the young heretic and see Gerbert as close-minded and self-righteous. But mid-trial, Cadfael has a sudden vision into Gerbert’s world.

For the man really had, somewhere in Europe, glimpsed yawning chaos and been afraid, seen the subtleties of the devil working through the mouths of men, and the fragmentation of Christendom in the eruption of loud-voiced prophets, bursting out of limbo like bubbles in the scum of a boiling pot . . . There was nothing false in the horror with which Gerbert looked upon the threat of heresy.

And from that point on, Gerbert is a human being, to Cadfael and to readers.

So who’s your favorite fictional fanatic? Why does he or she work? Have you known any fanatics who have fallen flat?

A timely reminder. It made me think that, as things get worse for the villain as she ups her game to get what she wants, it is also a good time to remind readers that her aims are to make the world a better place (her way), and that she believes the ends justify the means.

A little humanity goes a long way. I have one of those scenes coming up – let’s see what I can do.

Alicia

Hey, Alicia. Sounds like this caught you at just the right time. And if you run into questions while working on the scene, you’ve got a lot of people interested in the subject following the discussion here. So ask away.

Dave–you pose a useful matchup: the psychopath versus the fanatic. I certainly agree with you when you compare the hapless victim of a psycho to someone attacked by a wild animal. The reader can’t identify with a de-humanized nut case. All the reader feels is a sense of outrage and shared fear with the victim.

As for fanatics, they can be different, but I think of them as variants of the psycho. They are means-justify-ends characters, and as such, like the psychopath, they can conveniently reduce those in their path to objects. The serial killer’s victims are prizes or challenges, the fanatic’s victims are “collateral damage” on the way to what you call the greater good. The usual way to make them interesting is make them cunning (the nut), or intellectually sophisticated (the fanatic).

Barry, I absolutely agree that fanatics can be every bit as dangerous as psychotics, especially if you’re in their way. That’s one of the things that makes them so hard for writers to love. You’ve got to have a lot of compassion yourself to see the good in someone even as you hate the mayhem they’re causing.

Excellent advice, Dave. In my workshops I stress that evil characters don’t wake up in the morning thinking “What fresh evil can I do today?”(except that guy played by Mike Myers). They think they are justified. So I counsel writing out a closing argument for the villain. He is standing in front of a jury and has to convince them his actions in the book were right.

For a chilling, real world example of this, see Hermann Goering’s testimony at Nuremberg.

Jim, that is a GREAT exercise! Thank you for everything.

I agree with Vijaya, James. That’s an excellent exercise. Thanks.

I actually HAVE such a court case coming up in Book 3: the parties present their case to the judge in a high-stakes custody battle.

And I have been very careful to get to that point in plotting with plenty of ammunition of both sides. And the results matter.

The rough draft has been a lot of fun to write, and no making it easy for the winners – the cost could be exhorbitant. Pyrrhic battles, anyone?

Great advice. I tend to write domestic stories so the antagonists aren’t pure evil … they could be you or me, misguided, full of good intentions, doing bad things. And doesn’t the devil cloak itself in sweetness and doubt? That’s all you need sometimes to shatter your convictions.

Hatter’s Castle by AJ Cronin portrays the arrogance of a man and how it affects each member of his family. A very domestic tale, brilliantly told. From the 1930s.

For the more Hollywood type of villain, I’ve enjoyed Michael Crichton’s villains in Micro or Timeline. But they aren’t as flesh-as-blood.

I had to put down a book this week because the protagonist was falling flat for me. Rather than threatening, he seemed almost silly, his arc predictable and sterile. I flipped ahead and saw just what I expected, a guy who goes from bad to good, but for no believable reason. The time we spent inside his head seemed to only scratch the surface of what I hoped would be a complicated and tormented person. When it didn’t happen by pg 100, I got annoyed and gave up reading.

I love the idea of the protagonist finding a mirror in her antagonist. Sherlock Holmes finds Moriarty a challenging opponent because of his brilliance, warped though it may be. It makes me want to know what happened to M to make him turn out that way. One of my favorite all-time nasty boys is Gollum/Smeagol, who wears it on his sleeve. I, as a reader, saw sides of myself in that duality, and when I learned about his backstory, I felt for him. His obsession kills him in the end, but he lives on for me as one of the most memorable.

Susan, I wish I’d thought of Smeagol as an example. Tolkien does to a wonderful job of humanizing (hobbitizing?) him. And in so doing shows the effect the One Ring can have on an otherwise good character.

And are you familiar with Elementary, the American show that moves Sherlock into the modern world? [SPOILER ALERT] In it, Sherlock was still very much in love with Irene Adler, who died before the series began. But it’s eventually revealed that Irene was actually herself Moriarty. She pretended to fall in love with Sherlock, then faked her own death to drive him into drug addiction and keep him from spoiling her plans. Thing is, she genuinely fell in love with him, and he her, because each had finally found someone as brilliant as themselves.

That sounds so juicy. I will check it out. Thanks, Dave.

The biblical and iconic Queen Jezebel plays a role in my story. I’ve thought about what her motivations may have been, to turn Israelites to the worship of her god. She comes as a treaty-wife, a pawn. But she was a high priestess of Baal, a princess of Tyre. She was her father’s right hand. Then she was sent away, and her brother was destined to rule–in her place. Her new husband, King Ahab, is enamored of her, is weak in many ways, but he is the ruler. I see her as longing to prove her worth (to her father as well as herself) and establish her own power–so that no man can ever again set her aside for another.

That sounds like a wonderful way to humanize a character who is a classic villain.

It also brings up another interesting point — the effect of culture on creating fanatics. I know a lot of people who cause mayhem and fight to overturn society, from Spartacus to Wat Tyler to Palestinian suicide bombers, resort to violence because they have no other way of relieving the misery of their lives. Jezebel is a good example of this.

Something that occurred to me after I posted the article: I draw a contrast between psychopaths, who don’t care about people, and fanatics, who care too much. But there are a lot of attempts, mostly on television, to humanize psychopaths, and the closely-related sociopaths. To effectively use emotionally stunted characters as the good guys. Dexter’s the clearest example, but Benedict Cumberbatch plays Sherlock Holmes as a “high-functioning sociopath.” And Sarah Shahi does a good job with the sociopathic Sameen Shaw on Person of Interest. (On being asked how she deals with stress, Shaw said, “Well, every once in a while, I shoot someone.”)

So how well do you think this works? Can readers really be made to care about a character with little emotional connection with the world? Or is this just a gimmick making its way through the collective culture? I wonder, because I can’t think of any historical examples of this sort of thing.

The killer in The Architect by Keith Ablow is a notable villain whose fanaticism is founded in aesthetics. Bad taste should be eradicated.

Who can argue?

Okay seriously, we all know that justifying the villain is the surest way to a scary villain. Your advice and Jim’s exercise are variants of stuff we’ve heard many times. So why do we keep getting cardboard baddies, even in print?

The reason, I think, is that we are afraid to face our own inner fanatics. We all are capable of great evil in the name of good–history and science have proven that–and that scares us.

But I think there’s an even deeper reason: guilt. We’ve all done wrong, been unjust, or just careless. We’ve neglected the needy and justified it. We’ve hurt people. We’ve clung to our personal beliefs when they clearly were wrong. We suspect we could kill.

And in fact some of us have. And all of us have held the cloaks. (No? Consider, do you pay taxes? If you have you’ve paid to have people killed.)

How the hell do we live with ourselves? We’re good at denial, I guess, and have erected elaborate mental constructs to make our guilt go away.

But those constructs are shaken when we open our minds to the justified evil in others. It makes us face the justified evil in us, and that is not a comfortable thing to do. Better to make our baddies pure bad.

Then they’re not like us.

I think you’re absolutely right, Don. When we make our villains less than human, we have the chance to project our own darkness onto them.

Ironically, that’s often what’s going on when fanatics justify the damage they do — the people they’re attacking deserve it because they’re so bad. So the best way to understand fanatics is to not be one yourself.

Dave, I immediately thought of Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment who is frantic with his theorizations of the “extraordinary” person contrasted with the “ordinary” person. Dubbing himself one of the extras, he kills the pawnbroker to show that he’s above any moral code (but in the process, kills her sister as well). But he descends into full madness when his fanaticism and his obsessions overwhelm him.

But because we are in his fevered head for much of the book, and are privy to his remarkable (and deeply wrought) rationalizations, it’s hard not to feel some sympathy for him, murderer that he is.

Another excellent example, Tom. Thank you.

Hi, Dave:

I’m on a panel that focuses on the villain at next month’s Left Coast Crime in Portland, and will be sharing the stage with Chelsea Cain, Laurie King, and Sean Chercover — three very smart writers who know this terrain well.

Your quote from Lewis resonated because those are the kinds of quotes I’ve been collecting and thinking about.

Graham Greene’s justification of Harry Lime’s dilution of penicillin to sell on the black market in post-war Vienna (THE THIRD MAN) is one of my favorites:

“Like the fella (Nietzsche) says, in Italy for 30 years under the Borgias they had warfare, terror, murder, and bloodshed, but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and the Renaissance. In Switzerland they had brotherly love – they had 500 years of democracy and peace, and what did that produce? The cuckoo clock.”

Then there’s Noah Cross’s justification for driving farmers off their land though drought to create the San Fernando Valley (CHINATOWN). When Jake Gittes asks what can he buy he doesn’t already have, Cross replies: “The future, Mr. Gitts! The future!”

But the most chilling may be the Joker’s in THE DARK KNIGHT, when he tells Batman that they share a common belief in fairness. “And chaos is fair.”

I concur with Jim, and advise students that they must “justify, not judge” their opponents (villains). And I also agree with Don’s assessment that we still see so many bad villains because writers are afraid to address the villainy they take part in every day.

I’d take it a step further. Like you say, we need to remember that villains, like heroes, are fighting to create, preserve or defend a way of life they believe in — even if that way of life is a creative chaos (the Joker and Harry Lime), or a world where the powerful, in order to create great things, must turn a blind eye to some of the human cost (Noah Cross).

It’s this latter justification that I find particularly compelling, because it lies at the heart of all civilization — that there are those, due to their ambition and vision and sophistication, who get to rise above the rules the rest of us must live by, because their greatness leads to a greatness we all share in — whether they are divine right monarchs or merely “job creators.”

We implicitly buy in to this justification every day; it’s the Randian heart of current-day capitalism. And I think many writers, especially those who see financial success as a positive goal, don’t want to see (and more importantly feel) how commonly held that conviction is, how large a part it plays in each of our lives on a daily basis, and how easily — and often — it paves the highway to cruelty and suffering.

The fanatic, though, seems to see himself more as a servant of a cause than its figurehead. And to make a fanatic work that need to serve must rise above a mere servant’s will. That will must be as big as the cause the fanatic uses to justify his actions. It must be as relentless as that of a Noah Cross or Harry Lime or Joker. Otherwise the crimes, no matter how reprehensible, will seem somewhat small.

Great post. I totally intend to borrow you insights for my panel. (I’ll credit you, don’t worry, and WU in general. Where else do we get to throw ideas like this around?)

Fascinating stuff, David. When I wrote this thread, I didn’t realize it would trigger so much speculation.

Feel free to use anything you find here.