Go Primary!

By Sophie Masson | September 17, 2008 |

When you’re writing a novel set in a period that’s not your own, research is an inescapable part of the equation. Not that it bothers me—I love setting off on a journey of discovery into the ‘foreign’ yet teasingly familiar country that is the past, and on the way learn lots and lots of things, which will often set me off on new and intriguing paths. It is indeed often so much fun that it can be hard to tear yourself away from the research to begin the hard work of the book itself! And you also have to temper enthusiasm with temperance—to know the point at which enough research becomes too much. And not to paralyse your creativity with too much emphasis on logistics or facts—to remember you are not writing a historical textbook, but a historical novel. Over the years I’ve become familiar with those tipping points and now, by instinct, know when to stop—and not to become enslaved by historical fact. The trick is to learn enough facts and absorb enough cultural atmosphere to feel as though you are comfortable in that period; but not to think you need to know absolutely everything—after all, you don’t even know absolutely everything about your own times!

When you’re writing a novel set in a period that’s not your own, research is an inescapable part of the equation. Not that it bothers me—I love setting off on a journey of discovery into the ‘foreign’ yet teasingly familiar country that is the past, and on the way learn lots and lots of things, which will often set me off on new and intriguing paths. It is indeed often so much fun that it can be hard to tear yourself away from the research to begin the hard work of the book itself! And you also have to temper enthusiasm with temperance—to know the point at which enough research becomes too much. And not to paralyse your creativity with too much emphasis on logistics or facts—to remember you are not writing a historical textbook, but a historical novel. Over the years I’ve become familiar with those tipping points and now, by instinct, know when to stop—and not to become enslaved by historical fact. The trick is to learn enough facts and absorb enough cultural atmosphere to feel as though you are comfortable in that period; but not to think you need to know absolutely everything—after all, you don’t even know absolutely everything about your own times!

When I do research into a historical period, I look at a whole range of source materials. Though I do briefly look at secondary sources such as general histories of the period (and also books focusing on particular aspects of that period, say, clothes, transport, weapons, social or cultural developments, etc), the major part of my reading is done in primary sources: novels, plays, poetry, non-fiction of that period, letters if any have survived, and contemporary magazines. These give a much better and warmer feel for the actual atmosphere of the times than books written later, with the benefit of hindsight. You get a real sense of how people thought and spoke—and it can be really surprising.

For instance, I’d assumed that the word ‘cool’ in the sense we use it today was a fairly modern usage. Not a bit of it! It was used the same way in Victorian times: in Wilkie Collins’ The Moonstone, at one point someone exclaims, ‘Cool!’ meaning ‘Wow’; in Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations, a ‘cool few thousand’ is inherited. Similarly, the Victorian term for a police detective (which also appears in Great Expectations), a ‘jack’ is still in common use in the Australian criminal underclass, as evidenced in the very graphic, very modern hit TV series, Underbelly (which is based on real events in Melbourne’s gangster-land). Along with ‘copper’ and ‘pig’–the latter of which has been in use as a derogatory term for the police, since the sixteenth century.

For instance, I’d assumed that the word ‘cool’ in the sense we use it today was a fairly modern usage. Not a bit of it! It was used the same way in Victorian times: in Wilkie Collins’ The Moonstone, at one point someone exclaims, ‘Cool!’ meaning ‘Wow’; in Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations, a ‘cool few thousand’ is inherited. Similarly, the Victorian term for a police detective (which also appears in Great Expectations), a ‘jack’ is still in common use in the Australian criminal underclass, as evidenced in the very graphic, very modern hit TV series, Underbelly (which is based on real events in Melbourne’s gangster-land). Along with ‘copper’ and ‘pig’–the latter of which has been in use as a derogatory term for the police, since the sixteenth century.

I’m not saying one should necessarily copy 19th century novel structure in order to write a modern novel set in the 19th century — any more than 19th century novelists like Alexandre Dumas used seventeenth-century structures to write novels set at that time. But the flavour of a time is strongly there within those fictional worlds, and it can’t help but influence you as you write your own book. For instance, staying in the 19th century, there is a dominant lightness of touch, an elegant irony in the style of many novelists, which combines with Gothic romance, a touch of melancholy, intensive and sometimes extreme characterisation, comic elements and strong stories to create a rich and engaging atmosphere that for many readers typifies the novel of the 19th century. The writers are all different and express their own thing, of course; but there is still something we come to recognise, and which even in a modern novel set at that period, we unconsciously look for.

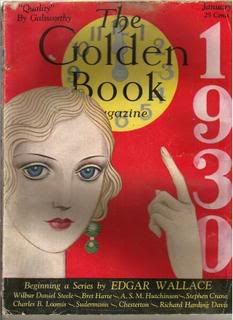

As well as novels, plays and poetry of the period you’re writing about are well worth getting into—and also the more ephemeral non-fiction, both in book and magazine form. It may sound surprising at first glance, but non-fiction is in fact a good deal more ephemeral than fiction or plays or poetry. That’s because of course it concentrates on current affairs and cannot predict what will come after it. What is accepted wisdom in one generation is often upended in the next. But it is still intensely fascinating and absolutely necessary as reading material for a historical novelist. For instance, when I was writing The Case of the Diamond Shadow, my mystery novel set in the 1930’s, I bought, second-hand, a great many books and magazines from the time. All sorts of things, from film and fashion magazines to handbooks of forensic pathology, true-crime books and magazines, literary magazines, guide-books to London and Paris, political tracts, and more. As well, I had my grandparents’ photographs to pore over, and pictures and photos in the various contemporary books and magazines (the visual material is almost as important as written things, and should never be overlooked).

As well as novels, plays and poetry of the period you’re writing about are well worth getting into—and also the more ephemeral non-fiction, both in book and magazine form. It may sound surprising at first glance, but non-fiction is in fact a good deal more ephemeral than fiction or plays or poetry. That’s because of course it concentrates on current affairs and cannot predict what will come after it. What is accepted wisdom in one generation is often upended in the next. But it is still intensely fascinating and absolutely necessary as reading material for a historical novelist. For instance, when I was writing The Case of the Diamond Shadow, my mystery novel set in the 1930’s, I bought, second-hand, a great many books and magazines from the time. All sorts of things, from film and fashion magazines to handbooks of forensic pathology, true-crime books and magazines, literary magazines, guide-books to London and Paris, political tracts, and more. As well, I had my grandparents’ photographs to pore over, and pictures and photos in the various contemporary books and magazines (the visual material is almost as important as written things, and should never be overlooked).

I also watched a good many films from that time, and listened to its music. As well as being wonderfully entertaining, this all immersed me completely in the atmosphere of the time, making me feel almost as though I were actually living in it, becoming so familiar with it that it was easy then to create exactly the kind of atmosphere I wanted for my book. Magazines are particularly good for recreating in your mind all those sorts of elements that people forget about, once fashions change and time moves on. It’s not only their stories and articles that are such a rich source of atmosphere—but also their advertisements. They are the small beer of daily life, but looking at them, you get a sense of people’s daily concerns, fears, hopes, and wishes.

Similarly, when researching The Understudy, the novel I’m writing at the moment, which is set in the London theatre world in 1860 (and which features a cameo appearance by both Dickens and Collins) I’ve been living in the rich climate of the Victorian novel, plus reading a good many Victorian works of non-fiction. From https://www.abebooks.com/, my favourite source of such material (and which is a virtual shopfront of hundreds of 2nd hand bookshops from across the world), I also ordered original, bound copies of Dickens’ magazine of the time, All the Year Round, as well as Punch, and I’ve also been dipping into bound collections of magazines I already own, which come from that time—such as Blackwood’s and one called London Society which only seems to have lasted a few years (I am an inveterate haunter of second-hand bookshops and am always picking up odds and ends). Magazines proliferated at that time, each of them aimed at a different niche market, each of them featuring short stories, serialised novels, poetry, and articles on every conceivable subject. Some, like London Society, were profusely illustrated; others, like All the Year Round, were not. But they are absolute goldmines of wonderful atmosphere, unusual facts, stray bits of ideas and dialogue, and they will often spark you off on trains of thought you might never otherwise have considered if you hadn’t picked up that magazine.

Similarly, when researching The Understudy, the novel I’m writing at the moment, which is set in the London theatre world in 1860 (and which features a cameo appearance by both Dickens and Collins) I’ve been living in the rich climate of the Victorian novel, plus reading a good many Victorian works of non-fiction. From https://www.abebooks.com/, my favourite source of such material (and which is a virtual shopfront of hundreds of 2nd hand bookshops from across the world), I also ordered original, bound copies of Dickens’ magazine of the time, All the Year Round, as well as Punch, and I’ve also been dipping into bound collections of magazines I already own, which come from that time—such as Blackwood’s and one called London Society which only seems to have lasted a few years (I am an inveterate haunter of second-hand bookshops and am always picking up odds and ends). Magazines proliferated at that time, each of them aimed at a different niche market, each of them featuring short stories, serialised novels, poetry, and articles on every conceivable subject. Some, like London Society, were profusely illustrated; others, like All the Year Round, were not. But they are absolute goldmines of wonderful atmosphere, unusual facts, stray bits of ideas and dialogue, and they will often spark you off on trains of thought you might never otherwise have considered if you hadn’t picked up that magazine.

Of course, it’s easy, and fairly cheap, through second-hand bookshops and/or the Internet, to get hold of copies of magazines from the 20th and 19th centuries (though the early 19th century is not so easy). Old books are also easy to get hold of, either as reprints, or if they’re out of print, through the Internet or second-hand bookshops. You can track down just about every title now—the Internet has certainly been a huge boon for the historical novelist. Of course, earlier periods are a little less rich in source material — at least in ephemera, such as magazines and the like — but there’s still lots and lots of fiction and non-fiction from those times available as reprints or archived on the Web in various scholarly websites. When I was researching a trio of novels set in the 12th century, for instance, I read collections of 12th century narrative poems, bestiaries, (the natural history of the time), herbals, travel books and many more such works that have survived down to our day, as well as looking at buildings, statues, paintings, engravings and listening to music from the time.

The point I am trying to stress in all this is that though secondary sources can be useful quick references, there is no way they match the immediacy and richness of the primary sources. Immersing yourself in them, you not only get a feel for the atmosphere of the time, but you also gain a new respect for and understanding of its people, because you’re not looking down a telescope at them, but you’re right there, in their midst. And that, in my view, helps a writer to create much more interesting and believable characters: always the life-blood of any novel, no matter which genre you are writing in.

I love primary historical sources, and you are so right, there’s nothing for it in terms of authenticity of detail. For the historical I’m working on now, I’m using broadsheets. I love getting into the guts of material culture, language, and the preoccupations of the era. All that from a advertisment.

Great post and good reminders, Sophie!

I write stories set in modern times, but I am a researcher at heart and always love digging into whatever sources I can find. It seems the deeper you dig, the richer the story becomes.

Thanks for the post, Sophie!

Whoa, this is a long one…

Anyway, I think you have some great points! I actually just finished a really disappointing historical novel — disappointing because it was so rich with “historical,” and not with much “novel.”

Great post! For my research (WW2 America), there is a plethora of primary sources – one being my own grandmother. :-)

I also love looking at magazines of the time – they really convey the sense of the period.