Anything for the Story: Tension

By Guest | January 4, 2014 |

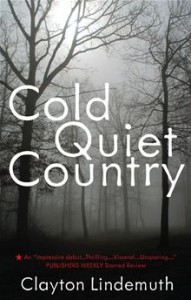

Today’s guest is Clayton Lindemuth, with a post about tension and author integrity because first, they are linked, and second, learning to let go of our nice selves is critical to good writing. If the reader doesn’t perceive the reality of the challenge or conflict facing the protagonist, the story is weak. His debut, Cold Quiet Country, set in winter of 1971, is a is a go-for-the-jugular country noir… “Lindemuth carefully weaves characters’ backstories into this thrilling narrative, and his visceral prose and unsparing tone are wonderfully reminiscent of such modern rural noir masters as Tom Franklin and Donald Ray Pollock,” from Publishers Weekly starred review.

Clayton lives in Chesterfield, Missouri, with his wife and dog. You can connect with him on Twitter and Facebook and for more information visit his blog and website.

Anything for the Story: Tension

How do you make your reader bite her nails so hard she doesn’t know what she’s doing until two knuckles are gone? Let’s frame the question.

Our impulse as writers is to think of something interesting, tell the reader, hey, check out this interesting situation—a boy feels this way; a girl feels that way—and then wonder why our beta readers tremble in the corner and won’t make eye contact.

The reason “show, don’t tell” is the First Rule of Fiction is that showing accomplishes something telling doesn’t: no matter how precisely we draw a picture, we are still forcing our reader to interpret it. “Show don’t tell” creates reader engagement; it compels her to think, to ponder, to test hypotheses.

So what does an engaged reader asking questions have to do with tension? Bear with me just a little longer, and let’s expand focus.

Sometimes we find ourselves writing dinner table scenes because they’re comfortable. However, if there isn’t a bomb under the table, or a pistol in Mom’s bra holster, or at least Mom daydreaming about her Sicilian lover—something with latent tension—we’re probably boring the reader.

Lob a Bomb

The first step in creating tension is to avoid writing about things that are dull. It’s like Stephen King’s advice to remove everything that isn’t Story, or Michelangelo removing everything that isn’t David. In the human experience, about forty zillion things are heart breakingly rotten. Find one of them, light the fuse, and pitch it under your protagonist’s dining room table.

Place your character into situations that carry an implied threat. The threat doesn’t have to involve physical harm. It could be emotional, financial, spiritual, or involve a hundred other dimensions.

Place your character into situations that carry an implied threat. The threat doesn’t have to involve physical harm. It could be emotional, financial, spiritual, or involve a hundred other dimensions.

Don’t Defuse the Bomb

Next consideration: nothing destroys tension faster than defusing a bomb right before you throw it.

This hearkens back to why we “show, don’t tell”: we want the reader to keep putting herself into the scene, comparing the bad guy to Uncle Eddie, and most importantly, asking questions. However, as soon as the bomb is defused, the most important question—is this whole family going to blow up while they’re eating ham and gravy—is answered.

Writing Cold Quiet Country, I knew from page one the struggles that would befall Gwen, the red-headed, forced-to-grow-up-too-soon young woman whose disappearance forms the backbone of the narrative. But I withheld that information from the reader until I conveyed enough context to ensure the unraveling has maximum emotional impact.

In your story, after you’ve chosen a situation with latent tension, brainstorm ways to ratchet it higher. What’s the worst thing that could happen, right now?

Make it happen.

You Have to Be the Villain

I know it’s tough. We want to be nice people and hint to the reader that everything turns out okay. After all, we’re not bad, bless our hearts, we’re just telling a story. We wouldn’t even be thinking about evil stuff if it wasn’t for our duty as storytellers.

However, good storytelling requires you to keep your reader uncertain of the fates of the characters she cares about. In fact, the more committed you are to conveying anything of significance, the more willing you have to be to honestly present the evil character, and make him utterly convincing.

Our jobs are critical. We’re not enablers for voyeurs. We stun our readers into a higher understanding of the lives they affect. Our charge is to change the world by enlightening it, hence we create fictions that fracture emotions and force our audience to contemplate with feeling issues they would otherwise only contemplate with intellect, or not at all.

In my life there really was a Sheriff Bittersmith, the arch evil narrator in Cold Quiet Country. He molested girls and knocked their lives’ trajectories into paths that included unspeakable pain. He died of old age after forty years of un-confronted pedophilia and rape.

I didn’t want to write Sheriff Bittersmith in first person. To me he’s the Jeffrey Dahmer of bad guys. But the truth is that the reader must believe the author is comfortable enough in the bad guy’s skin to let him do his damage. She has to know in her soul that you have the guts to destroy the character you love, to break her heart, her bones. Sheriff Bittersmith commits acts that made me drip tears into the keyboard—but you can be sure no reader will ever turn the last page without feeling something. That’s why I wrote him honestly.

Putting it All Together

The foundation of every great story is a situation with latent tension. Our job is to find it, then protect it, augment it, exacerbate and prolong it.

Your story doesn’t have to be about a heinous act for the principle to stand. Consider this: your protagonist is a cheating spouse. The reader automatically needs to know if she feels guilt, or is the marriage over? Does the husband know? Suspect? Or is he in the TV room with a beer and the game, oblivious?

You can err and defuse the natural tension quickly: the divorce papers are on the kitchen island and her soon-to-be ex-husband is scribbling his signature.

Or you can enhance the natural tension. She’s terrified of both her Sicilian lover and her husband, but even though she tried to break it off, her lover won’t let go. Her husband is suspicious, and he’s standing in the bedroom entrance with her cell phone, looking quizzically at the screen, saying, “Who’s Giovanni, and why has he called ten times in the last two days?”

Bottom line: out of the forty zillion things in the human experience that are simply wretched, you have to get cozy with one, and you have to tell it honestly. Lob one of those disasters onto your protagonist’s breakfast plate, and pay special attention to encourage the instinctive fear your reader will feel.

You don’t get to be the good guy or gal. You’re the author. If you need to roll a deck of Marlboros in your t-shirt to get in the mood to be a badass, well, anything for the story.

I’d love to see in your comments the first inherently tense situation that pops into your mind. Let’s start cataloguing the forty zillion…

Hi, Clayton. Thanks for the strong reminders about making tension. In this article, you wrote about your tears in creating Bittersmith in COLD QUIET COUNTRY. Robert Frost said, “No tears in the writer, no tears in the reader.” In his Paris Review (1960) interview, he offers more on that:

“I’ve often been quoted: ‘No tears in the writer, no tears in the reader. No surprise for the writer, no surprise for the reader.’ But another distinction I made is: however sad, no grievance, grief without grievance. How could I, how could anyone have a good time with what cost me too much agony, how could they? What do I want to communicate but what a hell of a good time I had writing it? The whole thing is performance and prowess and feats of association. Why don’t critics talk about those things—what a feat it was to turn that that way, and what a feat it was to remember that, to be reminded of that by this?”

https://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/4678/the-art-of-poetry-no-2-robert-frost

We all share some of those 40 zillion heart breakingly rotten things in the human experience that you mention, but the difference with us writers is the ability to turn the memories “that way,” to remind readers of their own feelings and let them share our characters’ lives by showing the rottenness “this way.”

Speaking of rottenness, ou have another great article in you, one about writing from the bad guy’s point of view. I’m on my way to the store for that pack of Marlboro in the meantime.

Thanks,

Audra

Audra,

I hadn’t been aware of the extended play version of the quote; it’s very interesting. And funny. When I was in college reading stale, dead texts, I had almost no idea that a human being was on the other side. Now after some of my simplicity has been beaten out of me, I can’t help but wonder at the lives of great authors apart from their writing. Great comment. Thanks,

Clayton

I just finished reading “20 Master Plots” by Ronald D. Tobias and it helped me kick my plot into “tension mode”. So happy for it, and am thrilled to get to writing!

Great post with winning reminders.

Alex,

You know I’m going to have to check that out. I never paid any mind to plot until recently… I just made a good guy and a bad guy and focused on escalating tension. The problem with my process was that it took nineteen full edits to make the story work… With my WIP I took my agent’s advice about plotting and all of a sudden, after two drafts I feel ready for a coat of polish. Thanks much for your comment!

Clayton

First inherently tense situation that pops into my head? A few years ago, someone told me something about writing horror and it was ‘just think about the worst thing that could happen’ (and I’m not sure if that’s good advice or bad) but I came up with having two choose between the life of two people, which one stays and which one goes.

Really great post, made me think. Thanks for sharing!

Anastasia, I’d say that’s a good starting place, thinking of the worst that could happen. If it’s organic to the story, meaning, not contrived, it’ll be believable. One thing I picked up by reading Lisa Cron (if you haven’t read Wired for Story, check it out) is that the conflicts you choose should be relevant to either the internal or external struggle your protagonist faces, otherwise it looks like a string of unassociated disasters. If each disaster pertains to a real struggle the character is dealing with, reader empathy and involvement will increase.

Thanks much for your comment! Choosing between the lives of two people has to be one of the oldest and most challenging of the forty zillion.

Clayton

I had to laugh, Clayton. I had a dinner scene in my WIP where I was trying to show the dynamics of this family, but when I read it over with a critical eye, I realized there was no tension, so I cut it. Tension and conflict are what propel a story forward and these must be shown, not told. And as you remind us, letting the air out of the balloon too early will drive the reader away. Thanks for a great post and best wishes for success with your new novel.

CG,

I learned that from Katherine Howell, an Australian author who did her masters work on tension. She told me that in an early version of one of her novels, a baby is kidnapped. The way she framed the story, though, the reader instantly knew from the kidnapper’s POV that the baby was fine, and the kidnapped filled with remorse. Which takes one of the most horrifying things a reader could worry about and reduces it to nothing. It was great advice, and I think timeless!

Thanks for a great comment!

Clayton

Great post about tension and thank you for that, especially today. I’m in the middle of revisions and I want to keep the tension going with regard to why the main character’s husband is so evasive and non-communicative. He has a secret and I don’t want the reader to “guess” what it is until the end. It’s difficult. Your “show, don’t tell” is what my editor keeps telling me. I’m trying!

Patti

Patricia, I’d look for situation in your story that you can tease out into an organic red herring. Then dive deep into your protag’s POV so you only see what she sees. Meanwhile, lay clues for the truth, so when the reveal happens, we all slap our foreheads and smile. That’s in essence what my agent said to me a couple months ago when I faced the same problem in my WIP.

Thanks much for your comment!

Clayton

I’ve quit my job three times. But we’ve never been able to find a replacement who lasts, so I keep going back. It’s been three years. Now there’s a situation fraught with tension!

Lori,

OH YEAH! I can see multiple directions that tension could blow up. You and hubby, you and replacement, even the dog has to feel the tension! That’s a perfect situation to start thinking about a character with a couple of problems… Nice. Thanks for posting!

Clayton

You not only understand the material about which you wrote today, you know how to write a blog post. No messing about. The post itself was compelling – and that’s a tribute to your skills as a writer. You understand how to convey a message without a lot of “slobber” – or, as Mr. King said, nothing that isn’t the “story”.

I think blog posts should be as well-honed as our manuscripts.

You are the kind of serious writer I like to read. Someone who gets this craft and understands how to deliver it.

I will now be checking out your book.

Well done on this post, man.

Best,

J.F.

JF,

You have to know how good that makes me feel. Ten thousand thanks to you!

Clayton

Clayton, what a great, timely post for me. I’m struggling with getting a novel idea to take off, and my great issues have been tension and conflict and making the main character active rather than passive. The inciting incident is MC’s sister’s suicide, an action clearly outside MC’s control. So I have to decide what tensions the sister’s death leaves behind (and there are plenty, including a three-year-old child). The internal conflicts are relatively easy; what’s hard for me is deciding how the MC *acts* going forward. This article helps; it’s one I’ll reread over the next few weeks to keep me focused. Thank you.

Gerry

I find myself referring back to advice from Lisa Cron’s Wired for Story… You have a great situation to drop a character into. I think the way to approach it is to know what your character’s internal and external motivators are, and then devise situations that challenge your protagonist. The deeper you go into the details of your characters, the more ideas you’ll get on situations that could arise organically that exacerbate everything bad. Thanks very much for your comment!

Clayton

You forced me to reexamine my writing. Like most writers I used to tell. I used to tell a lot. I realize now that telling allows for more emotional detachment in the writer and so, of course, in the reader. I realized that when showing I’d have chills descending my spine or I’d have to keep wiping my eyes to see the screen. Other times I’d allow something terrible to happen to the protagonist and remorse would flow over me, though I wouldn’t change what I wrote. The bombs are difficult to toss, but that’s when you know you’re doing it right. Thank you for this post.

Christina, you really nailed it. It’s easy to tell, and it allows us to dissociate from the ugliness, keep it at arm’s length. But showing drops us into the pain as much as it drops the reader. It’s uncomfortable. Well said on your part, thanks much for the great comment!

Clayton

Great post and I especially liked what you said about not diffusing the bomb, “I know it’s tough. We want to be nice people and hint to the reader that everything turns out okay. After all, we’re not bad, bless our hearts, we’re just telling a story. We wouldn’t even be thinking about evil stuff if it wasn’t for our duty as storytellers.”

I justify my evil thoughts every day. LOL

After reading this blog post, I understand a bit more about why you crafted the character of Bittersmith the way you did. As I said in the review I wrote for the book, I did not like him, and now I see you made him that way so I wouldn’t.

I had to laugh when I read your statement about dinner scenes. Too often they are just used for exposition. I remember taking a scriptwriting class once and the instructor said “don’t take your characters to dinner.” Of course, you can if you create a scene like that wonderful one in “When Harry Met Sally.” (smile)

Maryann,

Yeah, with Bittersmith I had a choice and I was very deliberate about making him true. Whether one believes there is no absolute right, no moral lawgiver or not, antagonists don’t benefit from their author’s moral relativism. That’ the most convoluted sentence I’ve written in a while… Meaning, we all know some things are rotten, and even if an author wants to shy away from the brutality that an honest representation an antagonist requires, the reader needs it. We’re hardwired with an understanding of evil because it’s real, and when we see bad guys who aren’t really bad because they grew up in a rotten neighborhood, part of us, as readers, feels cheated. Just my two cents….

Thanks much for your comment!

Clayton

Thanks for the great post, Clayton. I find that tense or emotionally-fraught scenes are the funnest to write. (And I’m a nice person!) ;)

Me too!

Clayton

Clayton, a thoughtful and well-written post, many sincere thanks. I write a mystery series, so my protagonist has her own issues that arch over the ‘puzzle’ in each book. I find that the more I know about her, the deeper jeopardy I’m allowing her to wallow in . . .

Marni,

Absolutely true! All those details open up tons of organic threads to develop. Thanks much for your comment!

Clayton, thanks for a really thought provoking post. Anyone familiar with Don Maass’s teachings knows tension is the lifeblood of any story, so I was very interested in what you had to say. I agree that if you have an evil character in your story, you need to make him utterly convincing. For me that means giving him both good and evil qualities. Even your human liver eating serial killer needs to be “likeable” in some way (Hannibal Lector is courteous to a fault). I would think likeability is especially important, if your story’s narrator is the evil character. I haven’t read Cold Quiet Country, so I can’t comment on Sheriff Bittersmith. But if you have made him totally evil, to the point of being totally unlikeable, how do you persuade your readers to stay in that person’s POV for an entire novel? Obviously, you did, so congratulations. But how did you do it?

Cal,

That’s a powerful question. First, I think we have to be careful to note that a sympathetic character isn’t necessarily likable. I saw a video of Tim McVeigh before he was executed and I felt bad for him… but I didn’t like him.

The real answer to your question, though, is I think this: readers get involved with characters when understand motivations, desires, and get to sit shotgun while the bad guy is doing what he’s doing.

I’ve read two dimensional bad guys, people who just do rotten things because the plot demands something rotten happen to the protagonist. No fun to read. But I’ve also read bad guys who are their own sick moral force in the story, and if the logic behind their actions is consistent, and the reader is privy to all of it, a sick kind of fascination sets in. I have another bad guy–my arch bad guy, the wickedest I’ve written–in Nothing Save the Bones Inside Her. I’m amazed at how often people tell me how mesmerizing he is.

The bottom line, I think, is not to make a bad guy likeable. Instead make his evil something that, no matter how horrifying, is just one bad decision away from any reader’s reality.

Thanks for the really good question!

Clayton

Tension and conflict are indeed the roots of a story, but I want to add that the tension doesn’t have to be earth-shattering. The “bomb under the table” can be something simple.

– John and Betty are fighting because Betty caught John in the arms of a clingy ex. John, who’s usually cold-hearted and proud, tries to apologize by making a romantic dinner for two. Just as he’s lighting the candles, the doorbell rings. It’s the ex.

– Betty meets John’s parents for the first time at a family dinner in their upscale mansion. It’s all going swimmingly. There’s just one problem: John and his parents believe she’s a brilliant lawyer. She’s actually a lawyer’s housekeeper.

– John and Betty try to spice up their marriage with a fun night on the town. But John forgot to make reservations at the restaurant. They impersonate a no-show couple to get in the door. Unfortunately for them, that couple stole from the mob. (This is the set-up of the comedy Date Night.)

The “bomb” can be a lie, a secret, pent-up resentments and frustrations, a third-party antagonist, etc. You can take your characters to dinner as long as the dinner is the backdrop, not the plot.

Tamara,

Those are some great examples…though I sure wouldn’t want to be John! Great comment, thanks much,

Clayton

Great info! I particularly like your reminder that the disaster and its resolution needs to relate to what the character is struggling with internally. He/she has to change, somehow, after the dust settles, after the she admits she’s cheating, after he admits he shot the dog. We have to be able to answer the “so what” question readers will be asking, and sometimes that’s the hard part, the part that makes you shake a Marlboro from the pack rolled up in your sleeve. Great post, Clayton! Much success with Cold Quiet Country.

Sophia / She Likes It Irish

Sophia,

Absolutely a great point to drill down on. I think that sometimes ‘artists’ create work that is brutal, but irrelevant, as if recording ugliness, and saying that it’s there, deal with it, is a work of art. See how faithfully I rendered evil? But the real artist is one who can make relevance, tie it to a moral, and make it all instructive without beating someone over the head with it. Your comment feeds directly into that–the internal struggle is often about right and wrong, and it’s where we have the most power as authors. It’s amazing how often we forget out most powerful tools. Thanks for a great comment.

Clayton

Clayton, this post has been so helpful to me. I decided to start my story over this year, and I’m looking for ways to increase tension.

Thanks so much for sharing! I hope you have a great 2014!

Jackie,

I tried to respond to you with a link but I think the spam catcher thought I was a bad guy…

I wrote something called Readers Want White Knuckles. If you google it with my name you’ll find it. It’s an article with a lot of tension techniques I found by studying some bestsellers.’

Just remember that if you use techniques, try to keep them organic to the story so the conflict/tension is relevant….

Thank you for commenting!

Clayton

Thanks Clayton. I’ll check it out now.

You don’t have family in Wilmore, KY do you?

A mother is trapped in car. The seat belt is stuck. The car is in the lake. The water is freezing. It’s the middle of winter. Oh yeah, don’t forget about the screaming baby strapped in the car seat in the back facing away from the mother. The cold water licking at her cheeks.

Brian,

That’s a great setup, and as soon as you add the details that make the people real, it’ll be a grabber. Nice. Thanks for posting!

Clayton

Realism for my characters is tough for me. I can picture them in my head and what they are doing, but putting in words on paper is most difficult.

I like your last comment about the fact that I don’t have to be good or bad–just the author.

I haven’t been making my “bad” characters as dominant as they probably should be, but I think I’ll try that with my next novel.

Connie,

Thanks for the comment. What I do when feeling that way is just start tying. Don’t be afraid to write words that are probably going to be cut. Sometimes a rolling start will give you a great insight or idea, a great conflict. Then just cut the garbage and tease out the gem!

Clayton

Clayton-

Nice to see you here. I once had my arm twisted behind my back by a bully and your post is kind of like that–in a good way. Tension. Yeah.

One of my workshop questions is, “What would make this problem worse?” (And worse. And worse.) I’ll now add to that your directive: Use it now.

Now, I would make the lover Swedish instead of Sicilian, but hey, I’m a guy and I quibble.

Nice to have a big dose of “show” on a Saturday. Thanks. And congrats on the success of Cold Quiet Country. Our chests are puffed up over at DMLA. We’re proud of you, and now I know why.

Donald,

It’s quite a thrill to respond to you. I got a lot of my worldview on writing from Writing the Breakout Novel, and working with Cameron is a delight. Talk about chest puffing, it’s a flat out honor to be represented by DMLA!

As far as CQC goes, it wouldn’t be in print without yall, and specifically Cameron’s tenacity–so thanks for much more than your kind words.

Clayton

[…] The post is about tension and bad guys in your fiction. It’s created a heckuva good showing for comments on a Saturday. Check it out here. […]

I found this post very helpful. The worst tension I can think of would be receiving a call from a hospital with a bad connection and having to hang up and have the person call back to find out what has happened; why the person is calling from a hospital.

[…] Lindermuth addresses story tension and keeping the reader uncertain; Kristen Lamb has tips to maximize conflict in your novel; and Victoria Grefer discusses how to […]