INTERVIEW: Dale Launer, Part 2

By Therese Walsh | June 8, 2007 | Comments Off on INTERVIEW: Dale Launer, Part 2

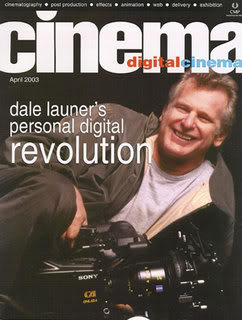

Congratulations to Dale Launer, whose latest film, Tom’s Nu Heaven, just won Best New Film at the Monaco Film Festival! Launer talks about TNH in this part of his interview with WU, but here’s something he didn’t mention: that he filmed this movie himself using a Sony digital high-definition HDW-F900 camera. (Sounds daunting, doesn’t it?)

Congratulations to Dale Launer, whose latest film, Tom’s Nu Heaven, just won Best New Film at the Monaco Film Festival! Launer talks about TNH in this part of his interview with WU, but here’s something he didn’t mention: that he filmed this movie himself using a Sony digital high-definition HDW-F900 camera. (Sounds daunting, doesn’t it?)

If you missed part 1 of WU’s interview with Dale Launer, click HERE then come on back. In this, the second of three parts, Dale talks about faultless characters, how he put his mark on Dirty Rotten Scoundrels, how the film industry has changed…and how it needs to change. Enjoy!

Part 2: Interview with Dale Launer

Q: You recently wrote and directed the independent film, Tom’s Nu Heaven. Was the film everything you’d hoped for?

DL: No, they never are. It’s hard to be objective. I hate all my films. But if I’m watching them with an audience and they laugh and applaud – I figure something must’ve worked. I did a screening of Tom’s NU Heaven last year. Everything that could go wrong did go wrong. The sound was off, not loud enough, the bass was way too high, the image was faded looking, it skipped frames (wrong frame rate for this projector), it stopped, it lost sync, the movie stopped a number of time, even for 20 minutes a little over an hour into the movie. Horrible experience. But what I learned? If people are enjoying your movie you can turn a firehose on them and they’ll just move out of the stream to watch the movie. It was, oddly enough, a very successful screening.

Q: How about the experience of being the director – will you continue wearing both hats?

DL: No problem there. I actually got into this business to be a director. But I quickly learned that writing the real creative part of movies, directing is creativity in the margins – at best an interpretive art. Most of it is management and the ability to wake up early in the morning and stay awake all day. As far as talent is concerned, casting well and having the taste to pick a good script will catapult you to becoming an “A” list director. And keep you there.

Q: I think there’s something inherently funny about competing antiheroes, as in Dirty Rotten Scoundrels—a suave, high-rolling confidence player vs. a gauche, unrefined one. Viewers are left to sit and watch without bias, waiting with anticipation to see how the lies and deceptions will play out and who’ll reign victorious. I’m wondering if you feel a certain freedom writing the antihero’s story: no real audience expectations, all bets off. Does this make comic writing easier?

DL: First of all – Scoundrels is a re-make. The story and characters were already created and the best parts of the story was already written. I could have changed it (to “make it mine”) but I thought why fix it if it ain’t broke? So I fixed what I thought could be improved (cutting almost 30 pages out of the beginning – all Freddy’s stuff.) And the end, where the mark – the woman they were competing for – turns out to be a con artist (she wasn’t in the original) and takes them both. Actually, I had it slightly different in the script – the Lawrence Jamison character knows it all along, but you don’t know that until the very end. And he’s fallen in love with her. You think he’s fallen in love with her because she’s so guileless, so honest, so decent – and then she take him – and you feel bad for him. But, in the end, you find out he did fall in love with her, but not because of her guilelessness, but because she was such a good con artist. I think the director and editor saw that it could work either way, so they changed it. Maybe it’s better, but it’s an editing change. It’s not much different actually.

So, anti-hero? Hm. I remember hearing the term back in the late ’60’s or early ’70’s. I’m not conscious of writing anti-heroes. I wrote a script called BAD DOG, but the protagonist is aggressive, ambitious, but still charming. Maybe he’s an anti-hero. Okay, here’s your answer – a hero who has no faults probably doesn’t have much of a personality. Your characters have to have something about them, something about their personality, that influences the decisions they make. If you don’t, he/they/she won’t be fully integrated into the story. They make choices that determine the direction of the script.

Q: How long does it usually take you to move from concept to finished script?

DL: From the idea to a finished script? A few months to a few years. When I was younger I could sit down and start writing and have a first draft in a month. (that doesn’t include the concept and compiling notes, which can take months to years, but that isn’t full time work). Now it takes longer – and it’s hard to say.

Q: When do you know a script is finished?

DL: When it’s released!

Q: What are you working on now, if you can say?

DL: Three projects. I’d rather not say. Sometimes movies don’t get made right away, and your scripts get handed around, copied, and picked clean. I see stuff from scripts I wrote show up in other movies.

Q: Do you think the requisites for a solid screenplay have changed over the last decade or so? How? How has comedy changed, and how have these changes (if this applies) affected screenwriters?

DL: I see good movies come and go. And bad movies become hits. But that has always been the case. As long as they make money, they get financing and find their way into theatres. Right now there’s a kind of broad, somewhat black comedy that’s been popular. Broad comedies come and go, but these are a little darker than they used to be. Some might call it “edgy.”

Q: A few years back you gave a great speech about auteur theory at the National Association of Broadcasters conference. I find it fascinating that you were a fan of auteur theory even when you were in school to become a screenwriter. Why do you think that is?

DL: When people started taking movies seriously they started writing about it seriously. Le Cahiers du Cinema (french movie magazine started in the early ’50’s) was really the first to take movies seriously. As a result their theory became the only reference in existence. And it became the tools that teachers used and taught. And other critics caught on to it too. But I learned my first student film that no matter how brilliant you are at directing, if your script sucks, your movie sucks. There is a primacy there which has yet to come to light in the movie business. TV – with its gigantic appetite for content, has pushed aside the star theory, pushed aside big producers, and now it’s the head writer/show runner is the most powerful. And makes the best material. Funny, but directors are treated respectfully in TV, but they don’t have anywhere near the power they have in movies. TV pretty much treats directors the way the old studio system did.

Q: Do you think anything will ever change in Hollywood regarding the level of acclaim the director gets as opposed to the writer? Why or why not?

DL: Yes. It’s evolutionary. Truth eventually fights its way to the forefront. They’ll continue making mistakes until they get it right. Unfortunately it will probably be in another 30 or 40 years.

One thing is going on right now – the “digital revolution” – where anybody can afford a camera that will allow them to shoot movies. What will happen is that we’ll be seeing thousands of features – and none will get a release. They’ll end up on the Internet in one form or another and by and large, almost all of them will be terrible. But that 1% (maybe less) will be very interesting. 5% will be okay. The rest will vary in awfulness. But what people will learn, eventually, is that you can’t make a good movie out of a bad script. So this will bring along a new appreciation of (good) writing.

Come back next week for the third and final part of our interview with screenwriter Dale Launer!