AUTHOR INTERVIEW: Sarah Monette, Part One

By Kathleen Bolton | February 23, 2007 |

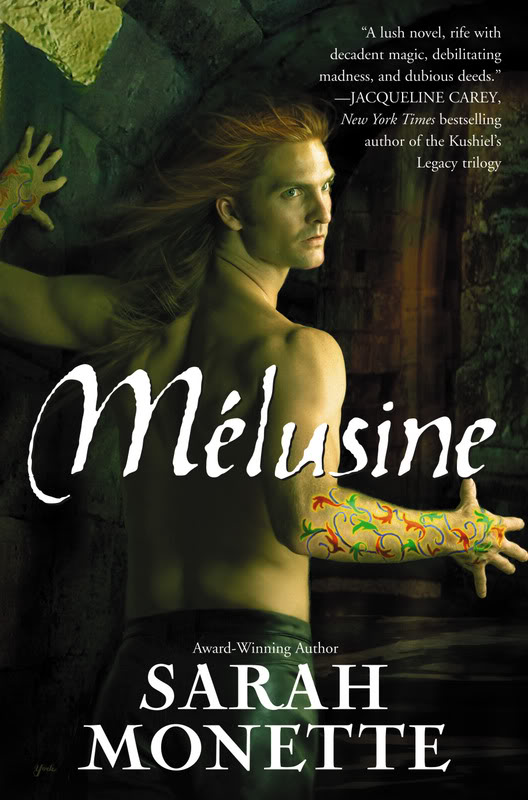

A powerful wizard endures a terrible rape; a catburgler robs the wrong person and is set on a dark path; both are fated to be bound by violence and blood ties. And this was just the first 100 pages of Sarah Monette’s stunning fantasy debut novel MELUSINE. I lost a weekend to Monette’s intricately plotted and multilayered story, woven together with delicious prose. Monette’s follow up effort, THE VIRTU, was just as compelling. With characters whose complicated sexualities add an element of the decadent, and whose motives are never what they seem on the surface, Monette has created a dark world that evokes claustrophobic, historically dense Old World metropolises. And then there’s the magic.

A powerful wizard endures a terrible rape; a catburgler robs the wrong person and is set on a dark path; both are fated to be bound by violence and blood ties. And this was just the first 100 pages of Sarah Monette’s stunning fantasy debut novel MELUSINE. I lost a weekend to Monette’s intricately plotted and multilayered story, woven together with delicious prose. Monette’s follow up effort, THE VIRTU, was just as compelling. With characters whose complicated sexualities add an element of the decadent, and whose motives are never what they seem on the surface, Monette has created a dark world that evokes claustrophobic, historically dense Old World metropolises. And then there’s the magic.

We are very pleased to bring you our interview with Sarah.

Q: Tell us about your journey to publication

SM: About the usual, I suppose. I started writing as a teenager, kept writing through college and grad school, found an agent, and he did the rest. I got my first book deal the week before my doctoral dissertation defense, and that seemed like a sufficiently unambiguous sign.

Q: What drew you to the fantasy genre?

SM: Most great children’s literature is either fantasy (THE HOBBIT, the Chronicles of Narnia, THE WIND IN THE WILLOWS) or might as well be fantasy for a modern child (A LITTLE PRINCESS, LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE, TREASURE ISLAND). The books I loved as a child were the ones in which things were different, in which there were puzzles and mysteries to figure out (I also loved Encyclopedia Brown). That’s still true. I read a lot of nonfiction these days as well as fantasy, science fiction, and horror, but my comfort reading is mysteries. So I can’t talk about being “drawn” to fantasy; I’ve been rooted there for as long as I can remember.

Q: Where did the inspiration for your Doctrine of Labyrinths series begin?

SM: At this point, it’s really difficult for me to remember, since I started writing these books in 1993. I have a fairly clear memory of walking back from class to my dorm, with this voice in my head saying I slammed the door behind me (see MELUSINE, p. 14), and I was trying to work out who this person was and what he was fighting with his lover about and how this was the first domino leading to the absolute ruin of his life. Even at that point, the Mirador was a citadel, although the city of Melusine came later. (The city was in fact one of the last parts of the world to get a name.) And I remember that what drew me to this particular voice and this particular story was the tension in the character between being the victim and being the predator, the shifting power dynamics.

But other than that, I can’t reconstruct it. I worked on the story arc of MELUSINE and THE VIRTU slowly and haphazardly for years, and it accreted things from what I was reading and what I was studying and what I was thinking about. And I had no idea where the story was going when I started it (unlike the arc of THE MIRADOR and SUMMERDOWN, where I knew how it ended before I knew how it began).

Q: The books are intricately plotted and intertwined. Do you plot extensively in advance, or do you tend to fly-in-the-mist?

SM: I am very much of the make-it-up-as-you-go-along school. Even in books, like THE MIRADOR, where I know where I’m going, I find out how to get there by writing it, not by outlining. This leads to a lot of revision and rewriting and complaining to friends.

I also tend to write with a lot of flourishes and tangents and apparent digressions. When I turned in MELUSINE, my editor asked me if I really needed the scene with the ghosts and the labyrinth in Nera. I was sure I did, and insisted on keeping it, but I didn’t know why until near the end of THE VIRTU, when it turned out to be the key to solving a very difficult problem that I hadn’t even known about when I wrote Nera to begin with.

Lewis Carroll’s White Queen says it’s a poor sort of memory that only works backwards, and I think my subconscious agrees with her.

Q: Can you tell us a little bit about your revision process? Has the way you revise changed now that you have to meet publishers deadlines?

SM: Well, I’m trying to get more of the story right as I go–hopefully applying everything I’ve learned in writing MELUSINE, THE VIRTU, and THE MIRADOR.

As it happens, with all three of those books, I had a complete draft BEFORE I sold them. So this is really new territory for me. We’ll see how it works out.

Q: The SF/F genre relies heavily on authentic world-building. What is your approach to creating a realistic world that readers can lose themselves in?

SM: I pay a lot of attention to popular culture: what card games are people playing, what stories are they telling, do they go to plays, to operas, to pantomimes? What are they reading? I’m also mindful of history, especially the history of the buildings the characters live in.

I have a personal fascination with names and languages, and I use that. Also, I love trivia–as for example, if you go to Vienna, there’s a museum where they have the car in which the Archduke Franz Ferdinand was shot, bullet holes and all (thus starting World War I). Also the uniform he was wearing. Bullet holes and all. I try to come up with things like that for my invented worlds, to create a kind of depth of weirdness rather than just saying, Look! Magic!

And I try to think things through, to figure out the consequences of the world-building decisions I make and not just leave them floating.

Q: One of the things that knocked my socks off was the way you maintain and build tension in each scene. What’s your secret to creating a nail-biting scene?

SM: I wish I had a good, clever, pithy answer for you, but I don’t. The best I can do is to say that I try to make sure each scene I write is doing a lot of work, that something changes between the beginning and the end. I also do my best to write plots in which the external action and the internal emotions are intertwined, so that the characters care about what they’re doing on as many levels as possible.

Q: Your books explore the terrain of sibling rivalry and love. Why did you choose to write a story like that?

Q: Your books explore the terrain of sibling rivalry and love. Why did you choose to write a story like that?

SM: The honest answer is: I didn’t. To begin with, I had Felix and his world falling to pieces, and I got to the point (it’s Chapter 7 of MELUSINE now) where they’re fleeing the city and everything’s gone to hell in a handbasket, and I had no idea what happened next. No idea how to solve the problems I’d thrown at my poor protagonist, no idea what to do. I was in college, so I left the story and did other things, and came back periodically and read what I’d written, and I still didn’t know what to do.

I had another character taking up space in my head: the semi-literate, incredibly talented thief who’d like to go straight but can’t. In desperation, I dropped him into the city and gave him a client with a problem (very Chandleresque, really), writing, of course, towards letting him meet up with Felix as a kind of very elaborate deus ex machina, since he wasn’t crazy and wasn’t being scapegoated by his former colleagues and could therefore think outside the box.

But as I prodded Mildmay toward this meeting with Felix, it became apparent that I’d written myself a tremendous problem in the course of trying to solve this other tremendous problem: Mildmay, who hated and distrusted wizards, had *absolutely no reason* to care about Felix. So I could get him to this meeting I needed, but he had no reason to do anything about the terrible log jam of my plot.

So I made them brothers. And let Mildmay be the sort of person for whom that would matter.

And then they were stuck with each other, and I was stuck with them being stuck with each other, and since I’m a heavily character-driven writer, exploring that relationship became central to the engine of the next three and a half books.

Q: Every writer out there is nodding and identifying with this dilemma. How do you deal with writer’s block? Do you ponder, or do you try to write yourself out of the block?

SM: I read a book by Victoria Nelson, ON WRITER’S BLOCK, that was incredibly helpful in terms of conceptualizing what writer’s block is. And what it isn’t. It’s not the end of the world. It’s not a major trauma. It’s a sign that I haven’t asked the right question.

A friend says that when she gets stuck, she writes about why she’s stuck, or what she’d be writing if she weren’t stuck, and I’ve found both of those tricks very useful, too.

Click here for Part Two of our interview with Sarah Monette.

a lot of wise advice here for writers. great interview. look forward to part 2

“I find out how to get there by writing it…”

This was a super-interesting interview. Looking forward to part two!