AUTHOR INTERVIEW: Rosina Lippi/Sara Donati

By Kathleen Bolton | October 5, 2007 |

Novelist Rosina Lippi followed her heart and it led to critical and commercial success for her books. A tenured professor of linguistics at the University of Michigan, she did what many of us aspiring novelists do–write fiction in the corners not filled by job and family. Her novels eventually enabled her to leave academia to pursue a successful career as a full-time novelist.

Novelist Rosina Lippi followed her heart and it led to critical and commercial success for her books. A tenured professor of linguistics at the University of Michigan, she did what many of us aspiring novelists do–write fiction in the corners not filled by job and family. Her novels eventually enabled her to leave academia to pursue a successful career as a full-time novelist.

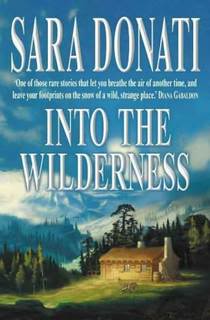

Her debut novel Homestead won the PEN/Hemingway award in 1999 and was short listed for the Orange Prize in 2001. But it was Into the Wilderness, a re-imagining of James Fenimore Cooper’s novel The Pioneers which brought her widespread commercial success. Written under her pen name Sara Donati, the Wilderness series has generated a highly successful series of historical novels and garnered legions of devoted fans.

But Lippi isn’t content to rest on her Wilderness laurels. She’s also made forays into contemporary women’s fiction. Tied to the Tracks, her first effort, is set in decidedly 21st century Georgia. In February, 2007, a second contemporary, The Pajama Girls of Lambert Square, releases. Currently, she’s at work on her sixth title for the Wilderness series.

We are pleased to present our interview with Rosina Lippi.

Q: You left academia to pursue writing fiction. Can you fill in the story of that journey for us? Do you think academia prepared you for writing novels, or did academia drive you into it?

RL: It was really a gradual process. I was more and more involved in writing fiction, and less and less enamored of academic politics. So I suppose you could say that academics drove me to write fiction, but my guess is that I would have ended up here anyway. Assuming the same good fortune that has allowed me to actually earn a living writing.

Q: It’s mind-boggling to note that you write enormous historicals under the name Sara Donati and contemporary literary fiction as Rosina Lippi (nine books in as many years). I’ve got to ask where you find the time, energy and inspiration to write so quickly. Could you share with us your daily writing routine, and how to you keep your energy level up?

RL: In the interest of full disclosure — it’s been longer than nine years. I started writing seriously about 1993.

It’s an odd thing, I get asked this question all the time and it always takes me by surprise. I think I write really slowly; it certainly feels that way. But an effort to try to answer your question in spirit rather than letter: I’m usually busy and focused on something because well, obsessive compulsive runs in the family.

Q: You’ve been able to carve distinctive voices for the two different genres you write, contemporary and historical. Historicals in particular are tricky because it’s easy to let an anachronisms slip in. Do you find it difficult to switch back and forth between the eras, especially with dialogue?

RL: I’ve been writing the Wilderness novels for so long that it isn’t very hard to get back into the setting. These are characters I know really well, and they are very talkative and even opinionated. There’s something going on now that Elizabeth thinks is a very bad idea. As far as the contemporary novels are concerned, there’s a long preparation stage where I spend a lot of time with the characters and the setting. If linguistic field work has been done in the right place at the right time, I read that. I also listen to music, radio if I can get it, and recordings of local comedians. For example, writing about the deep south, I listened to recordings of Andy Giffith and other dyed in the wool southerners, just to get the rhythms working in my head. You’d probably guess that matters of dialogue and language are really interesting — and important to me. That follows naturally from my academic training.

Q: Historicals are demanding and yours are richly detailed, exploring how races and class boundaries collide in late 18th century/early 19th century New York State. What’s your research process, and how do you determine when enough is enough, and what’s your rule of thumb for giving the reader the feel of the period without resorting to the dreaded info dump?

RL: It depends on the where/when. If the historical record is there, I do what I can to get hold of original sources. For example, I hired a graduate student in American history to go dig through the Manhattan municipal archives and make copies of a wide variety of meeting notes in the period 1800-1805. I needed to reconstruct the whole early history of smallpox vaccinations because — believe it or not — there was no record. Not in medical journals or histories, nowhere. I finally got my hands on a copy of the handwritten manual put together by Dr. Valentine Seaman (I’m not making that name up) explaining how the vaccinations were to be carried out, what the different stages were, etc etc. Even then I still didn’t know how they moved the vaccine from one place to another, so I had to make some logical jumps. The Almshouse in Manhattan at that time was such an interesting place, I ended up writing more about it than I had originally planned, but I believe it all furthered the story. This is Lake in the Clouds I’m talking about, by the way.

I have to put just as much — if not more — research into a variety of other subjects that don’t necessarily interest me. When my characters had to sail from Canada to Scotland, I learned more about ships and sailing than I ever wanted to know. All this applies to contemporary novels, too. The big challenge is to be honest with myself about any given scene. Does it move the story along or is it me showing off what I learned reading all those old newspapers? Often I have to put a scene away because it would be too much, but sometimes I’ve been able to find a different home for those orphans. By far the most rewarding source of good historical detail that won’t overwhelm the reader: footnotes. In history texts especially. That’s where the academic puts things that are interesting, but not necessarily of direct relevance to whatever point s/he was making.

Q: The Wilderness books are often described as a sequel to the Last of the Mohicans, where one of the main protagonists is the son of Hawkeye. Was that a scary decision to pursue that angle and did you worry about the reaction from James Fenimore Cooper purists?

RL: I never called Into the Wilderness a sequel; a reviewer did that, and I’ve never been able to shake it. Into the Wilderness is a retelling of Cooper’s The Pioneers. I kept some of the story line, some of the characters, some of the themes. It may surprise people to know that Cooper was already writing about conservation of natural resources, but he was. In fact, when I’m accused of anachronisms, it’s most usually about things that can be documented. Thus the old chestnut: fact is stranger than fiction. As far as purists are concerned, I actually understand their misgivings. Not every story is for every reader.

RL: I never called Into the Wilderness a sequel; a reviewer did that, and I’ve never been able to shake it. Into the Wilderness is a retelling of Cooper’s The Pioneers. I kept some of the story line, some of the characters, some of the themes. It may surprise people to know that Cooper was already writing about conservation of natural resources, but he was. In fact, when I’m accused of anachronisms, it’s most usually about things that can be documented. Thus the old chestnut: fact is stranger than fiction. As far as purists are concerned, I actually understand their misgivings. Not every story is for every reader.

Q: You are known for peopling your books with a rich array of characters, keeping each memorable and anything but stereotypical. How do you develop distinctive characters and what should writers be mindful of when creating their own? Do you feel pressured to have all of them make an appearance, however slight, in each book?

RL: Oh gosh no. If I tried to get everybody into this Wilderness book I’m working on I’d never finish it. I tend to focus on one or more subset of major characters per book. Lily’s story was told in Fire Along the Sky, for example. As far as making secondary or even tertiary characters memorable, I have to say that I learned to watch for this from Dickens. He was such a master at drawing a personality with a sentence or two, it made a huge impression on me. I pay a lot of attention to this as a result.

Q: Your books are densely woven with multiple plot threads that sometimes don’t get resolved until a few books later. Do you plot extensively in advance, or let it unfold organically? Have you ever been so unhappy with a scene or a plot thread that you’ve chucked it and started over?

RL: I do plot, but not in detail. When I start I have a sense of the major characters, the major conflicts, and some of the scenes. Usually also some idea of where and how this particular book will close. Many, many times I’ve been surprised by a character who pops back into the story when I thought we had parted ways. A minor character suddenly intrudes and takes on a much bigger role than first imagined. I have also been taken completely by surprise when my subconscious presented me with a plot twist that I didn’t see coming. I’m working on book six in the series now, and I have had several false starts and scenes I had to put aside. This novel has been harder than the others.

Q: Can you tell us what it is about this particular book that’s been challenging for you?

RL: I’m not really sure, except it’s the last one in the series and I have many threads to weave into the whole, lots of things to resolve, and 1.2 million characters. Okay, so it just feels that way.

Or maybe I’m just getting old.

Click the link below for part two of our interview with Rosina Lippi.

what a wonderful interview! Ms. Lippi sounds as interesting as her books! thanks, WU

I love Rosina’s style. Her characters are witty and sharp. Thanks for doing this interview, WU! Looking forward to part two.

What a great interview, I’m looking forward to Part Deux. I love Rosina’s style and the whole interview was warm and informative.

She’s incredibly warm and her responses were insightful. Part two is even better.

I am anxiously awaiting Ms. Donati’s sixth book. I have re-read the first five in anticipation !! I read Ms. Donati’s book as I KNOW the historical facts are true!! And that makes the story so much more interesting!!!