A conversation with Brunonia Barry, part 2

By Therese Walsh | May 8, 2009 |

Brunonia Barry, author of the hit debut novel, The Lace Reader, has amazing stories to tell–and I’m not just referring to her fiction. If you missed part one of the transcript of our phone interview last week, you may want to check it out now, to hear all about the fantastical dream that inspired The Lace Reader. This week, she’ll speak about her success–as one piece of luck (like working with Hemingway’s last editor) lead to another, lead to a nearly unprecedented bidding war and book deal. We’ll also hear about some of the writerly trials she went through along the way, including the twists delivered to her by her muse, and her fear of tackling the male point of view.

For those unfamiliar with the premise of The Lace Reader, here’s a review by Publisher’s Weekly that’ll help you to better appreciate this part of the interview.

Starred Review. In Barry’s captivating debut, Towner Whitney, a dazed young woman descended from a long line of mind readers and fortune tellers, has survived numerous traumas and returned to her hometown of Salem, Mass., to recover. Any tranquility in her life is short-lived when her beloved great-aunt Eva drowns under circumstances suggesting foul play. Towner’s suspicions are taken with a grain of salt given her history of hallucinatory visions and self-harm. The mystery enmeshes local cop John Rafferty, who had left the pressures of big city police work for a quieter life in Salem and now finds himself falling for the enigmatic Towner as he mourns Eva and delves into the history of the eccentric Whitney clan. Barry excels at capturing the feel of smalltown life, and balances action with close looks at the characters’ inner worlds. Her pacing and use of different perspectives show tremendous skill and will keep readers captivated all the way through.

Enjoy!

Part 2: Interview with Brunonia Barry

TW: What were the major turning points for you as you worked from concept to finished product?

BB: Well, one of them was moving to Salem. That gave me the idea to pursue the hero’s journey. Another was when the ending to my book changed.

TW: Let’s talk about that—the ending and how it evolved for you.

BB: It’s crazy. I’d been editing the draft as I went, in part so that I had polished pages to show my husband and writing group. I had all these extraneous things going on in my story, and I didn’t feel like they made sense to what I was writing. About two-thirds of the way through the draft, the ending I’d planned changed. I’d had it outlined, but it didn’t matter. I remember getting to the big surprise—a surprise to me as well—and yelling, “No!” My husband came running into my office to see what had happened. What a shock. I thought I knew the story I was writing, but Towner’s character had taken over. In retrospect I would say that I’d always been writing it so that the true ending would work—I just didn’t know it.

TW: How long did it take for you to accept that this was the true ending?

BB: I had to leave the story for about two weeks. I got up and walked away, and said, “I don’t know what I’m doing anymore.” When I came back to it, I saw that all of those extraneous details and clues that I’d been bewildered by earlier now worked. I did know this was a book about intuition and perception, and when the ending came to me, I realized this was really a book about intuition and perception, and that I needed to trust mine. If you believe in the muse…

TW: There’s a question.

BB: Yes. Who’s writing this? Am I writing this myself or am I being inspired? What I tried to write in Hollywood were cool, trendy things that really weren’t me; I think that’s why I could never finish them. When I sat down to write this book I said, “Let me write something that’s important at least to me, that will resonate at least with me and my life.” It wasn’t a story that I would’ve picked; it just came to me. If you believe that—that you have a muse and not that you are the muse, or as Elizabeth Gilbert said, you are not the genius, but you have a genius—then you have to trust the process.

[Note: readers, you can watch Elizabeth Gilbert’s fantastic speech on creativity HERE.]

Another major turning point for me was to decide to quit any outside work I was doing. That was huge. That’s when I was doing the rewrite. I started it and realized I couldn’t continue working on all the other things that were taking me away from the book. I had a little money saved, but saying to your husband, “I’m quitting,” isn’t easy. I told him as we were stepping onto the public part of a train to have dinner. He just said, “Uh, okay.” When he read the final draft, he liked it enough that he wanted to invest the time to self publish it. That was a shock.

TW: And he became your business manager, isn’t that right?

BB: Yes. He was really my business manager and my first publisher. I think he typeset the first book himself, too.

TW: Talk to us about what happened with Tom Jenks. Was meeting up with Hemingway’s last editor one of your turning points?

BB: Being guided by Tom Jenks was definitely one of the turning points. You should definitely check out his website, by the way. It’s amazing who he’s edited. He was conducting a seminar in Boston and I think he had twelve participants originally. As I remember, there were four spots left, so I submitted a chapter from the book to see if I could get in. I knew I needed to workshop that particular chapter, and I wanted someone who was very good. I waited for a while, and didn’t hear from him. When I did hear, he said, “What the heck is this? Send me more,” and I did.

We ended up kind of coming to an agreement that I wouldn’t be in the class but that we’d work privately together. That was amazing, because what he really did was cut through the problems. I had a whole first draft at that point, and it wasn’t working but I didn’t know why. He said, “The reason it’s not working is that you have an unreliable narrator at best—crazy at worst—and everything happens at the end of the story because it’s entirely in Towner’s point of view. I think you should add other points of view, and the one I think you should work on is Rafferty.” I didn’t want to, because Rafferty is a male, and this was my first novel and I didn’t feel comfortable. He told me that I should because Rafferty was my best character.

TW: I’ve had some writing guy-speak issues, too. So how did you tackle it?

BB: It wasn’t easy. I modeled the way Rafferty speaks on people I knew. Since so much of character is revealed through dialog, I spent time listening to men. There were a lot of renovations going on in my house then, and I was hearing a lot of male conversation. It had a certain attitude that Rafferty has. I also listened carefully to my brother, who’s an attorney but who used to be a plumber. I just thought, a cop fits in there somewhere. So I modeled Rafferty a bit on these subcontractors and a bit on my brother and also a bit on my husband, who’s a software programmer. I noticed patterns in speech. The rest of it was what I’d think being a male is like, and I don’t know if it’s true at all. But Tom Jenks seemed to think it was authentic, so I went with it.

TW: You said you noticed patterns in male speech. What sorts of things did you notice?

BB: One thing that stood out was a kind of sarcasm between males. In many cases, Rafferty uses it with Towner. Rafferty’s a bit self-effacing, but he’s also a bit sarcastic. I always consider it New England sarcasm. I lived in California and they don’t do things quite the same way there; everyplace is a little bit different. The thing is, translators don’t have any clue how to translate things like this, because they just don’t do it, they don’t get why someone would say, “Date much?” to the person they’re on a date with. Things like that. You know, how is that going to win a person over? But in New England, people can be very polite, but when they get to know you a little, they can get…they tease you.

TW: What were the other major lessons Tom Jenks imparted? How did he help to improve your craft?

BB: Tom didn’t say, “Do it this way.” He said, “This is what I think you should explore.” He said that one of the things you have to do is get the reader there sooner. You know, include them, and that they really won’t hang in there unless you do. I took some chances by not introducing Rafferty until the middle of the book, and then also by introducing two new points of view toward the end of the book—something you absolutely shouldn’t do, but it worked for this book.

We talked many times. I would get so overwhelmed because he’s so knowledgeable. He would direct me to read a page of this or a work to see how another author handled something, and I just thought I was out of my league. I used to pretend that there was someone at the door so that I could get off the phone with him. He caught on to that pretty fast. I just felt I was in the presence of greatness and didn’t know what I was doing. I listened to what he said, though, and then I went away for two years. He didn’t see my work again until it was published by us, and he said he liked it.

TW: Yours is one of the best first-sale stories I’ve ever heard. Will you speak to how you were published and how you used book clubs to help polish your novel?

BB: Yes. I had submitted fifty pages long ago to agents. I hadn’t finished the manuscript; I submitted way too early. But it took about a year to get responses to those submissions, which seemed a very long time. My husband and I had a little software publishing company called Smart Games. Software has a different route for marketing, but you do a lot of testing of the software. Essentially we were used to using focus groups and individuals, and I liked doing that—kind of a combination of software testing and workshopping. When I seemed reluctant to submit to agents again, my husband suggested, “Why don’t we self-publish your book?” And that’s what we did. It seemed like a good plan. We’d create a local book for Salem and the surrounding areas, and then if it did well enough, we’d take it to a larger publisher. That’s what our plan had been.

How hard could it be? We had no idea. We were totally naïve.

But there was a huge amount of magic in the way it happened. One of the things I did to test the story was take it to a local bookstore—an independent bookstore in Marblehead—where I had done readings for The Beacon Street Girls [note: a series plotted by editors for a book packager]. The owners had asked me before, “So what are you really working on? All writers have their own novels. Show us when it’s done.” When I told them we were going to self-publish my book, they squirmed a little bit. I asked if they could recommend a book club. They had thirty book clubs, I think, that they sold to, and they would post what they were reading every month. I asked them if they knew any that would want to read a new writer, and read a book in a box, basically. They thought about it for a week, and then called to say they had a group that would love to do that and be involved.

I hosted ten women at my house. What I asked them was essentially what Tom Jenks and I had talked about, which was “Where do you stop reading?” I’d finished that rewrite and wondered what made them put the book down. It was helpful, because you just never know, but when you start getting the same answers, you listen. They told me new things that were confusing to them or that they didn’t like. I said “Be brutal.” I have kind of a thick skin, and they knew I wasn’t going to cry. And they were brutal; it was brilliant. At the end I asked, “Would you recommend this book?” And they said, “Oh, god, we’ve already recommended it! We can’t wait until it comes out.”

By the time we came out with the book, I think there were already 37 book clubs reading it, and it wasn’t just New England; it was all over the country. So it spread quickly and got a little out of our hands quickly, which was kind of a good thing.

TW: Would you consider going to the book groups and receiving their feedback one of the major turning points for you and this book?

BB: Yes, I would. I think that was the next major turning point. The other thing that happened was that we hired a public relations company, and they submitted the book to Publisher’s Weekly. For a small press publication, we weren’t sure who would review it, but Publisher’s Weekly did. That was the first bit of magic, really. I think that we existed as a small press really made a difference in getting that review; our intention was not just to self-publish.

Then, oddly, we started getting calls from agents, but it wasn’t to get a bigger book publisher; it was to get a movie deal. I thought it was a bit early for movie options, so I called some friends in Hollywood to talk about it: “I don’t know these agents, I don’t know what to think about this.” It was a buying season in Hollywood around Thanksgiving. They said, “They’re buying now, but they won’t be buying again for the next six months.” They thought that The Lace Reader was a good book and would make a good film, but asked, “Who’s this Flap Jacket Press?” And when we said that they were, they said, “Oh, no, not good. Do you mind if we send it back to New York to get you a big book publisher?” So that’s how that happened. Actually, the book wasn’t out when this all started; the Publisher’s Weekly review came out early. The book wasn’t on the shelf until early October, and by mid-October, we had the deal and the first 2000 copies had sold through and we weren’t allowed to put more out there. So it happened pretty quickly. When the New York literary agent called me—Rebecca Oliver—she said, “I love this book and want to put it out to auction. Do you mind?”

TW: Funny! What do you say to that? “Yes. Yes, I do.”

BB: Exactly. So we had a five-day bidding war, and in the end I got to choose. Invitations were made to me in the last twenty-four hours or so, so we didn’t leave the house much. We ordered a lot of pizza.

TW: There were five major publishers bidding on the book—is that right?

BB: Yes, and then it went down to three, and I chose. It was all pretty similar from a financial standpoint. I talked to some great editors; I loved them all. But I felt that William Morrow was the best fit for me on every single level. I felt really lucky to be with them.

TW: Once with them, was there an editing process? What was it like?

BB: There was. What they said was I didn’t have to change a word—they all did. But then I asked, “What would you change if you could?” I mean, if you’re getting to work with a good editor, you should work with them, you know? Laurie Chittenden said, “I would reverse the first two chapters.” The first chapter started with her getting a call in California. From a literary standpoint, I like that chapter better; it’s a little more poetic than the next. But what she liked and what tells more about the book is what was in the next chapter, “My name is Towner Whitney. Never believe me, I lie all the time, I’m a crazy woman.” And that’s true, you know? She said, the first lines of books are quoted everywhere, and this one will be. She was so right; that was brilliant. So I had to figure out how to reverse those chapters, and that was a bit of a challenge—not getting the second chapter to become the first one, but then taking what I’d had in the first chapter and weaving it into the second chapter. But other than that, it was really just clarifying some things along the way, which helped a lot. Sometimes it’s hard because you might’ve written something very clever, but it just doesn’t go.

TW: Right, because the reader doesn’t need to know about it.

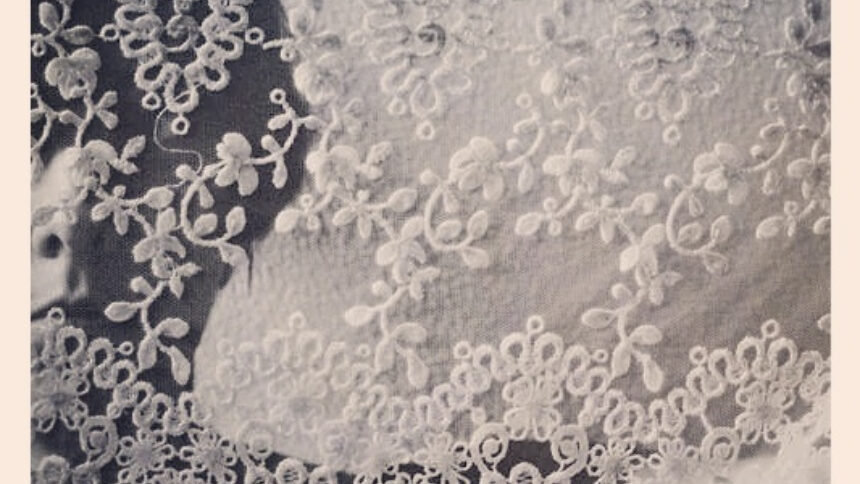

BB: Exactly. There’s a lot in The Lace Reader that the reader doesn’t know. That sometimes represents the gaps Towner has in her memory, but there are also gaps in the book on purpose. There’s as much importance in what’s not on the page as what is, and that’s like reading a piece of lace—when the spaces become just as important as what’s there before you.

TW: There is a lot going on in your book with the subconscious and conscious mind and the idea of an underground–with those hidden passageways and rabbit holes and things that are just out of reach. One way to look at it, I think, is that your characters have each been through something like a war–certainly Towner, but also Rafferty and May and Jack and Emma—and because of that, there are these big cavities in personality and memories, even what you think you want and need out of life. How much of this was conscious for you as you were writing it?

BB: I think the idea of lace reading is, in a certain sense–well, the gaps are important, the subconscious mind is important, so that was there. And then as I learned about the history of Salem and the tunnels, it made sense. I don’t think it was conscious until you said it–the war imagery–but you’re absolutely right. The images and the grouping of images and the idea of underground, underwater, gaps, holes, places you don’t usually recognize, and battle scars… Battle scars is huge. The image of that is huge. But I wouldn’t have classified it that way until you said it, so I like it a lot, it’s great.

TW: Well, you did such a great job showing battle scars via characterizations and by referring to those underground tunnels in personalities. I loved the surprises–how you set us up to step into them like those hidden rabbit holes–and I loved the rabbit holes.

BB: Rabbit holes were always there. What’s underground and what’s underwater was important in the book, and the rabbit holes were important to me–especially when a new rabbit hole appeared that Towner hadn’t noticed before. That was the book for me, in that particular sentence.

TW: That moment was significant—her disorientation. Was the meaning of the rabbit holes always clear to you?

BB: I think I knew what the rabbit holes represented–and the island I based this on had rabbit holes everywhere. “Down the rabbit hole” means something literarily, so I’d always thought of them that way. And the rat holes, too. The rats in the book were really important to me. I had so much empathy for them that they almost became mirrors of the characters.

TW: Oh, interesting. How so?

BB: Well, I don’t want to give anything away, but at one point some of the rats get stuck. And this happens sometimes to people, too; they get stuck and cannot survive it. It’s very hard when you say, “I have empathy for the rats.” People don’t get that. But for me, that was the saddest moment in the book. I’m not sure I knew what they represented, but the scene made me cry. On opening night, I read at a center for abused women and children, and they had read the book. Just the things they said, I was so glad I’d written the book. This is a book about survival.

Click HERE for the final part of my conversation with Brunonia Barry!

What an awesome and fortuitous journey!

And I’m completely intrigued by this book. What an original idea! Thanks for this. It’s a great, inspiring way to start the day. :)

this interview is getting more complicated!! look forward to next week. thanks,

This was a fantastic interview! Its so good to read about other authors pitfals and ingenious moments, and you seem to have had some fantastic ones.

Keep on writing, Buronia, and best of luck to you!

Regards,

Terry Tibke

Wow. Terriffic interview. Can’t wait to read this book.