Writers’ Guides of the Past

By Sophie Masson | March 13, 2013 |

I’ve always been an inveterate collector of antique and vintage books, on all kinds of themes and subjects: fairy tales (amongst which a treasured 18th century edition of Madame Leprince de Beaumont’s tales, including my favourite, Beauty and the Beast); travel guidebooks (so useful when writing historical fiction); old crime novels; household hints and cookery; bound copies of old magazines, such as Charles Dickens’ Household Words—the edition which I’ve got includes the first, serialised appearance of Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White. I collect them ‘for fun and profit’, as the old saying has it: because I love old books and magazines, and the undiminished, vibrant life that comes so strongly off their yellowed pages: but also because they are so very useful to me in my work as a novelist. And now I’m collecting in an area very close to my heart–authorship–and it’s proving to be utterly fascinating: for not only do these old books provide an intriguing glimpse into the writing life ‘back in the day’, they also show quite clearly that despite all the many technological changes which have flowed into the everyday lives and methods of authors, in fact many, many things stay the same.

I’ve always been an inveterate collector of antique and vintage books, on all kinds of themes and subjects: fairy tales (amongst which a treasured 18th century edition of Madame Leprince de Beaumont’s tales, including my favourite, Beauty and the Beast); travel guidebooks (so useful when writing historical fiction); old crime novels; household hints and cookery; bound copies of old magazines, such as Charles Dickens’ Household Words—the edition which I’ve got includes the first, serialised appearance of Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White. I collect them ‘for fun and profit’, as the old saying has it: because I love old books and magazines, and the undiminished, vibrant life that comes so strongly off their yellowed pages: but also because they are so very useful to me in my work as a novelist. And now I’m collecting in an area very close to my heart–authorship–and it’s proving to be utterly fascinating: for not only do these old books provide an intriguing glimpse into the writing life ‘back in the day’, they also show quite clearly that despite all the many technological changes which have flowed into the everyday lives and methods of authors, in fact many, many things stay the same.

In the past, I’ve come across many passages in old books and magazines that deal with authorship and the publishing industry, such as Anna Dostoevsky’s fascinating description, in her posthumously published 1918 book Reminiscences (about her life with her famous writer husband, Feodor) of how the couple, wearied of low publishing returns, promises of promotion that never happened, and exorbitant discounts demanded by booksellers, decided that they’d do better self-publishing his latest novel, the huge, extraordinary, Demons, also known as The Possessed. Anna gives a blow by blow account of how they went about it, and reports on the huge success of the venture, both financially and exposure-wise (they put together a canny publicity campaign that was the equivalent of a ‘viral’ social media push today, causing a huge buzz about the book before it even hit the streets). So successful was it that lots of other authors, including a certain Tolstoy, rushed to ask them their advice on self-publishing! (Yep, nothing’s new under the sun.)

But passages like those, fascinating as they are, are only isolated pieces in books on bigger subjects. What I was looking for to start my collection of old authorship books were those that concentrated on that subject in its different variants. I’ve only started seriously collecting them very recently, but have already found some real gems.

Such as Andrew Lang’s jokily-serious advice guide to would-be authors, from 1890, How to Fail in Literature, which overturns the ‘Do as I say’ school in an entertaining manner. Here’s an example of a handy tip:

One good plan (for failure)is never to be yourself when you write, to put in nothing of your own temperament, manner, character—or to have none, which does just as well.

Here’s another:

A good way of making yourself a dead failure is to go about accusing successful people of plagiarising from books or articles of yours, which did not succeed, and perhaps, were never published at all.

And here’s a wry observation to give a sense of perspective, if you aspire to best-seller status:

..the laurels here are not in our thoughts, nor the enormous opulence(about a fourth of a fortunate barrister’s gains)which falls in the lap of a Dickens or a Trollope.

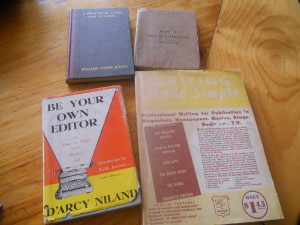

A Practical Guide for Authors, by William Stone Booth, published in 1907, is altogether a less fun affair. Subtitled ‘In their relations with Publishers and Printers‘, this book is not about the art and craft of writing, but sternly aims at giving authors the nitty-gritty of the business. And I mean the actual nitty-gritty! Here’s how it starts:

Write on one side of the copy…Use white paper, about eight inches wide..Do not use two sizes of paper in the manuscript. ..Number each sheet of a manuscript consecutively…

And so it goes on. Follows is a short chapter on how to offer a manuscript to a publisher, with advice that looks standard even today, such as:

Get a catalogue of his (the publisher’s) publications and satisfy yourself that his list is appropriate to the kind of book you have written.

And observations that sound a little odd to modern ears:

An author will sometimes wish to know the financial standing of a publisher and whether he manages his business on such a conservative basis that he will be able to pay his royalties for the full term of copyright.

(Yeah, sure, but good luck with trying to find that one out!)

Other chapter themes include agreements and contracts (much of which holds true even today), the British market, the American market, advertising, reviewing, proof-reading (including proof-reading signs), intensive chapters on British and American spellings and punctuation. Things which have changed completely (but may of course be in the process of reverting, as is the case with digital books) are attitudes to advances, with Booth wagging a finger at brazen authors who expect such a thing, and the position of the literary agent, with Booth sagely intoning, in a complete reversal of the modern situation that:

No publisher is likely to take quite the same interest in a book brought to him by an agent as in one that is brought to him directly by an author.

Another thing you’d rarely see in an authorship how-to book today is intensive advice on French and German spelling—many English-language books in those days reproduced entire phrases in those languages, untranslated—as readers were often expected to have a working knowledge of them from school.

Then there’s the books on the craft of writing, of which I’ve picked up two good examples from the 1950’s: Writing Made Simple (1956), a kind of early Writing for Dummies, written by Assistant Professor Irving Rosenthal of City College of NY, and Morton Yarmon of the New York Times. This book gives brisk advice not only on how to write all kinds of things—novels, short stories, articles, writing for TV, radio and movies, and ad copy—but also how to market your manuscript, constructing outlines, conducting interviews, finding reader interest (ie: knowing the market), knowing your libel laws, and lots more. Incidentally, the section on literary agents is much more encouraging than in Booth’s book of forty years before, with novelists being advised that a good agent is most likely necessary, while magazine writers may or may not find one necessary. And there’s a warning which holds true even today:

Under no circumstances deal with a literary agent who charges a reading fee.

There’s some interesting titbits re: rates of payment for magazines which are quite startling: eg, at the time The Saturday Evening Post paid $750-$3,000 for an original magazine feature, while The Reader’s Digest averaged $2,500. Dryly, the authors advise that Harper’s Magazine rates start at $250:

Which indicates the range for the quality magazines—long on merit but short in circulation.

It’s a very workmanlike collection, on very workmanlike newsprinty-style paper and was clearly aimed at the aspiring author without much means—for it was only $1.45, as the cover proudly proclaims.

Meanwhile, Be Your Own Editor—How to Make Your Stories Sell, published in New York in 1959, is an altogether more elegant number-a trim hardcover, with eye-catching three-colour jacket. And it’s a treasured addition to my collection, for despite its American publication, it was written by a great Australian writer, D’ Arcy Niland, whose classic novel The Shiralee is one of Australia’s best-loved books, and has been filmed several times. Niland, who was married to another great Australian writer, Ruth Park, until his untimely death in his forties (their twin daughters Kilmeny and Deborah Niland became renowned illustrators), was also a highly successful writer of short stories, with more than 500 published, and his advice in this book is doubly precious because it reflects both his vivid personality and the artistry of his work. It’s full of sharp images, such as

Certainly, you can let your ms go in a slipshod condition. There’s nothing to stop you. There’s nothing to stop you eating spaghetti at Joe’s with your fingers, either.

It’s full of pithy observations, snappily delivered, too, such as:

A plot is basically an idea, but an idea is not a plot.

There are others on character, and theme, dialogue, point of view, and lots more, with practical exercises in all aspects of the writer’s craft, much of which is still relevant today.

Any suggestions from readers for books to add to my collection? And what books on authorship have you found interesting and inspirational–whether old or more modern?

I wish I had suggestions for you, but alas, after reading your blog, all I want to do is scour used bookstores for delightful old tomes filled with the writing wisdom of the ages.

One name not on your list might be Lajos Egri, whose ‘Art of Dramatic Writing’ (1946, released earlier as ‘How to Write a Play’) applies to fiction writers as well as playwrights.

On a more mundane note, I depend heavily on antique cookbooks by Alexis Soyer and Mrs. Beeton to get an idea of what my characters might eat, and on those travel guides you mention. Also, I will download, buy or bookmark anything that involves old house plans.

Yes, those sort of books are invaluable for info you just can’t find in modern books on historical periods, aren’t they!

This was fascinating. I don’t have any books to add to your list but I loved reading the blog.

The best book I’ve read about writing is by Stephen King.

I’ve heard this from several people now. Maybe I should check out Stephen King’s book! One I find just fun is Terry Brook’s Sometimes the Magic Works.

Fascinating post! Thank you. I collect children’s picture books from turn of the last century up through 1950’s–everything from early readers to science books. Of course the art work captures each era wonderfully, but what titillates me the most is the frequently bizarre subjects publishers in yesteryear thought suitable for young minds–in many ways, way more adventurous and less politically correct than today.

Wow! This was very cool. I was wondering: Where did you find the books you mention? And, about the self-publishing part, it certainly helps that the self-promoter was promoting Dostoevsky. There are so very few writers of his quality in the land of self-publishing today–but, of course, there are so few of those in the land of traditional publishing today, as well.

This makes me wonder how much my 19th Century books are worth…

Steven, I found the books in local used-book shops(bricks and mortrar ones!) as well as online–www.abebooks.com is a great place to find such treasures (use the ‘advanced search option to narrow down your search, including publication dates.)

I take your point re Dostoevsky–and what was interesting was that he was an established writer at the time he self-published.

Great article Sophie and some interesting quotes from the ‘good old days’.

Thanks for taking the time to write out the quotes. It’s interesting to see what has changed (i.e. agent focus) and what has remained the same. I enjoyed your post. Sorry I don’t have other oldies but goodies to add to your list.

I’ve enjoyed old books on writing as well – it’s surprising how well the advice can be, from Aristotle on down.

W. Somerset Maugham’s Summing Up (1938) is a wonderfully candid (if dry) autobiography of sorts, with much more about novels and plays than about himself.

The Writer’s Digest Guide to Good Writing is an interesting collection of articles from the 1920s to 1990, including pieces from Edgar Rice Burroughs and H.G. Wells.

And one of the best I’ve read is Dwight V. Swain’s Techniques of the Selling Writer, from 1965. Only thing dated about it are a few funny mentions of carbon paper.

Fascinating! I am in love with books on writing, and the more I come across the more I see how universal so much of the advice can be—and how subjective!

I appreciate your need to collect the time worn and vintage ones. I’ve got a wee collection of books on folklore of yore.

Thanks for sharing…

I was delighted when I found the editorial equivalent — Mark Twain’s editing of James Fennimore Cooper. (https://twain.lib.virginia.edu/projects/rissetto/offense.html) In Letters from the Earth, Twain actually line-edits a paragraph from Cooper, cutting it essentially in half. And a lot of Twain’s editorial advice (“Eschew surplussage”) still applies today.