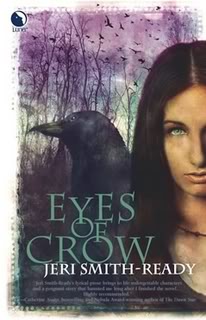

INTERVIEW: Jeri Smith-Ready, Part 2

By Therese Walsh | April 6, 2007 | Comments Off on INTERVIEW: Jeri Smith-Ready, Part 2

Jeri Smith-Ready has not only been busy writing her highly acclaimed Aspect of Crow series, she’s been busy selling new ones. Pocket Books (a division of Simon & Schuster) recently purchased her funny urban fantasy vampire series, about a bunch of vampire DJs. The first book, Bad Company, will be released next year, followed shortly after by its sequel, Bad to the Bone.

Jeri Smith-Ready has not only been busy writing her highly acclaimed Aspect of Crow series, she’s been busy selling new ones. Pocket Books (a division of Simon & Schuster) recently purchased her funny urban fantasy vampire series, about a bunch of vampire DJs. The first book, Bad Company, will be released next year, followed shortly after by its sequel, Bad to the Bone.

If you missed part one of our interview with Jeri Smith-Ready, you can catch up by reading it HERE. In this segment, we’ll chat about trilogies, world building, the importance of character, and why it’s not always a good thing to overanalyze the muse.

Part 2: Interview with Jeri Smith-Ready

Q: What sorts of issues do you take into account when planning a trilogy, as you are with Eyes of Crow?

JSR: I often wish that I could have written all three books before having any of them published, so that I could go back and plant little details. It’s impossible to know what issues and “gifts” are going to pop up until you write the actual books. But you have to obey the rules of the magic system established earlier. It can be incredibly annoying–I mean, it presents a unique challenge.

Each installment of a trilogy, in my opinion, should have its own story and theme, while reinforcing the trilogy’s broader theme and story arc. The overarching theme of the Aspect of Crow series is the relationship between humans and the natural world. The main story arc is the confrontation between Rhia’s people and the Descendants, who each embody the two main ways we can relate to the natural world–as partners or conquerors.

Also, each piece of the trilogy focuses on one phase of Rhia’s life–coming of age, early adulthood (when she learns to take responsibility for more than herself), and finally maturity. Each phase conveniently corresponds to a phase of her magic.

Yet each installment offers something radically different than its predecessor. Voice of Crow gives us four different viewpoints and several new settings. Wings of Crow takes place a generation later, giving the readers a shakeup right from the beginning. Mostly I think this was to keep me from getting bored. With each new book, I like to give myself a high mountain to climb, then see how I handle the lack of oxygen.

Q: What steps did you take to massage your initial idea for Eyes of Crow? How did this world become real for you?

JSR: To me it’s not so different from our world. There are no magical creatures or wizards or elves. The characters are just like you and me in many ways–they struggle with love, family, and issues of identity and destiny. The only differences are that they commune directly with Spirits, and they lack much of what we would consider technology.

Q: The Crow world also reminds me of native cultures, with wise men and women, and others who embrace their animal aspects. Did you study American Indian society when you built your world?

JSR: Though Eyes of Crow has been interpreted as Native American-inspired, I created the world from scratch, and it has nothing whatsoever to do with American Indian culture.

To explain, a not-so-secret secret: Eyes of Crow takes place several thousand years from now. It all began with the mid-21st-century Collapse and Reawakening, when the Spirits called certain people to follow them and build a new way of life. It’s sort of like The Rapture, but more life- and earth-positive–the chosen people get to stay here and survive rather than be taken away. I wrote a serial short story about the Collapse and Reawakening for my publisher’s website entitled “The Wild’s Call.” (Read it HERE.)

The basic concept of the animal spirit comes from a spiritual practice called “core shamanism” or “neo-shamanism,” a term coined by anthropologist Michael Harner. In the 1950s and 60s, Harner lived with several tribes in different areas of the world, and he noticed that they had certain elements of spiritual practice in common. The idea of the Power Animal, a helping spirit that embodies certain qualities of the shaman, is one of those elements.

In core shamanism, few are called to be actual shamans (just like few people can be doctors), but anyone can be a “shamanic practitioner.” We each have a Power Animal who guides us and helps us. It’s like having a patron saint.

So I took this concept of the Power Animal to its magical extreme and made up the rest. My intention is not to portray shamanism as fantasy, because to a lot of people, including myself, it’s real.

The one thing I did borrow from Native American culture was the legend of Raven bringing light to the world, which comes from the Haida and Tlingit tribes of the Pacific Northwest. I changed Raven from male to female and made Her the Über-Spirit.

I strongly believe that no culture or ethnicity has a monopoly on embracing the natural world. It’s a learned response that can be enhanced or stifled in anyone. In most of us in Western society, the impulse has been downright smothered, but it’s never too late.

Q: How important do you feel world-building is in a fantasy-type novel in general? More, as or less important than character-building? Why?

JSR: Nothing is as important as character. World-building without fully fleshed characters just becomes so much window-dressing. I’m less interested in ideas than people.

However, when you create an original world, everything must be consistent and justified. Why do your people have a particular political system? What do they eat and where do they grow or hunt it? It requires research into so many things we 21st-century people take for granted–agriculture, ecology, economics.

In a way, I had to create two worlds for Eyes of Crow, the disparate villages of Asermos and Kalindos. What would possess the Kalindons to live in such a harsh environment, and how would they ensure their survival? How would their environment alter their people’s character? In Voice of Crow, we also see the village of Velekos and, even more foreign (to Rhia, at least), the city of the Descendants.

Q: Which came first: the William Butler Yeats poem “The Two Trees” or your concept for the two trees (representing two very different choices for Rhia–a hollow, safe life or a passion-and-pained filled one)? How important was this concept for you as the story developed?

JSR: I got the idea from the poem, to which I was introduced through Loreena McKennitt’s haunting musical rendition. The interpretation I’ve heard (and applied here) is that the barren tree represents cynicism and detachment from life’s heartaches, or as Crow says, succumbing to the belief that death makes life bitter rather than sweet. The living tree is an embrace of life in all its joy and pain–in fact, holding onto joy even in the face of pain, even when despair seems like the only rational response.

On a personal note, that song was my “birthday song” (the first song I hear after 10:15AM on my birthday) in 2004. The choice of detachment versus engagement was a powerful one during an election year. I chose engagement, working hard for the side that ultimately lost. My heart was broken, but that’s always the risk when we fight for something we believe in.

The more we care about something or someone, the greater the chance we’ll be hurt. But the lesson of the two trees is that to stop caring only deadens us. It’s a battle doctors and other caregivers face every day–too much compassion and empathy harms their ability to work, but too little is even worse.

So Rhia, whose lot is to help the dead and dying and their loved ones, is tempted to shut herself off from the pain involved. Her mentor Coranna would prefer Rhia to be more detached, but that’s just not in Rhia’s personality. Learning to accept her emotionalism as a strength and not a weakness is part of her journey.

Q: You had to essentially create Death to write this book. Was this a challenge for you? Why or why not?

JSR: The scenes on the Other Side were the last ones I wrote, because I found the idea intimidating. But once I opened my mind, they ended up not being difficult. I enjoy the head-trippy stuff, though I have to be in a certain mood to write it. Listening to Dark Side of the Moon helps. Things get even more psychedelic in Voice of Crow.

I should add that trippy for trippy’s sake will only make a reader go “huh?” Each wild-ass image should have a purpose beyond the “duuuuude” factor. It should represent a character or story aspect that a reasonably intelligent reader can interpret. Don’t just reproduce your dreams or hallucinations on the page. They’re not as interesting as you think.

Q: Many of your scenes take place in unique settings. (You don’t fall into the characters-chatting-in-the-kitchen trap at all!) The transforming forest, the cleansing pond, the white world of death—they’re all settings that amp up the tension in the scene by forcing the character to face something. The tree houses are interesting, too, forcing Rhia to look at things from a new perspective. Do you give a lot of thought to where each scene is best set and the layers of meaning each setting might convey to the reader?

JSR: After a lot of thought and wishing for a profound response, my answer would have to be, “Not really.” It must be instinctive. The more I try to examine it, the more elusive it becomes. Maybe it’s one of those “muse gifts” that wither under the harsh light of analysis.

Come back next week for the third and final part of our interview with Jeri Smith-Ready!