INTERVIEW: Juliet Marillier, Part 3

By Therese Walsh | November 3, 2006 |

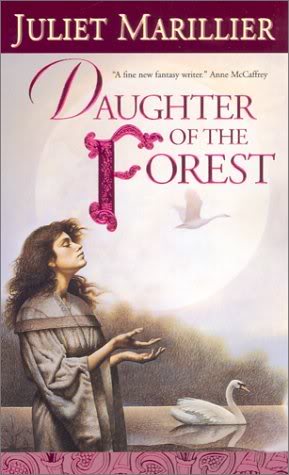

If you missed parts one and two of our interview with Juliet Marillier, you can read them by clicking HERE and HERE. In this third and final segment, we’ll learn more about making story choices, building and keeping control of strong characters, and all about Marillier’s hit novel Daughter of the Forest. We’ll also learn about her personal influences, her favorite books and the best writerly advice she’s ever received.

If you missed parts one and two of our interview with Juliet Marillier, you can read them by clicking HERE and HERE. In this third and final segment, we’ll learn more about making story choices, building and keeping control of strong characters, and all about Marillier’s hit novel Daughter of the Forest. We’ll also learn about her personal influences, her favorite books and the best writerly advice she’s ever received.

Part 3: Interview with Juliet Marillier

Q:There are so many choices to be made throughout your books. Who lives and dies, who is chosen for mate and who is disappointed, who completes their journey and who is left wanting… Do you ever decide on an ending that wasn’t your original conception, or do you guide everything purposefully from the start? Are you ever surprised while writing?

JM: Thus far I’ve never written an ending that is different from the one I planned, but I do sometimes deviate from the book’s plan in the middle. Characters often become interesting as I write and assume more major roles in the story than I intended. Simon in Daughter of the Forest was one of these and Deord in Blade of Fortriu was another. Deord was based on my son’s martial arts teacher. He started out as just a physical description, and the character that developed around that was one I grew to like very much. As a result, his back-story plays a significant part in the next novel, The Well of Shades – not something I intended, but it works.

I do prefer to keep control of my plot, so I don’t often get surprised. Sometimes I feel a push to do something different, such as preserve a character who has to die, and when that happens I make a choice based on what works best as part of the overall storytelling. Usually the plan wins out. In Blade of Fortriu the resolution of the love triangle had me thinking hard, with a definite pull to make it work out differently, but I could see that was impossible for the characters in the time and culture of the story.

Q: Foxmask’s Thorvald is driven by one-channel intellect, Sam by emotional allegiance, Creidhe by practicality, Keeper by oath-bound integrity and Somerled by fear. How do you build character for the best plot when creating such complex stories?

JM: By making my characters true to their heredity and upbringing, as well as allowing them to transcend those if they have the strength or the need to. By having them respond to challenges in a way that is consistent with that principle (and, where needed, creating challenges that will allow characters to have revelations, to grow and learn.) By seeing them as real individuals from the start.

I don’t see Somerled as motivated by fear – unless it is his deep-seated fear of being alone, or his fear of his own potential.

Questions about Daughter of the Forest:

Q: Was Daughter of the Forest your first book? Did you have other books written and “sitting in wait” or did you have other ideas brewing?

JM: I have one complete short fantasy novel, written before Daughter of the Forest, sitting in a drawer. It has heaps of flaws so it’s unlikely ever to see the light of day – it was never submitted to a publisher. I was just cutting my teeth as a novelist when I wrote it. I did attempt at one stage to write category romance but was not very good at it. I would consider Daughter of the Forest my first ‘proper’ book. I didn’t start writing fiction seriously until after a substantial working life in other fields. Making the fairytale of The Six Swans into a novel was something my heart told me it was time to do at that point in my life. Daughter of the Forest wasn’t written with any particular expectation of publication, more for personal satisfaction.

Q: How long did it take you to write Daughter of the Forest? And when did you first think, “Hmm, maybe this is something I can and should try to get published?”

JM: I worked on Daughter of the Forest for three years, but that was very much part time. I had a full time day job as a public servant and was a single parent with two school-aged children, so writing time was limited. The ‘Hmm’ moment came after I had finished the manuscript. It was more of a ‘Oh, well, I may as well submit this to someone, there’s nothing to lose’ moment. I was far too paranoid to show it to family members or friends.

Q: Daughter of the Forest was written in first person. What were the advantages and disadvantages to working in this narrative? Why did you choose it then and would you do it again?

JM: The biggest advantage for me was the way it allowed me to get under the protagonist’s skin, to be her for the period of writing, and thereby to bring readers right into the heart of the story. So many people have written to tell me they felt they assumed Sorcha’s persona while reading the book that I have to believe this tactic worked! I think it gave the story consistency – a single, very distinctive ‘voice’. The simple approach suited Sorcha’s youth and innocence and the fairytale atmosphere of the story.

One major disadvantage of an exclusive first person viewpoint is that it does not allow the writer to add depth to characters by ‘seeing’ them through several sets of eyes. Red, the male protagonist, for example, is a character whose thoughts would enhance the storytelling, but the first person viewpoint means I have to show what he’s thinking entirely through his actions and words. I added another hurdle for myself by making Sorcha mute for most of the story, so while Red can speak to her, she cannot speak to him except by gestures. I did allow Sorcha a form of psychic communication with some of her brothers. That proved extremely useful, as did the gift of scrying which I used for the same purpose in the sequel, Son of the Shadows. But a writer needs to be careful not to overuse such devices.

Another big disadvantage to first person narrative is that it restricts the story to settings in which the first person narrator is present. If that narrator is a young girl like Sorcha, we cannot visit battle scenes or go to her home in Ireland to see how her brothers are doing while she is exiled in Britain, for example. For the more epic stories of my later books, I decided I could not continue to use first person. Also, I wanted to provide more of a balance between male and female protagonists in those novels.

Q: Was it difficult to write the male voice? How does the mindset have to switch?

JM: I did find it difficult to get into the mindset of my first male protagonist, especially as he was a testosterone-fuelled Viking warrior. I did it by reading a lot of Icelandic sagas and by consulting my sons, who had some good insights for me and commented on the ms as I progressed. It is useful to have experts on various topics within the family – one of my sons is an ex-soldier and martial arts exponent. I also have an emergency physician daughter whom I consult on medical matters.

The mindset of the author does need to come as close as possible to that of the protagonist or the novel isn’t convincing, whether or not author and protagonist are of the same gender. Since I couldn’t BE a Viking warrior, I tried to immerse myself in stories of that culture before and during the writing process. I tried to think the way Eyvind would think and base his decisions on his heredity and culture, which included not just the warrior oath and expectation of excelling and dying in combat, but also a happy family upbringing on the farm.

Q: Though there were characters with unique goals in Daughter of the Forest, the book is clearly centered around Sorcha’s quest to save her brothers from a terrible fate. Later books, like Blade of Fortriu and Foxmask, employ multiple quests in the telling of the book. How different are the challenges for you as a writer in crafting a book that revolves around a single quest versus one that splits time between many?

JM: The challenge for me is ensuring I maintain relevance between the various threads in the book. There has to be good reason for telling a tale in such a complex way, and I think that reason, as well as to entertain the reader and make him or her think, is to communicate some core wisdom or theme. There is quite a bit of symbolism in my stories, and I do try to link the different threads in the book thematically. Generally every part of the book will be related to the main ‘learning’ of the book. For instance, while Foxmask is, on the surface, a mystical adventure story, it is really about relationships between fathers and sons – that theme permeates the book. In Blade of Fortriu, the journey of Faolan and Ana tells as a lot about love, loyalty and sacrifice, and the grand war story contains the same themes on a bigger scale.

Q: One of the things I love about Daughter of the Forest is the way you handled the end of the book—Sorcha’s eventual healing, the half-broken relationships in her life and her fragile hope for the future. The bittersweet aftermath seems to be your favored one. What do you gain by avoiding a “blissfully happy ending” with your stories?

JM: Realism, I think, despite the magical elements of the story. I am always aware that in real life, happy endings are generally not happy for everyone and that they often don’t last forever. Some readers find that hard to swallow – they feel that once characters have gone through terrible challenges to reach a goal they should not thereafter have bad things happen to them. But life can be quite arbitrary in what it serves up, and it is reasonable for that to be reflected in storytelling. I apply the same rule to my writing as I do when deciding whether I have enjoyed reading something – sad endings are acceptable as long as the story has some note of redemption or hope in it. It is more important to me for my characters to have become wiser and more mature than to be ‘happy ever after’. In general, I am quite kind to them and often true love does win out.

Q: What is the best advice you’ve ever been given as a writer?

JM: Have the courage of your artistic convictions.

Q: What authors and books have influenced you most strongly as a novelist?

JM: Historical novelists such as Dorothy Dunnett, Rose Tremain, Mary Stewart. Shakespeare for his audacious interpretations of history and his sense of sheer drama. There are some mainstream authors whose work I love and from whom I have learned a lot, notably Ian Banks and Jose Saramago. I don’t read a lot of fantasy but I admire Neil Gaiman for his weaving of mythology into quirky and original novels.

Q: What is your favorite craft book (if you have one)?

JM: As mentioned above, a lot of my own processes are intuitive. I can’t cite a book on writing as a favourite, but I should mention Women Who Run with the Wolves by Clarissa Pinkola Estes. It concerns the role of women in folkloric stories and, although it is not a book about writing, it has certainly had a profound influence on the way I think and the way I shape a story. I also loved Touch Magic by Jane Yolen.

Thank you, Juliet Marillier, and best of luck with your thriving career!

Great read. Thanks :)

And when you said hit, you weren’t kidding. The Amazon reviews are glowing.

Marillier’s a wordsmith and a master at unique and epic plotting, S. William. I hope you pick some of her work up to see for yourself. :)

Absolutely wonderful interview (all 3 parts)! Thank you! This is wonderful help as I teach my English students to find their personal writing style. Marillier creates amazing “worlds” and characters that have so many layers of depth.