Killing Darlings

By Therese Walsh | July 8, 2008 |

I’d been waiting for my fabulous new agent’s notes for tightening my manuscript, and I received those comments just last night. Up to that point, I’d half-convinced myself that she’d email to say she was crazy before and had decided she couldn’t possibly represent such a pile of lawn droppings. Instead, she said she liked the story even more after the second read. (Aren’t all writers neurotic?)

I’d been waiting for my fabulous new agent’s notes for tightening my manuscript, and I received those comments just last night. Up to that point, I’d half-convinced myself that she’d email to say she was crazy before and had decided she couldn’t possibly represent such a pile of lawn droppings. Instead, she said she liked the story even more after the second read. (Aren’t all writers neurotic?)

So after I got past the first reassuring graph, I leaped into the heart of the matter: the revision notes.

I was pretty much prepared for anything since I’d already been critiqued by people from all walks of life, with all sorts of opinions on my plot, characters, dialogue, etc… And as I read through Elisabeth’s list, I thought that most of her suggestions were easily doable. But a few ideas made me freeze up. Cut what? How could I? I’d lose some…

atmosphere

poetic lines

funny asides

clever shades of grey

clever stylistic stuff

clever banter…

Okay, I got it pretty quickly. These were a few of my darlings. And maybe I didn’t really need them. And maybe they didn’t serve the work as well as they served my ego.

So you know me; I grabbed a book, hoping to find camaraderie and wisdom in another writer’s experiences. I didn’t have to look far.

James Michener, in his now out-of-print Writer’s Handbook, wrote at length about his editorial process and cited example after example of editorial feedback and his response to it. Here’s one of his original graphs, an outtake from his memoir, The World Is My Home:

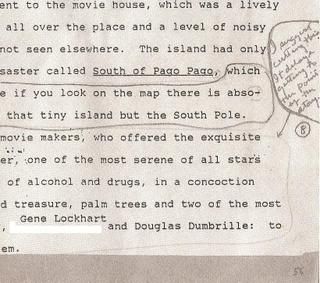

But I was enjoying myself in Papeete, for in the early part of the evening we all went to the movie house, which was a lively scene with young people all over the place and a level of noisy involvement that I had not seen elsewhere. The island had only one film, a colossal disaster called South of Pago Pago, which was interesting, because if you look on the map there is absolutely nothing south of that tiny island but the South Pole. This did not deter the movie makers, who offered the exquisite but doomed Frances Farmer, one of the most serene of all stars but an incurable addict of alcohol and drugs, in a concoction featuring sharks, buried treasure, palm trees and two of the most conniving villains ever, Gene Lockhart and Douglas Dumbrille: to see them was to hate them.

Michener’s editor circled the last part of the graph, beginning at “This did not deter the movie makers.” The note says, “I suggest cutting this. It delays getting to the point of the story.”

On that critique, Michener wrote, “To few current writers could this criticism be more frequently applied than to me. I love the rich embellishment of a statement, the marshaling of arcane data, the retelling of illustrative incident, and the hammering down of the point I seek to make. Readers have constantly thanked me for that approach to storytelling; editors have properly warned me against redundancy. I have tried to follow a rule of reason and have profited from editorial advice. In this instance I wanted to refer to that delightful actor Gene Lockhart because I had recently acted on an informal stage in Belgium with his daughter, June. The passage could be cut. Sorry, June.”

Earlier on the same page, his editor slices part of a sentence, a description of a man who is “a kind of elf.” That was the bit that was left bleeding on the cutting room floor. Michener wrote, “I surrendered the phrase, but not happily.”

So I guess this is my guiding light as I move into this end-stage of editing: Can the phrase/graph/thread/scene be cut or tweaked–happily or otherwise–without hindering the story? Will reworking it better serve the work?

I have to admit that I’m a little weary of editing at this point. But as Michener points out, editing doesn’t end until the book is printed and sitting on a shelf somewhere. Editors and copy editors will have a go at it–or several goes–and you, the author, will tinker with it until someone rips the manuscript from your bleeding, perfectionistic, type-happy fingers. Because each stage of the process offers new opportunities to improve your work.

And as soon as I see it that way, I’m okay with Elisabeth’s ideas. I may debate a few points with her. I may even win a few. But I get it. She wants the best work. We’re on the same team. Unbounded isn’t mine alone anymore.

Which is actually pretty cool.

So I guess it’s time to take another slice at the script, make it bleed ink.

Write on, all!

Writing a script to exact page specs (120 to be exact) forces me to be brutal about edits.

That 8 page sequence? It needs to be 4. That 2 page scene? It needs to be half a page at most. Scripts have even less excess description than novels, but there is still excess.

I find myself stripping everything down to the bare communicability. “What is the minimum I need for the reader to understand what I’m trying to communicate?”

The art of writing is not in how many beautiful words you can use to describe something, it’s how few words you can get away with and still have something that makes sense to the reader.

Adapt one of your novels to screenplay. I dare you. You will feel like editors are treating you with kid gloves. :)

I’ll never look at novels the same again. The excess space they give you to iterate and re-iterate, describe, and have characters reflect and pontificate is nothing less than sheer luxury.

Adapt one of your novels to screenplay. I dare you. You will feel like editors are treating you with kid gloves.

Ooh, a challenge?! But you already know I’m serious about trying it. I even purchased the Final Draft V7 software, and I have scads of screenwriting books. First the editing of this beast though.

There are so many different kinds of writers, though at the heart of every good story is just that: a good story. Strip out the pretty words and see if it stands strong on its own, if you’ve created something memorable. But I’d like to keep some of my pretty words, too, because writing a novel-length manuscript does offer that luxury…and I’d like to bask in that a little. ;-)

Therese,

I’ve come to think of it like this; When you write a screenplay, someone else is the director, the cinematographer, the set designer, etc. When you write a novel, you are all of those things in addition to being the writer.

For me the difference between writing a script and a novel is whether someone else will do those things for you or not, and what that allows you to sacrifice in the writing.

I find from doing novels first I have a tendency to over-direct in a script. “The character goes here, does this, has this look on their face.” Along with lots of parentheticals on my dialogue tags.

Richard

(frowning)

Did you see my wallet?

That kind of thing. It takes a bit of re-training to stop being the director. :)

I think when I go back to novels though, I’ll be a better novelist. More concise, to the point, and visual/action oriented.

It’s an interesting enough experience that I’d say all writers could benefit from the cross-training.

I agree with you about the cross-training. And I’ve long since been a fan of script reading. Shakespeare in Love, Being John Malkovich (brilliant), Ghost and Four Weddings and a Funeral all sit on my shelf for various reasons.

Thanks for the heads up about the parentheticals. I can easily see myself providing way too much information!

What I think would be hard would be to take a mostly internal novel, like Atonement or Ordinary People, and then make it a compelling screenplay. But obviously it’s been done!

One of the tricks I learned from Jane Espenson (https://www.janeespenson.com) for the internalizing stuff is to have characters focus on a object representative of that internalization.

Say a woman is depressed over her dead husband, have her stare at a photo of him. Or if an object in the present reminds of an object in the past, have the focus on that object lead into a flashback, etc.

In other words, use physical objects, props, etc. that have some kind of emotional significance to externalize internal feelings.

Maybe you guys could interview Jane? :)

Many of those tricks can be used to great effect in fiction writing too, as another way to avoid the Lifetime-Movie-of-the-Week melodramas.

We’re going to have to make a new Interviews push pretty soon, so I’ll add Jane to the list.

Teri,

I know the blood, sweat, tears, and toil it took for you to get to this point. I’m extremely happy for you. Revise, revise, revise–you’ll feel great when it’s on the printed page and you’re spending that advance.

Thanks, Richard!

It’s sad when a writer has to become a serial killer. I don’t know if it ever gets easier. “I surrendered the phrase, but not happily.”

After editing so much, at this point I guess it’s better to let someone else tell you what to edit out. It sorta eases the guilt over the murdering, doesn’t it? And the sick feeling that you’re killing a line that will make the whole story collapse. Because if the editor doesn’t want it there, then you can’t be blamed, right? Right?

Hang in with the edits, I know you’ll do great!