Flip the Script: Write What You Don’t Know

By Jael McHenry | April 2, 2012 |

Last month I kicked off the Flip the Script series by advising writers to backwardize a tired writing cliche and Tell, Don’t Show. For April, let’s take another oft-heard, much-repeated bit of writing advice and turn it on its head.

Last month I kicked off the Flip the Script series by advising writers to backwardize a tired writing cliche and Tell, Don’t Show. For April, let’s take another oft-heard, much-repeated bit of writing advice and turn it on its head.

What are we constantly told? Write what you know.

What should we try instead? Write what you don’t know, of course.

Many beginning writers start out with autobiographical material, whether they’re writing that first story at 12, or 42, or 82. Some people are motivated by the desire to tell their own story first and foremost. Which, if you’re a memoirist, is great — but if you intend to be a fiction writer, it has certain drawbacks. For one thing, it makes you that annoying person in workshop who defends every flaw in his or her story with “But that’s how it happened!” (Thud.) And thus we learn that real life is actually much less believable than the stuff we make up. Sticking too close to autobiography unbalances your characters, locks you into a predetermined plot, and limits you to a mere handful of “valid” topics.

So if you’re willing to grant that just drawing purely on your own experience isn’t the path to great fiction, here’s what you need to consider next — how far should you go into the unknown? You’ve got a few options.

Combine what you know with what you don’t. This seems to be where many of us are most comfortable, and there’s plenty of territory there. If you’ve lived in San Francisco, you don’t need to bend over backwards to set everything you write in Tacoma or Austin or Vancouver instead of using San Francisco as your setting. But if you’re a 28-year-old woman in San Francisco with a job in advertising and six toes on your right foot, you shouldn’t feel like you need to use the job and the age and the toes AND San Francisco. And if you want to write from the point of view of a male narrator, you’re free to do it. You should do it. You may find that the two of you have something in common (the job, maybe, or the toes), and that may make you more comfortable stretching yourself in areas where you don’t.

Nudge over into adjacent territory. I was on a panel last month with Tayari Jones, who wrote the extremely well-reviewed novel Silver Sparrow, about two sisters, one of whom is her father’s acknowledged daughter and one who is part of his secret, second family. Her material wasn’t autobiographical, but she could imagine the story of that second sister based on the experience of others she knew, and she summed it up beautifully with this quote: “If you know what it’s like to be trapped in an elevator, you can write what it’s like to be trapped in a spaceship.” We may live our whole lives without anything extreme happening to us, but we can take things we’ve felt on a small scale and multiply the intensity to put them on a larger scale. It’s more fun to write and it’s more fun to read. That could mean drawing on the experience of being bitten by a dog to write about being bitten by a zombie, or it could mean imagining what divorce might be like based on your memories of a bad college breakup. We’re writers. We imagine. If you have a kernel to imagine from, use it, and it’ll grow into something new.

Leap. And then there’s the option of just going completely, totally, wonderfully off the rails. Nothing should hold you back from this. Do you want to write about being a 16th-century Carmelite nun? A construction worker? A dog? Give it a shot. Just because it’s foreign to your experience doesn’t mean you’re not capable of pulling it off. But the more deeply you want to inhabit the character, the more research you need to do on the details of that person’s (or canine’s) life. The fact that it’s fiction doesn’t absolve you from doing real research. And maybe that’s why you’re advised to write what you know in the first place — it’s harder to get that wrong.

But writing what you don’t know? It’s so rewarding and so powerful when you get it right.

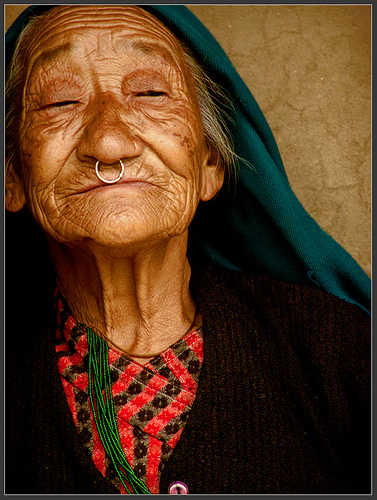

(photo by Sukanto Debnath)

“We’re writers. We imagine. If you have a kernel to imagine from, use it, and it’ll grow into something new.”

Bingo. Great post, Jael!

Great stuff – I am loving this new series.

And a major amen to pointing out the danger of the “but that’s how it happened” defense. A hard but very important lesson for writers to learn is that just because something may be true, that doesn’t automatically make it compelling, or even interesting.

Like you said, “We imagine.” For a novelist, I think that’s one of our primary responsibilities.

I think it could be something very fun to try. And probably something many have tried without realizing, especially as beginners or children. How many kids writer detective stories with absolutely no idea of how detectives work? But with what they do or don’t say, we get the picture and we accept it, because they don’t know enough to get it right, but they know little enough not to get it wrong either. Then as they get older, they start doing more research about detectives before they write their detective stories and they start getting it closer and closer to right.

Jael, thanks for sharing this perspective. I’m not a fan of writing autobiographical fiction, but on some level we inject our hopes, dreams, aspirations and fears into our work. A presenter at a workshop made a great point that is pertinent to this post: there are a lot of things we don’t know we know. This is a great way of looking at this topic. Thanks again.

“If you know what it’s like to be trapped in an elevator, you can write what it’s like to be trapped in a spaceship.”

I love that. It’s so true.

Thanks for this piece! Though, I must say, I’ve always wanted to write something that was not autobiographical because, honestly, my life is far too boring for fiction. And the whole point of writing fiction is to explore new viewpoints, and to have the chance to inhabit someone else’s life and adventures.

Write on! :)

And more entertaining too. Especially if you’re a pantser and don’t know where you’ll end up. I love the way you are playing around with the generally accepted wisdom. If we don’t push the envelope we may never find what works best for us, right?

Oh Jael, this post is perfect! It offers a spectrum of “what you don’t know” and ways to write about it. And funny that you mention reversing the gender, b/c I literally thought of that last night as a way to distance myself from something that happened to me that I really want to write about, and it seems to be doing the trick.

“We’re writers. We imagine. If you have a kernel to imagine from, use it, and it’ll grow into something new.”

Yes. That.

So true. I once attended a reading of a well respected Canadian author who was talking about his book that was a fictionalized version of a part of his family history. During his talk he detailed a true event between the main characters that was astonishing- but NOT in the book- as it would not read true. That has stuck with me.

Thanks, Jael. As someone who likes to explore the unknown in my fiction, I hate the whole write-what-you-know adage. It is fiction after all, and I think there is too much expectation these days that all fiction must be true. I was in a class once discussing a Jim Crace novel in which he had invented a water bug. Half the class discounted the work of fiction because nothing came up about the bug in a Google search.

So right, and that’s a shame. So much really fun fiction requires the reader to take a leap of faith. To play along, if you will.

I’m glad I started writing years, even decades, before I ever heard those words (write what you know) strung together and aimed at writers. My first story, written at age 9, was about a Lakota girl who finds an injured horse on the prairie and nurses it back to health. I was a white girl living in a suburb outside the DC Beltway. Horses scared me. They still do. But I’m still writing frontier adventure stories full of them. Half the fun for me is learning to know what I’m writing about. You’re right about the amount of research that sometimes takes!

Write what you know: emotion

Know what you write: everything else

Rather than “write what you know” I much prefer “write what fascinates you.” That has enabled me to write novels from the point of view of a girl in ninth-century Mayan times or ancient Egypt, and to use a 13-year-old boy as the narrator in a series of ghost stories. It may require extra research, but that’s part of the fun, if the topic is one you love!

I’m piggy-backing off of what you and Keith said about being a slave to the truth of the situation. As a historical fiction writer, I wrestle with this issue all the time. Do I include that fact? Do I gloss over his affair? Crap, that word didn’t exist during this time period, etc. Thank God for the imagination! And thank you for the great reminder.

The thing that helps with writing what you don’t know is that humans are just that, human, and have certain experiences and emotions that are universal throughout time and in different locations. Like you said, being trapped in an elevator isn’t all that different than being trapped in a spaceship, or being trapped in a fourteenth-century abbey, etc. Start with the little bit you do know, do some research and a lot of thinking, and expand into what you don’t.

I love this post, especially because I do love diving into the unknown–into the medieval world, or the land of the fey, or any number of other times and places.

Don’t you think that “what you know” includes all that you’ve read in novels and seen in movies? For example, I consumed bales of Western, science fiction, and fantasy novels when I was a young ‘un. As a result, I have no hesitation in answering a what-if question like “What if there was really a way to do magical things that we just don’t know about?” with a novel (“Finding Magic”)

Or, even more fun, what would it be like to be a tomcat who is turned into a vampire? Having known a score of kitty-cats, it was just a matter of channeling them in “The Vampire Kitty-cat Chronicles.” Point is, what we “know” can be vast, and our imaginations need know no bounds.

In SF and fantasy it is often impossible to write what you know, because more often than not, a writer is creating a whole world. For me writing what I know has always boiled down to the human empathy I can feel for my chars, and their worlds.

I love that bit about if your’re trapped in an elevator – you can understand what it’s like to be trapped in a spaceship. I think this applies to readers, too.

Thanks for this series. It is thought-provoking.

Great post, Jael. I like what you said about taking the kernel and using that with a little imagination to make it grow into something bigger. My book starts with a couple who lose their baby at birth. It never happened to me, but because I have two children, I know what it’s like to love a child more than life itself. I used that to tell my tale.

Patti

Spot on advice!

Great post! I wrote about this last month at The Pink Heart Society, but you’ve said it much better, Jael.

Abbi :-)

When I started writing, only a blog mind you, I did it as a way of making a name for my new company. I blogged more or less every day and to be honest I wasn’t the best. I didn’t know the business good enough, I certainly wasn’t a good enough author but writing about it made it so much simpler for me to grasp.

Even though I’m not very proud of those early posts they forced me to learn. This might not be on the same page as having a character of the opposite sex or being trapped in a spaceship but I really agree. By writing about those things that we’re not really mastering we can write more interesting and also evolve.

I sometimes give talks at elementary schools, and I always tell the kids they can still write what they know even if their story is in a strange setting with all different kinds of characters. I tell them they can write what they know about being scared, for example. Even if they were scared only because they heard the cat knock something over at the bottom of the dark basement stairs they can use that to tell how their character is scared because she’s being stalked by werewolves, or kidnapped by pirates, or spying on a criminal mastermind, or whatever. I’ll definitely be quoting Tayara Jones from now on!

Bernadette Phipps Lincke commented that in sci-fi and fantasy it’s impossible to write what you know, but I’d turn that around. In some ways we can’t help but write what we know: what we know about human emotions and what fills us with wonder, and what we know about beauty and mystery, and, as she says, human empathy.

Thanks for this post. It’s always nice to find like-minded writers!